Nudge theory is making inroads in health care, with mixed results

Social cues designed to nudge patients toward healthier choices don’t always work. Scientists want to know why.

- 28 August 2024

- 14 min read

- by Undark

In the 2008 book “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness,” behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein popularized the idea that subtle social cues can effectively guide people’s decision making without restricting their choices or imposing financial incentives. That concept, inspired by decades of behavioral science research, has come to be known as “nudge theory.” The social cues, or nudges, are often surprisingly simple: offering smaller plates at a buffet to regulate portion sizes; sending a patient a text message reminder to discuss cholesterol medication at an upcoming medical checkup; providing utility customers with weekly report cards that showed how their energy use stacks up against other households in the neighborhood.

The ease and relatively low cost of these interventions, and the seemingly outsize benefits they confer, have made them popular with policymakers. In the years following the publication of Thaler and Sunstein’s book, the U.K., U.S., Australia, Germany, The Netherlands, and Singapore governments all established behavioral insights teams — nudging people to pay taxes on time, limit energy use, reduce waste, and adopt other behaviors thought to benefit the public good. Two nudge units in the U.S. government tested 349 nudges in a span of four years.

Although the theory has its critics — detractors argue that nudges can be paternalistic, invasive, ideological, and coercive in ways that erode public trust — many clinicians and public health experts have come to embrace the idea. Some hospitals have created dedicated nudge units to guide clinicians’ and patients’ decision-making — be it encouraging physicians to scale back on unnecessary prescriptions or reminding people to get a flu shot and regularly take medications.

“The return on investment is really large,” said David Tannenbaum, an associate professor at the University of Utah, who studies how people make decisions. “They’re not going to totally fix the problem, but they’re going to be able to move the needle a decent amount.”

“Some of these interventions work, some don’t, and we don’t have a clear understanding of why.”

For Tannenbaum and other experts who seek to use nudge theory to improve health outcomes, the important question is not whether nudges are ideologically good or bad — it’s simply whether they work, and to what extent?

In part because of the speed with which these behavioral science concepts were implemented in real-world experiments, however, those questions have been difficult to answer. Though numerous teams have reported success nudging patients and doctors toward better health decisions, one recent analysis suggests that nudges’ true benefits may be significantly smaller than the academic literature portrays them to be. And some experts argue that the growing interest in nudges is misplaced — that it distracts from larger systemic problems that limit individuals’ ability to make healthy choices even if they wanted to.

Despite a growing data trail to work with, nudge theory’s practitioners are still struggling to tease out patterns that can help them reliably predict when nudges will succeed and fail in real world settings. According to Tannenbaum, it’s important not to overlook the value of nudges, however small. But a pressing mystery in this popular but polarizing field of science, he added, is that “some of these interventions work, some don’t, and we don’t have a clear understanding of why.”

If people always made perfectly rational choices, there might be no need for nudges: Fines, tax breaks, and strict laws might suffice to encourage people to make healthy choices and avoid unhealthy ones. But a core tenet of behavioral science is that humans don’t always act rationally — that people naturally fear losing what they have more than they value acquiring what they don’t; that they tend toward choices that require the least cognitive effort; that they are driven, more often than they care to admit, by social cues.

To some extent, we all desire to fit in, said psychologist Craig Fox of the Anderson School of Management at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Oftentimes people, doctors included, will respond more strongly to social feedback, which is costless, than they will to the financial incentive of a bribe.”

Nudge theory posits that when people think fast or go with their gut, they quickly — seemingly unconsciously — absorb cues from their surroundings and use them as decision-making aids to supplement their slower, conscious choices. Nudges leverage those cues, in ways as subtle as changing the order in which choices are presented on a form or including a note that most people choose a certain option, to coax the reader to do the same. A reminder on a pack of cigarettes that smoking causes lung cancer and harms bystanders could provide the added friction that causes someone to pause before reaching for a cigarette.

Although some of the science underlying nudge theory is viewed as unsettled, nudges have nevertheless gained traction among researchers and clinicians who see them as potentially valuable public health tools. They likely won’t stop a person from skipping an appointment or adding a side of fries to an order, but they make the healthier alternatives slightly easier to choose. “You kind of set people along the garden path towards the desired behavior,” Fox said, “for instance, by making it the default or removing obstacles, making it really easy and simple to behave in the way you’d like.”

Fox and a collaborator, Yale School of Medicine’s Daniella Meeker, were among the earliest researchers to implement nudges in a clinical setting. In a study conducted in 2012, they and several colleagues had physicians from five Los Angeles-area primary care clinics sign a letter stating that they would avoid overprescribing antibiotics, to help limit drug-resistant infections. The researchers then displayed poster-sized copies of the letters in some physicians’ exam rooms. At the start of the experiment, physicians in both groups prescribed antibiotics to a little over 40 percent of their patients. After 12 weeks, that rate had fallen to about 33 percent among doctors who saw patients in rooms with the posters, and it had climbed to over 50 percent for doctors who used the poster-free rooms.

“Oftentimes people, doctors included, will respond more strongly to social feedback, which is costless, than they will to the financial incentive of a bribe.”

Years later, in 2016, the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit became the first behavioral design team embedded in a health care system. The unit’s founders had seen government agencies’ apparent success at applying behavioral science in the public policy realm, and they realized “that there’s no reason why we can’t be doing this in the health care system,” said the group’s current director Kit Delgado.

The unit began inviting hospital clinicians to submit proposals that identified problems they felt could be mitigated with nudges. The team evaluated the proposals based on a suite of factors: How much impact was a nudge likely to have on the problem? How feasible would it be to implement? Would the nudge promote health equity? If a proposal seemed promising, the nudge unit worked with clinicians and other hospital staff to implement it. Over the past several years, the team has completed 46 projects and has four more in the works, Delgado said.

Some of those projects have successfully narrowed socioeconomic disparities in the prescription of cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins, improved the number of statin prescriptions, and curbed prescriptions of opioids. Almost 90 percent of the nudges the team has implemented have shown a statistically significant benefit, according to Delgado.

Delgado said the unit’s most effective nudges are often those that engage clinicians as well as patients, such as a recent effort to boost the number of high-risk patients who get statins. For that project, the researchers tried two nudges at once. The first nudge, aimed at high-risk patients, was a pair of text messages delivered in the run up to a primary care appointment: A text sent four days before the appointment told patients that “at Penn Medicine, it is standard of care to prescribe a statin to patients like you,” and a follow-up message — sent 15 minutes before the appointment — reminded them to speak with their doctor about statins.

The second nudge was aimed at the clinicians: The team modified the hospital-wide digital record keeping system — known as the electronic health record, or EHR — so that when primary care doctors opened the records of a statin-eligible patient, they saw a notice about their statin prescription rates and the drug’s benefits to patients. In a 2022 publication, the team reported that patient nudges boosted prescription rates by 0.9 percentage points, physician nudges boosted rates by 5.5 percentage points, and that both nudges together improved rates by more than 7 percentage points.

“Some of our most successful interventions have been clinician-focused and have been related to making the right thing to do, sort of the easy or default thing. When we do that, it’s often through the electronic health record,” Delgado said. By modifying the system where choices are being made, “you don’t have to go out and prompt people to do things the right way or motivate them,” he added. “It’s just going to happen because you’ve modified the environment.”

Academic journals abound with nudge success stories. But one recent study suggests that nudges may not be as effective as that body of literature portrays them to be. In a 2020 working paper, a team from the University of California, Berkeley, compared results from about two dozen academic studies with data from 126 real-world trials implemented by two major U.S. government nudge units — the U.S. National Science and Technology Council’s Social and Behavioral Sciences Team at the federal level and another that worked across U.S. cities.

In the academic studies, nudges boosted the number of people who opted for the preferred behavior, on average, by 8.7 percentage points relative to control groups who did not receive a nudge. This meant more people, say, picking healthier foods at a buffet, using water treatment methods to reduce diarrheal diseases, or making eco-friendly lifestyle choices. In trials conducted by the governmental nudge units, however, the average effect of a nudge was only 1.4 percentage points.

The Berkeley team concluded that the gap could largely be explained by publication bias: Whereas academic researchers face pressure to publish successful outcomes — and bury the failures — the government studies documented their outcomes irrespective of the results. University of Cambridge psychologist Magda Osman is among several experts who worry that publication bias in academic research has created “a distorted picture of the success of behavioral change interventions.”

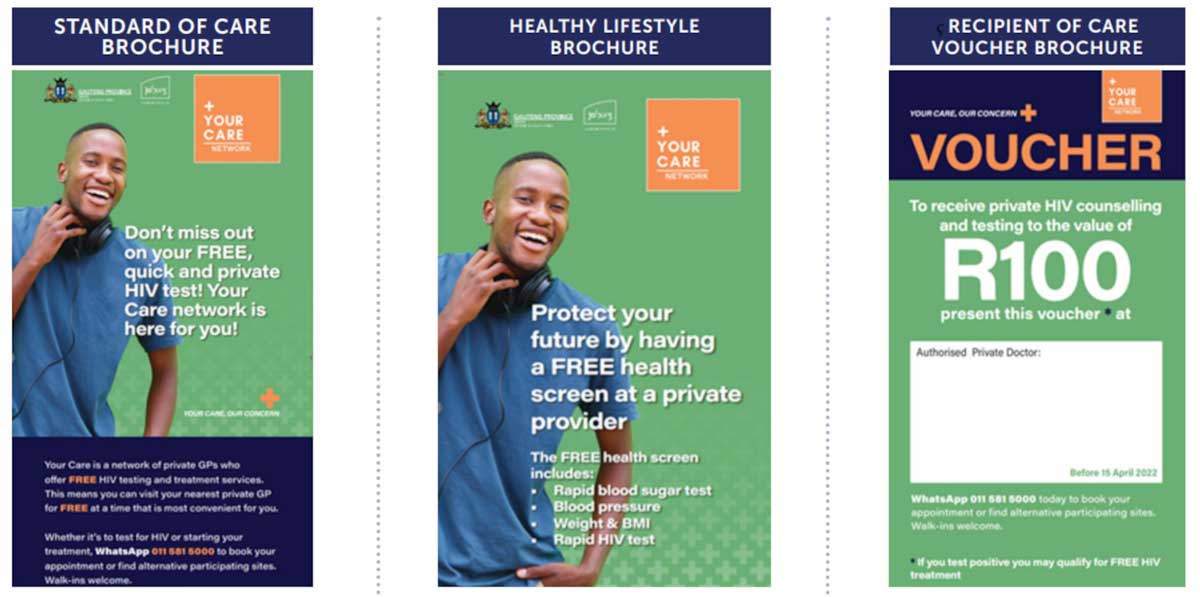

Outside the confines of academia, it can be difficult to predict how even a tried and tested nudge will fare. That’s a lesson University of Pennsylvania economist Harsha Thirumurthy learned when he teamed up with researchers in South Africa in 2020 to launch Indlela, an initiative to apply behavioral science to pressing public health problems in low- and middle-income countries.

One of Thirumurthy’s early projects with Indlela aimed to promote retention in HIV care by improving the text message reminders patients receive for follow-up appointments. Thirumurthy and his colleagues tweaked the language of some of the messages to try to make them more motivating: Some of the new messages urged recipients not to miss out on prescriptions that were waiting at the clinic; others advised patients that taking medicine protected not just their own health but that of their family members.

“We randomized the patients before their appointment to get these different types of messages, hoping that one of the messages might increase the likelihood that the patient actually showed up on time for their appointment,” Thirumurthy said. Indeed, previous studies in the U.S. and Israel had found that tweaking the wording of a text message could reduce the rates of missed appointments. But, in South Africa, Thirumurthy found that the messaging made no difference.

“We hypothesized that it didn’t work in part because the barriers facing patients were different than the ones that the messages were tackling,” Thirumurthy said. If a person simply couldn’t afford transportation to the clinic, he explained, even the most convincingly worded text message wasn’t going to solve that problem.

To Thirumurthy, the outcome revealed how important it is that nudges be “aligned with what is actually going on in the patient’s mind or in the patient’s life.” Strategies that succeed in one country might fail in another, he explained, simply because of differences in people’s individual circumstances or cultural norms.

The factors that can cause a nudge to work in one setting but fail in another aren’t always obvious or easy to disentangle. Yet experts say that understanding why nudges fail will be important for improving future interventions.

Some nudges simply fail to produce an effect, for instance, such as the nutrition labels that were introduced at U.S. fast-food restaurants but made no difference to people’s eating habits, or the information labels at a Dutch online grocery store that did little to change people’s food shopping behaviors. In a 2020 analysis, Cambridge University’s Osman helped introduce a taxonomy of the many different ways that nudges fail. In addition to listing examples of several failed nudges, Osman and her colleagues highlighted nudges that work as intended but trigger negative side effects, or that succeed only temporarily, before their effects are later offset by behavior changes.

“We hypothesized that it didn’t work in part because the barriers facing patients were different than the ones that the messages were tackling.”

There’s some evidence that partisan leanings can influence a nudge’s fate. A 2017 paper by a group including UCLA’s Fox and the University of Utah’s Tannenbaum found that people often conflated their feelings about a nudge with their feeling about the policy it promoted. “If I’m a Republican or conservative-leaning individual and I see an example presented of defaulting people into supporting food stamps, I don’t like it,” Fox said.

In a field where successes often capture the public imagination, Osman and others argue that an open discourse around failure is healthy and necessary. “If we’re going to do something useful, we need to understand why they don’t work,” she said. “But we have to be honest about the fact that they don’t.”

One high-profile case study of a public health nudge gone awry has been unfolding for the better part of a decade in the Netherlands. In late 2016, policymakers there voted to tweak the way people volunteered to donate their organs after death. Decades of evidence from across the world suggested that making organ donor enrollment the default choice — and requiring people to opt-out if they chose not to donate — resulted in higher numbers of potential donors. Lawmakers and public health experts saw it as a potentially effective tactic to address a growing donor shortage: Worldwide, the number of people waiting to receive suitable donor organs grew nearly sixfold over the past 30 years.

The Dutch policy was in many ways a textbook application of behavioral science. But it was also controversial and seen by some as an invasion of personal autonomy. After the policy was approved in 2016, it drew the public’s ire and a groundswell of opposition. The policy change, enacted in 2020, led to about 1 million additional registered donors in the Netherlands, although twice as many explicitly opted out of being listed on the donor registry.

“If we’re going to do something useful, we need to understand why they don’t work. But we have to be honest about the fact that they don’t.”

The ideological battles notwithstanding, it’s not clear that opt-out donor policies have had much impact on national organ donor gaps. In Chile, for instance, some evidence suggests the policy might have backfired, resulting in fewer registered donors on the rolls. A 2019 study of 35 countries found that although the number of living donors is higher in opt-in countries, that didn’t equate to more transplants.

“The actual rates of organ donations hasn’t changed,” said Osman. “It looks like the nudge kind of worked, it worked minimally but not meaningfully.” One possible explanation, Osman and her co-authors suggest in a 2018 study, is that the lines between opt-in and opt-out policies are often blurry in practice. For instance, many countries honor a family’s choice to refuse donation of a loved one’s organs, even if the person was defaulted into a donor registry.

Have you read?

Osman said another underlying issue might be that some countries don’t have enough infrastructure to perform organ retrieval and transplant surgeries in a timely way — regardless of how many people fill the donor rolls.

That assessment speaks to a broader critique that Nick Chater, a behavioral science researcher at Warwick Business School in Coventry, U.K., has levelled against nudge theory. He argues that nudges emphasize individual choices in a way that deflects attention and support away from system-level policies that arguably have more bearing on real-world outcomes. Chater served on the advisory board to the U.K. government’s Behavioral Insights team, one of the world’s first nudge units, in its early years. He recalls that when he joined the team, the potential to solve large public problems using psychological approaches seemed really attractive. But over time, he increasingly felt that “the impacts we could make were often very minimal,” and he argued in a 2022 article that nudges have had a “disappointingly modest” effect.

Encouraging people to use smaller plates to reduce portion sizes or displaying signs about the importance of nutrition makes little to no difference to people’s health, Chater said, because they’re failing to tackle the systemic problem, “which is that we’ve created a food environment in many parts of the world which is just really hostile to healthy eating.” He added, “Trying to help people individually navigate that environment better is not a crazy thing to do, but you’re sort of doing it the hard way.”

As Chater sees it, the challenge of making healthy choices in a world that doesn’t support them is a widespread concern that will make it difficult, if not impossible, for nudges to solve persistent problems in public health and other domains.

“There will always be powerful forces who are benefiting from the status quo,” he said. “They’ll always be saying ‘well, we need to leave it up to the individual but we’ll just try and nudge them in the right direction. But really the forces against people are so great that there’s no real chance that’s going to work.”

More from Undark

Recommended for you