There’s more than one way for a COVID-19 vaccine to end this pandemic

Effective vaccines prevent individuals from developing disease, but some also stop people transmitting the pathogens that cause them. What role will they have to play in ending the COVID-19 pandemic?

- 18 September 2020

- 4 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Once COVID-19 vaccines are available, what exactly will they do? In the public imagination, the approval of a vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, will spell an end to the pandemic. This may seem a reasonable assumption, given that vaccination has drastically reduced the incidence of so many fatal diseases. But while it’s clear we cannot end this pandemic without COVID-19 vaccines, precisely how that plays out may depend not just on how they prevent disease, but also whether they can prevent transmission too.

While some vaccines protect individuals from disease, others can also curb transmission in the wider population.

Vaccines are one of the most effective tools we have for improving public health, preventing an estimated six million deaths worldwide each year. But while some vaccines protect individuals from disease, others can also curb transmission in the wider population by preventing the underlying pathogens from being passed between individuals.

Many vaccines achieve this, including: the vaccinia vaccine which eradicated smallpox; the yellow fever vaccine, which triggers long-lasting immunity in 99% of vaccinated individuals; and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which not only prevents cervical cancer in women who receive it, but prevents vaccinated individuals from transmitting the virus. In each of these cases, the vaccine triggers production of antibodies which bind to invading viruses and prevent them from entering cells and replicating. If a virus cannot gain a foothold in the body and reproduce, it will not be transmitted to other people. This is called sterilising immunity.

However, not all vaccines work this way. Some, such the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine, prevent people from developing symptoms of the disease and dying from it, but they can still carry the pathogen and transmit it to others. Such vaccines still provide important protection for individuals, but a high proportion of the population must be vaccinated to protect those who can’t or won’t be vaccinated (herd immunity). With COVID-19, such is the desire to halt the pandemic that vaccines are being developed at unprecedented speed. Any vaccine which reduced COVID-19-related deaths and severe illness would be extremely welcome. But would it spell an end to the pandemic?

If a vaccine doesn’t prevent transmission, there remains the possibility that immunised people could unwittingly pass SARS-CoV-2 to those who cannot be vaccinated, or whose immune systems are too weak to generate a protective response. Without high levels of immunisation – a daunting task, especially when initial stocks of vaccine are likely to be limited – such people could remain at high risk.

Have you read?

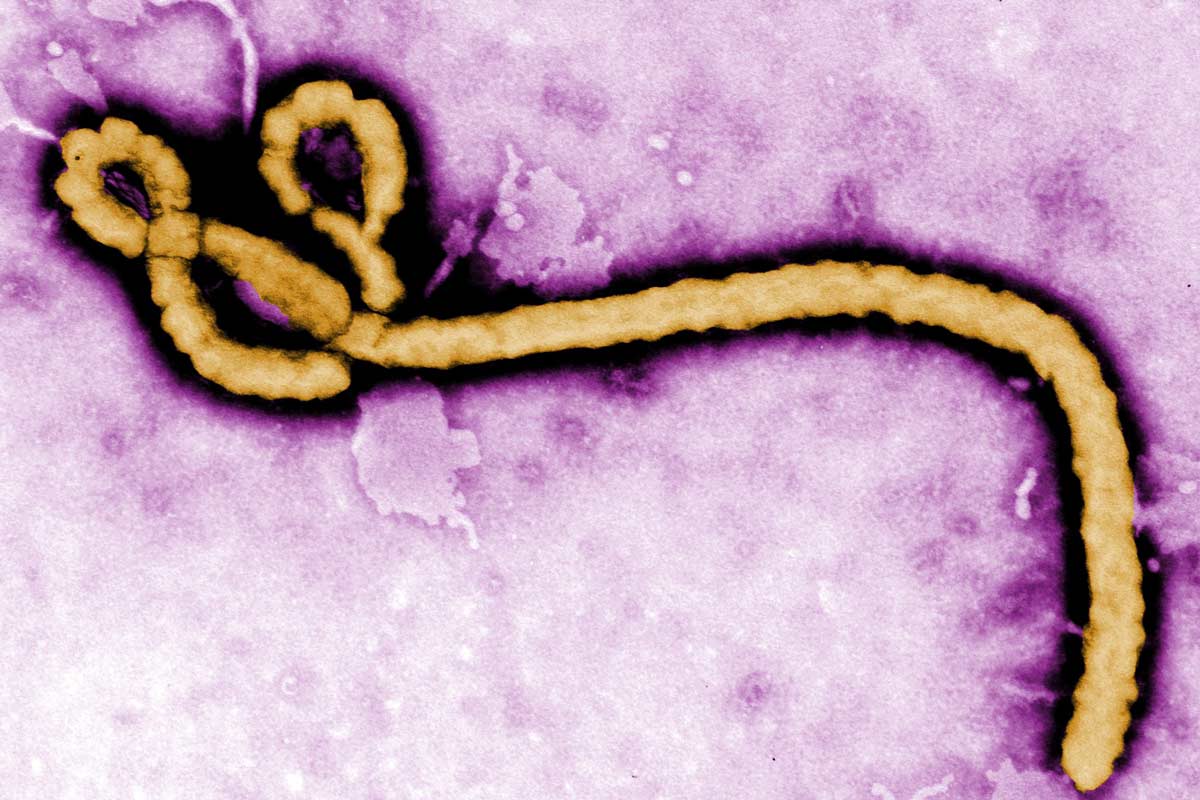

In April, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a document describing what an ideal vaccine against COVID-19 would look like, as well as its vision of a minimally acceptable one. Ideally, any COVID-19 vaccine would achieve at least 70% efficacy – meaning a 70% reduction in the incidence of disease in a vaccinated population, compared to an unvaccinated one – with consistent results in older people and immunity lasting for at least a year. As a bare minimum, any vaccine should achieve 50% efficacy, and protect people for at least six months. As a comparator, the Ebola vaccine used to treat the outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo last year was 97.5% effective.

The WHO document also specified that, as well as assessing whether vaccine trial participants develop COVID-19, and/or the severity of their disease, shedding/transmission should also be considered.

Yet neither governments nor regulators are bound by the WHO’s criteria, and both the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency have indicated that they might approve a COVID-19 vaccine which prevented infections and/or reduced the severity of illness, without proving that it prevented viral shedding or transmission. Already there are hints that some of the COVID-19 vaccines in phase 3 trials may not prevent the virus from replicating in the upper airways, even though they may protect against COVID-related pneumonia.

Given the size of the pandemic, the urgent need for a vaccine and the sheer number of people who stand to benefit from it, such a vaccine would still have massive potential health impact by protecting people from disease. But in the bid to end the pandemic it will be important to explore all vaccine candidates, and ensure that those with a greater potential to protect the wider population do not fall by the wayside. For this reason, some immunologists are calling for vaccine trial participants to be assessed for how abundantly they shed and spread the virus, in addition to how protected they are against COVID-19.

The world urgently needs a vaccine to end the pandemic, but to achieve this, it must protect the many, and not just the few.

We'd love to hear your feedback!

More from Linda Geddes

Recommended for you