The story of measles in five charts

Measles vaccines have had a massive impact on public health, but there’s still a way to go before everyone is protected.

- 6 November 2024

- 3 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Measles-containing vaccines are one of the most effective public health measures going, yet in 2022, some 136,000 people died of measles: a 43% increase on the year before. Measles doesn’t only kill; until recently it was the leading cause of childhood blindness in poor countries. It can also cause hearing loss, neurological disabilities and leave people more vulnerable to other infections.

So, why does measles continue to plague humanity, despite the availability of highly protective vaccines? Here’s our visual guide to the story of measles.

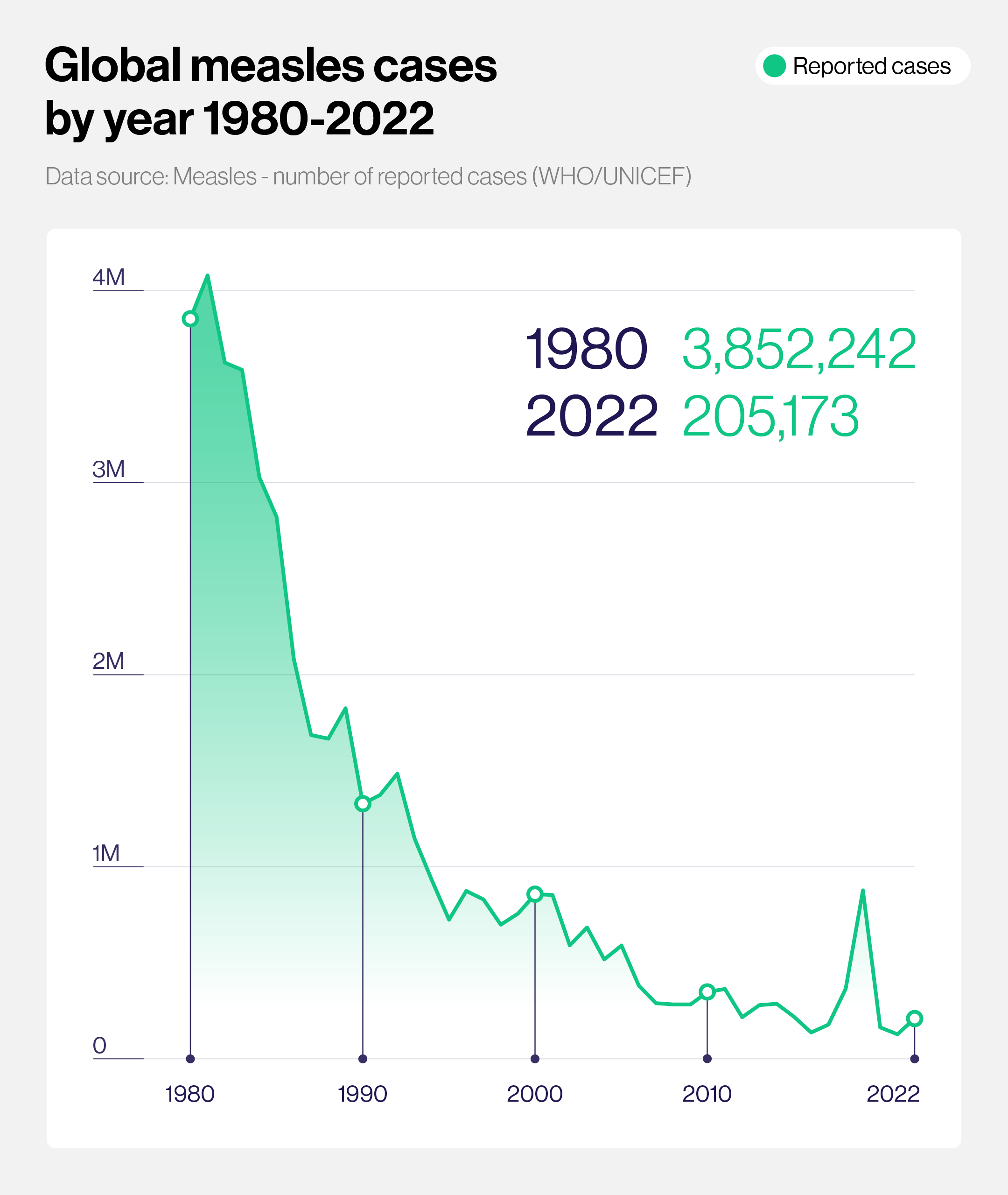

1. Measles vaccines have dramatically reduced the incidence of measles

Before the introduction of measles-containing vaccines in 1963 and mass vaccination against the disease, measles killed more than 2 million people each year. When the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in 1974 to develop and expand vaccination programmes globally, measles was one of the first diseases it targeted. Since then, the world has seen a dramatic reduction in measles cases, from nearly 4 million laboratory-confirmed cases in 1980 to around 205,000 cases in 2022 – although in both cases the true number of infections is estimated to be significantly higher.

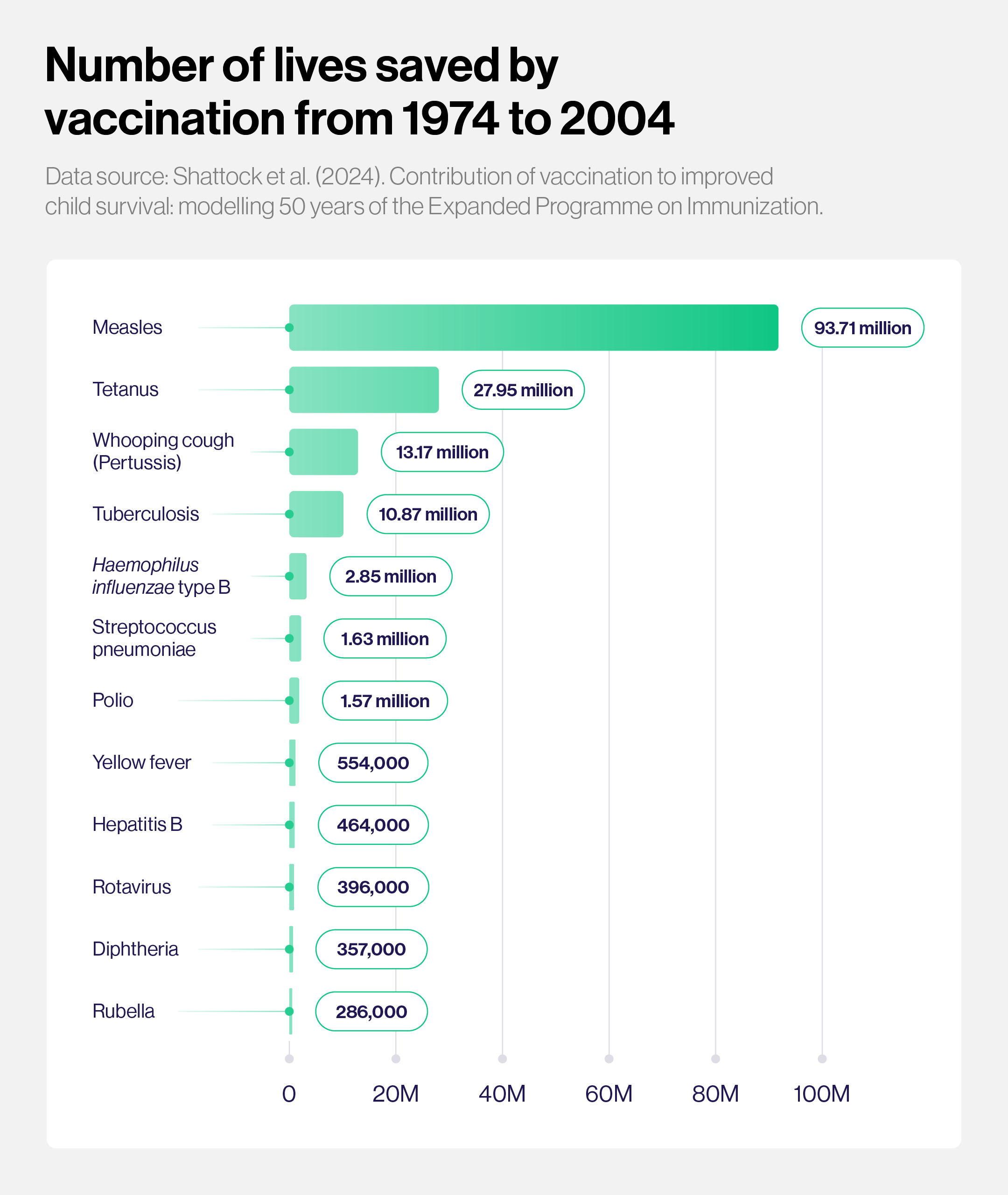

2. 93.7 million lives saved, and counting...

No vaccine has been more effective at reducing the burden of disease and child deaths than measles-containing vaccines. When researchers recently modelled the global and regional public health impact of 50 years of vaccination through the Expanded Programme on Immunization, they estimated that since 1974, vaccination has averted 154 million deaths, with the greatest contribution – 93.7 million lives saved – due to measles vaccination.

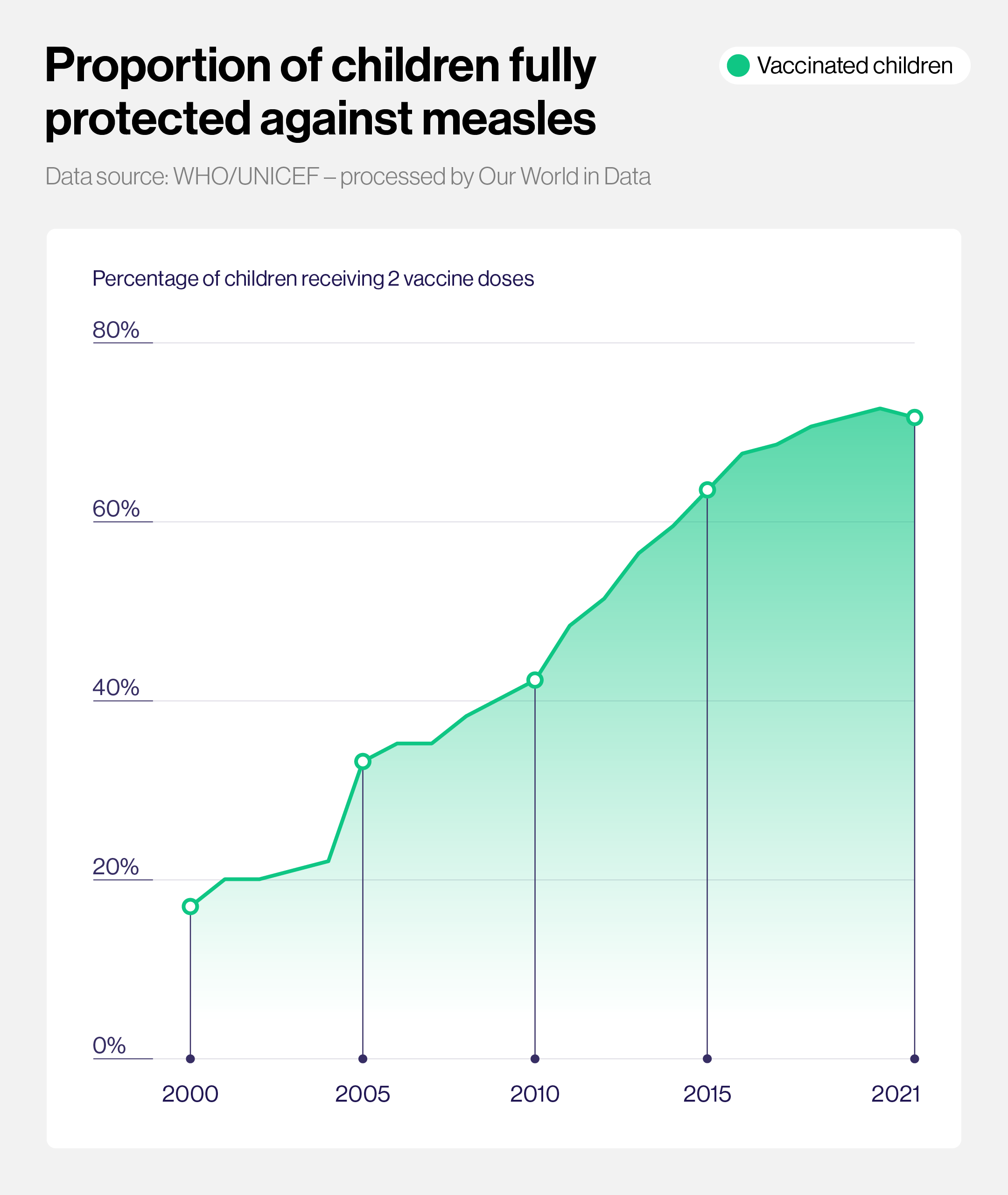

3. But vaccination rates have stagnated, putting lives at risk

Although the proportion of children receiving two doses of measles-containing vaccine has increased substantially since 2000 – the same year Gavi was established – immunisation rates have stagnated in recent years. WHO recommends that children receive two doses of vaccine to be fully protected against measles, but in 2023, only 74% of children globally received both doses (66% in low-income countries).

Although one vaccine dose provides partial protection against measles, the proportion of children receiving this level of coverage has also stalled at 83%, which is 3% below pre-pandemic levels.

To help reverse this trend, in May 2024, Gavi launched its largest ever vaccination catch-up campaign, with the goal of reaching up to 100 million children across 20 African countries.

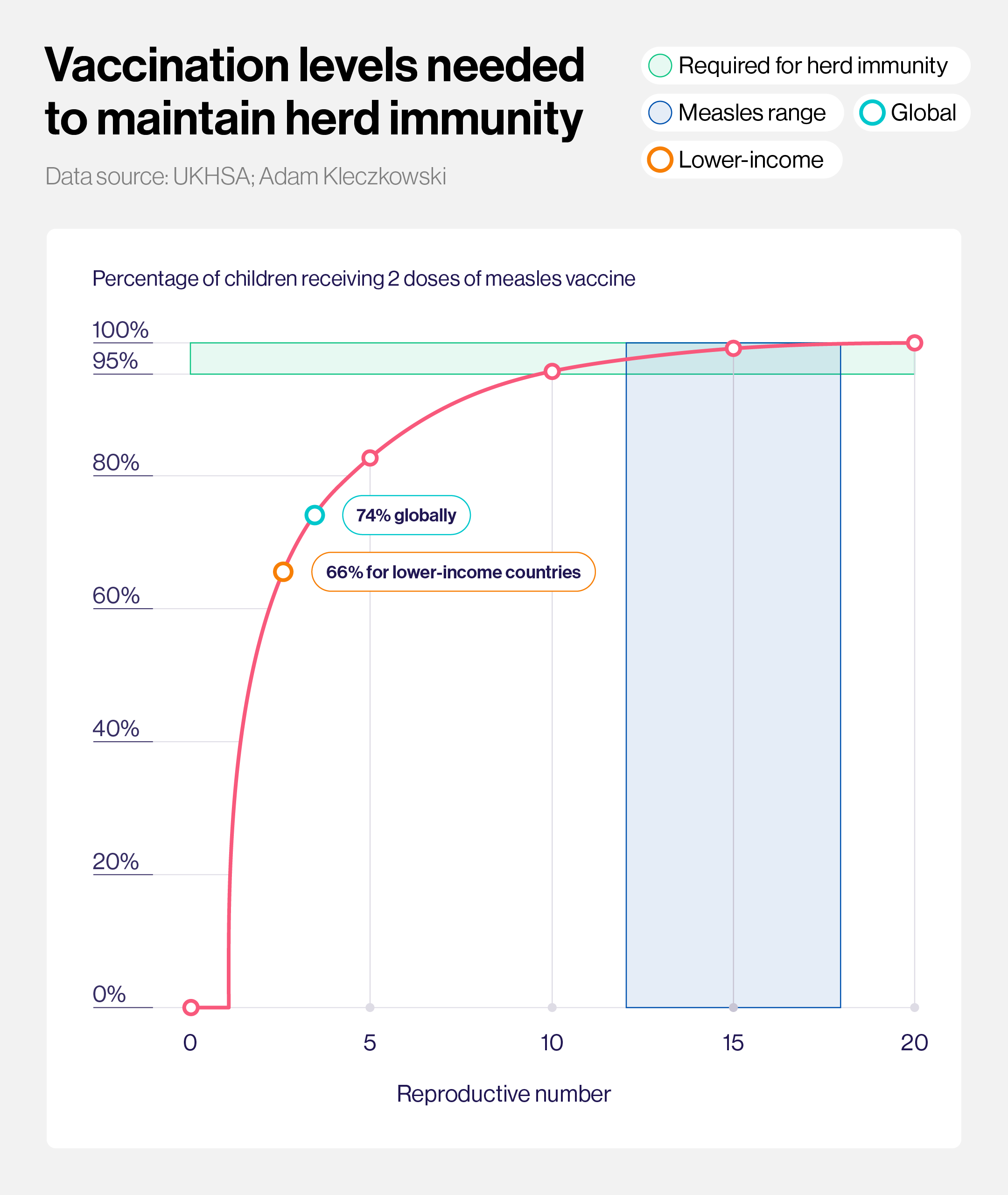

4. Current vaccination rates aren’t high enough to achieve herd immunity

Measles virus is one of the most infectious agents on the planet: one person with measles can infect up to 18 other people. This means that a very large proportion of the population needs to be vaccinated against measles to achieve herd immunity – where even those who can’t be vaccinated, or don’t fully respond to the vaccine, are protected because the virus can’t find anyone new to infect. Once herd immunity has been established for a while, the virus gradually disappears, which is how the world eventually eradicated smallpox. In the case of measles, 95% of the population needs to be immunised to achieve herd immunity. Below this threshold, outbreaks and preventable deaths will continue to occur, which is why routine immunisation and catch-up campaigns are so important.

Have you read?

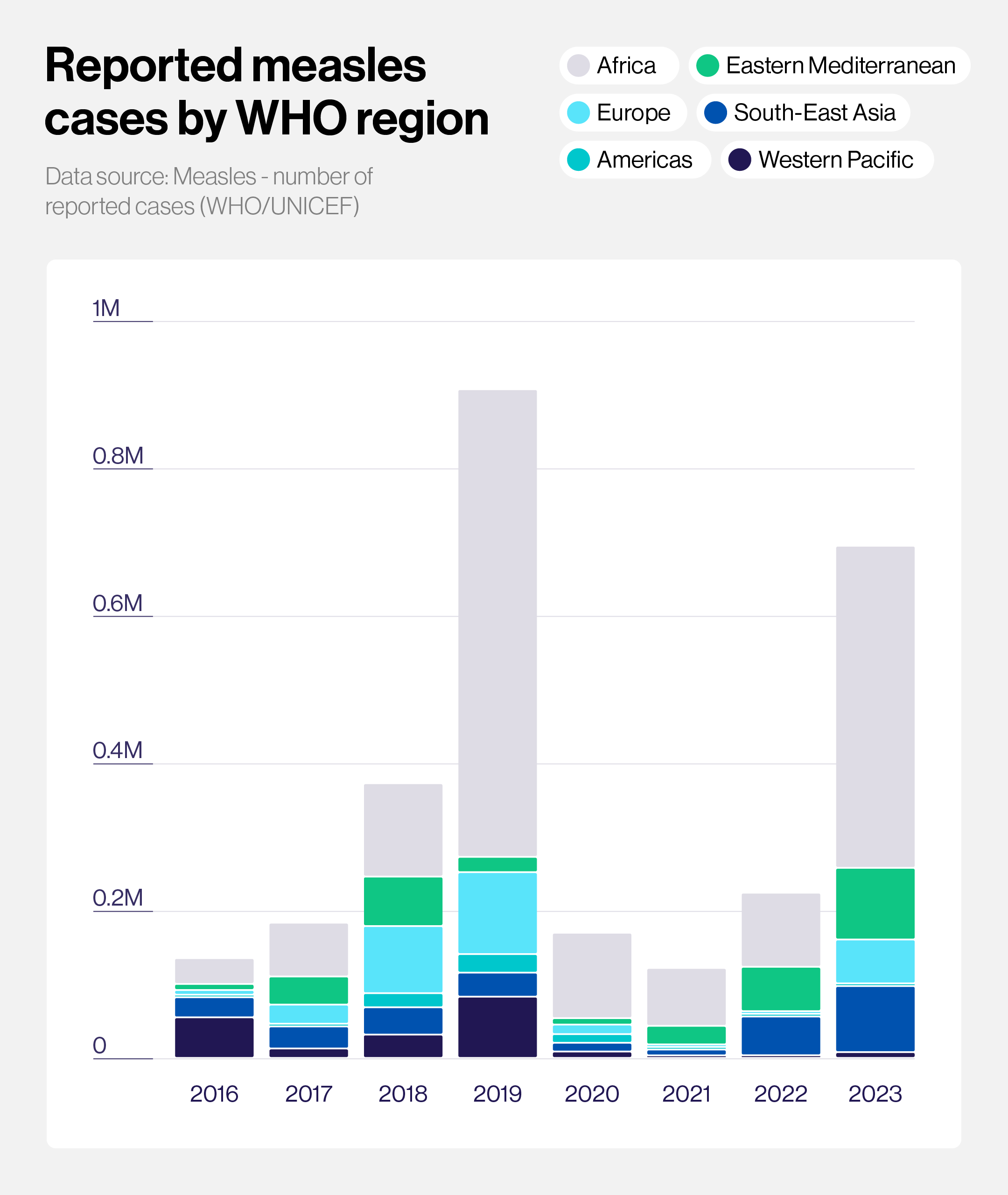

5. Without sustained high vaccination coverage measles will stage a comeback

Measles is preventable through vaccination, but stagnating vaccination rates in many countries led to a resurgence of measles in 2018–19, and a similar pattern is now being seen again. Outbreaks are even being reported in countries where measles had previously been declared eliminated, including many European countries. This is because without sustained high levels of vaccination, an infection can be imported from abroad, and quickly spread – particularly if there are certain regions or communities with lower rates of routine childhood immunisation. The elimination of measles is possible, but it will require ongoing high levels of routine childhood immunisation everywhere.