Six ways to know the COVID-19 pandemic is over

It’s been over a year now since the pandemic first started, and now that vaccines are rolling out in many countries, how long do we have to wait for things to go back to ‘normal’?

- 10 June 2021

- 6 min read

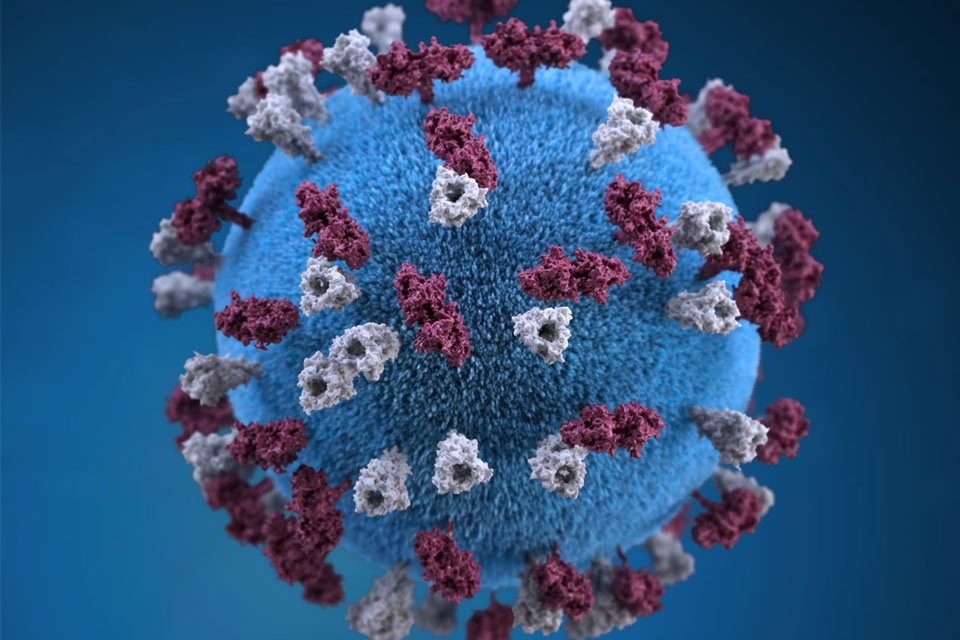

For over a year now, we’ve watched the death toll from COVID-19 march ever upwards. Even when patients survive, their bodies can be affected through conditions like Long COVID months after they were infected. Public health measures such as social distancing, face masks and hand sanitiser are part of our daily lexicon. New variants of the virus have emerged, and vaccines have been rolled out at a record speed. But when will it all be over, and how can we tell when it is?

But while children and adolescents are still largely unvaccinated, and as new variants emerge, the fact that most of us still need to wear a mask a lot of the time indicates that we aren’t out of danger yet.

1. When every country is rolling out COVID-19 vaccines

Vaccines are one of the key ways to end the acute phase of the pandemic. For everyone to acquire immunity to the virus would require either immunisation or for people to develop immunity through infection, but the latter comes at a huge cost to human health. But while wealthy countries are rolling out vaccines as soon as they come in and a third of people in the richest countries have now had their first dose, a fraction of people in lower-income countries have received any so far. For a country to prioritise vaccinating its own people is understandable, but even with border closures and reduced global travel, the world is still highly interconnected – the way variants have hopped from one side of the world to another is proof of this. Thus, ensuring equitable access to vaccines is in everyone’s best interests. COVAX is a global initiative to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, under the leadership of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the World Health Organization, working with delivery partner UNICEF. Although it has so far delivered more than 80 million doses, with billions more to come, it is calling on wealthy countries to share doses or to allow COVAX priority in the queue for vaccines to overcome short-term supply issues. Ensuring every country has access to vaccines could well be one of our best routes out of the acute phase of the pandemic.

2. If COVID-19 becomes endemic

Although vaccines are critical in limiting infections and loss of life, previous pandemics did not die out because of mass vaccination, but because two things happened – our immune systems became trained to recognise the virus as well as because the viruses didn’t disappear but instead evolved to be less deadly over time. A milder version of H1N1, the flu virus that caused the 1918 pandemic is still in circulation today. Eventually, COVID-19 could be like seasonal influenza or other viruses causing common colds which are endemic but mild, and are typically seasonal in nature. It’s possible the coronavirus transitions to being like influenza, evolving frequently and still able to kill people. However flu is still possible to manage through seasonal vaccination.

3. When we can stop wearing masks

Some countries such as China, Israel and New Zealand have already lifted restrictions on wearing masks as they have brought COVID-19 under control through strict lockdowns, border control measures, robust track and trace programmes and rapid vaccine rollout, in the case of Israel. The US has advised that fully vaccinated people don’t need to wear a mask in most places. But while children and adolescents are still largely unvaccinated, and as new variants emerge, the fact that most of us still need to wear a mask a lot of the time indicates that we aren’t out of danger yet.

4. When the economy recovers

Economies have tanked all over the world and around US$ 5.8 trillion dollars was lost in income last year, with 255 million jobs lost. This is unsurprising since all trade and travel stopped immediately for many months last year, with few countries having gone back to ‘normal’. Lives and livelihoods have been lost in devastatingly high numbers, with some industries unable to function as normal. Just as the pandemic caused the economy to crash, injecting funds into ending the pandemic will also benefit the economy. The International Monetary Fund recommends vaccinating at least 40 percent of the population in all countries by the end of 2021 and at least 60 percent by the first half of 2022, as well as ensuring widespread testing and tracing, maintaining adequate stocks of therapeutics, and enforcing public health measures in places where vaccine coverage is low. They say this will bring a faster end to the pandemic and “could also inject the equivalent of $9 trillion into the global economy by 2025 due to a faster resumption of economic activity.”

Have you read?

The World Bank warns though, that economic recovery won’t be even across the globe, with low- and middle-income economies likely to take much longer to bounce back because of slower vaccination rates and a reduced ability to provide financial help to their populations. In addition, countries that are dependent on travel and tourism are unlikely to recover as fast.

5. When we can go on holiday and travel freely

The era of conferences via zoom may dampen the enthusiasm for the constant, never-ending work travel many industries saw pre-COVID, but many people are keen to start travelling again both for holidays and to see family.

Travel restrictions are starting to lift between many countries, though requirements for testing or quarantine still remain in many places. But many believe that travel is unlikely to return to what it was before the pandemic, and people may be wary of travelling to countries where vaccination rates are low.

6. When the WHO says it is

Although the WHO’s Director-General, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, characterised COVID-19 as a pandemic back in March 2020, there is no formal classification of a ‘pandemic’. Instead, the Director-General can label any health emergency a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’, or PHEIC, as Dr Tedros did for COVID-19 on 30 January 2020. This is a formal classification which gives member states a legal duty to act promptly, and is determined by a committee of experts that provides a recommendation to the Director-General. The WHO can then remove this designation, as former Director-General Margaret Chan did for the West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2016. Back then the emergency committee made the recommendation to remove the designation, according to The Lancet, because “the [Ebola] outbreak is no longer an extraordinary event, there is little risk of international spread, and affected countries have the capacity to rapidly respond to new cases.”

Recommended for you