The Kenyan health illustrator explaining vaccination in a universal language

For decades, artist Ben Nyangoma has been painting a safer Kenya into existence.

- 30 September 2025

- 7 min read

- by Pauline Achieng Tom

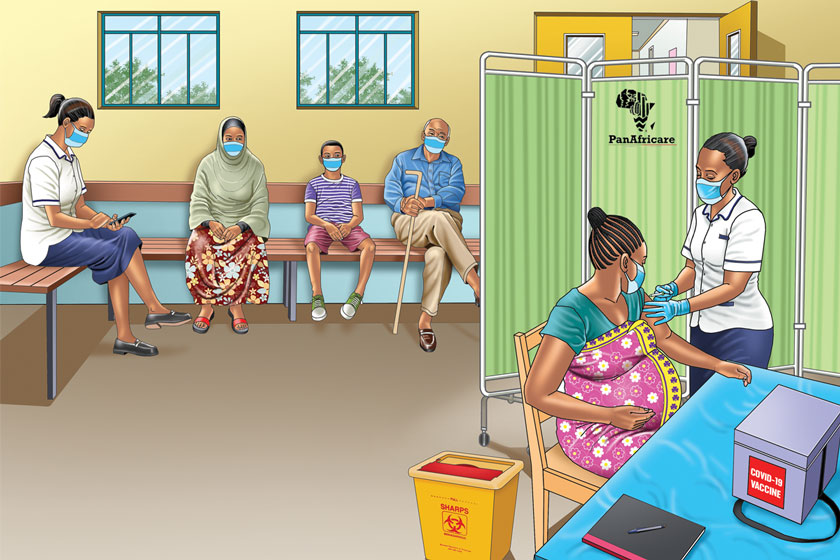

It was a hot afternoon in Gatwekera, Kibra. Grace Odemba walked up to the school gate to pick up her five-year-old daughter, Blessing, when a colourful poster caught her eye. She paused to look: it showed a woman dressed in a kitenge cloth outfit, holding her baby while a health worker administered an injection.

Moments later, Blessing’s teacher handed her a note, which informed her that from Monday onwards, the children would be receiving certain immunisations.

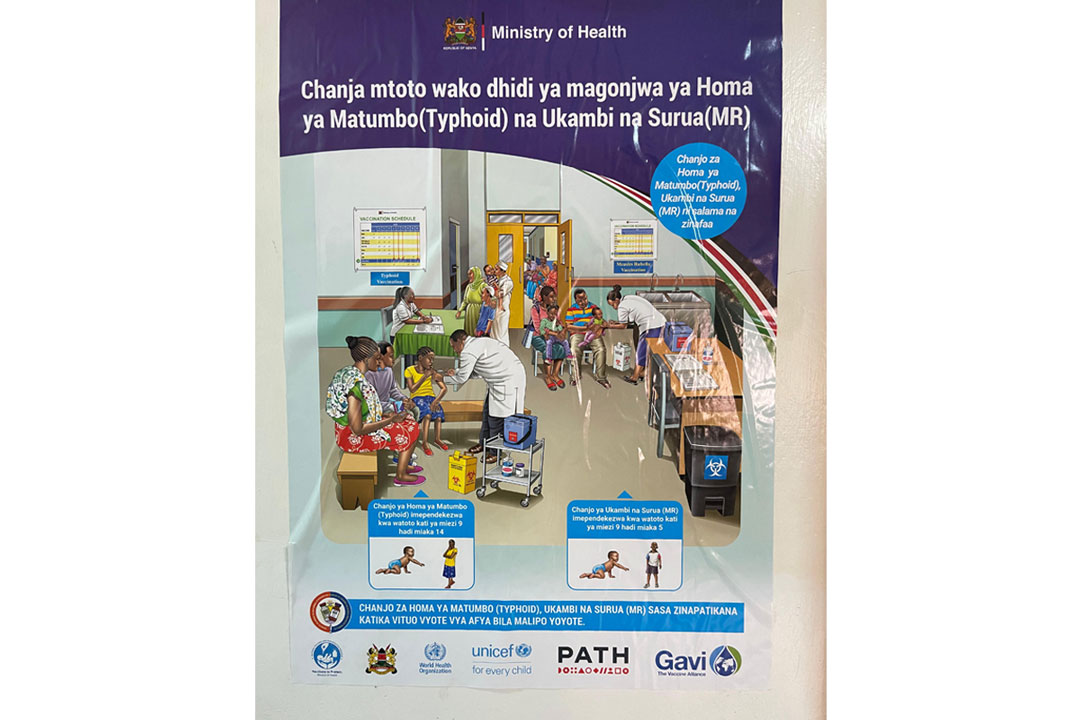

Odemba, who has limited education, could read, but struggled to make sense of the words “Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine” (TCV). She stopped at the poster again and found there was another next to it, depicting people bathing in the water while a child and animals drank from the same water. Beneath it were the words: Vaccinate your child against typhoid, measles and rubella diseases.

This poster hit home for Odemba. Months earlier, she had “almost died” from typhoid. “I was at work when the pain hit and I started vomiting green stuff,” she recalls. “My stomach hurt so bad I couldn’t even stand straight.”

Odemba, who works as a day labourer, depends on her daily wages for survival. “I had to be rushed to the hospital: I lost that day’s wages and more money treating typhoid.”

In Gatwekera, water is often contaminated with sewage, leaving residents exposed to typhoid. According to data from Coalition on Typhoid, incidence in Kibera is as high as 822 cases per 100,000 population, with two- to four-year-old children suffering rates as high as 2,243 cases per 100,000.

For Odemba the poster told the story of their current living situation: she recognised herself in it. “I wouldn’t want my daughter to go through what I did. So when I saw that poster I was ready to get my daughter vaccinated.”

That poster, along with hundreds of others are plastered on walls across the country and around Nairobi’s most vulnerable settlements, are the works of Ben Nyangoma, a health illustrator who is quietly shaping the way Kenyans understand vaccines.

From hobby to health educator

Nyangoma’s journey as an artist started in the 80s. Then in primary school, he found that he had a natural talent for art. “My teachers asked me to draw and write on the board for them, and paid me in porridge,” he recalls, laughing.

Later, he Joined the Royal Technical College – now the Technical University of Kenya (TUK) – where he studied graphic design and communication. He could have gone into a career in advertising, or pursued fine arts. Instead, he found himself drawn to health illustration.

“A friend of mine saw my work, and introduced me to health organisations just after college,” he recalled. “At the time there were big health campaigns including the famous Kick Polio out of Kenya. That is how I started.”

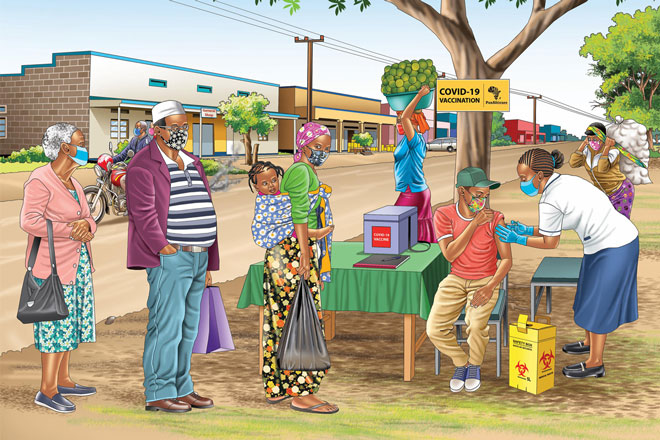

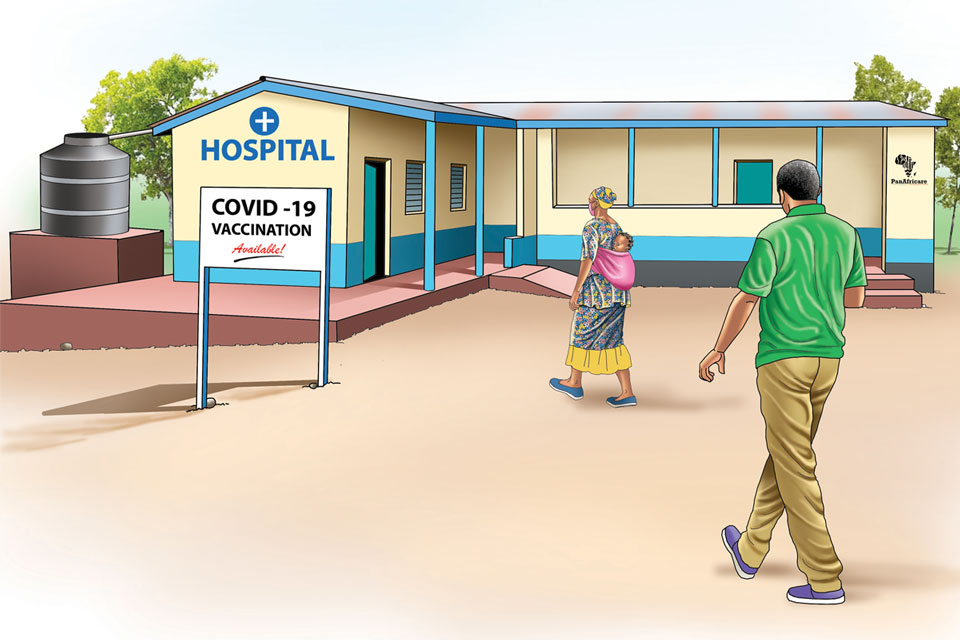

Before embarking on a new illustration, Nyangoma attends workshops with doctors, journalists and policymakers. For him the process is the same whether it’s dealing with novel vaccines like the COVID-19 jab and TCV, or well-known ones like polio. In every case, his task is to break down complex medical advice into images that can be understood by anyone.

“At first it was just drawing, I never imagined people would vaccinate their children because of my posters, but in time I realised that people resonated with the images I drew,” he said. “When people saw illustrations that resembled them, their dressing or environment, they paid attention and acted.”

The art of simple health messages

It’s literally life-saving work. Kenya records 109,000 cases of typhoid annually with 1,607 deaths, according to 2024 data compiled by the Coalition Against Typhoid. The Kenyan Ministry of Health also reported nearly 3,000 measles cases and 18 deaths between January 2024 and February 2025.

These doubled disease burdens prompted a nationwide immunisation campaign in July 2025, which reached more than 16.1 million children aged 9 months to 14 years with TCV – a new vaccine to the Kenyan routine portfolio – and 5.18 million aged 9 months to 59 months with measles-rubella.

Preparations for the campaign started months in advance. Nyangoma reveals that creating a single immunisation poster can take just as long. “Communities bring up things you never even considered. That is why pre-testing is so important.”

Beyond getting to grips with the science, Nyangoma has to be au fait with his variegated audience. Kenya has 47 counties with diverse cultures. For effective communication, relatability is key.

“For Maasai communities, beadwork and shukas (traditional drapes) must be visible. In Somali-targeted campaigns, women in hijabs and men in kaftans are drawn. For Turkana, the landscape must reflect arid brown hues, not green fields. Even for urban Gen Z audiences, fashion and slang shape the illustrations,” he said.

Have you read?

Beyond dressing and environment, Nyangoma also features subtle cues that reflect the African household dynamic. “You will notice that while mothers are usually the dominant figure. In some of the posters, I am careful to include fathers as well.”

He adds, “If a wife takes a child for vaccination without the husband’s knowledge, it can create conflict, so I often include fathers in the background, showing support.”

Why posters work

Even if the visual dialect is adapted to the specific language, in low-resource areas, especially where literacy and vaccine knowledge is limited, posters and cartoons offer a universal language. For Esther Atieno (30), a mother of four from Kibra, posters bridged a consequential communication gap.

“I am good with money, but reading is a problem for me,” she jokes. “But cartoons help me know what is happening. They showed me how typhoid fever is spread and that vaccination is safe, and I wanted my children protected.”

Her words echo what health communicators like Ben Nyangoma have always recognised: simple messages that reassure can cut through fear and confusion.

“People are more likely to act when reassured rather than threatened,” Nyangoma notes, referring to the harsh HIV/AIDS campaign in early 2000s that featured horrifying images. “I consider a softer approach in my illustrations, and the goal is to inspire change, not scare people.”

Pasting up posters

In Kenya, community health workers are essential in any immunisation campaign. In Kibra, Christopher Osuto has covered many immunisation campaigns with his team. Before any vaccines are given they first have to put up posters and illustrations done by Nyangoma – which come to them via the Ministry of Health.

“Before we started distributing the posters, we have a meeting with health officials and other community health workers,” he says. “We map out the areas we are going to cover and identify where these posters will go based on the impact intended.”

He adds, “In the last campaign we identified schools, churches, bus stops, water points and gates to homesteads.”

Osuto confirms the impact of the posters having served Kibra and Dagoretti communities. “When I talk to people about upcoming immunisation drives, they might forget. But when a poster is on their gate or at the water point, they keep seeing it. It reinforces the message. Posters are self-explanatory, and parents immediately understand.”

From COVID-19, polio to the recent TCV-MR vaccination campaigns, Nyangoma’s work has spanned across decades, reaching places and engendering changes that he will never truly fathom. But the signs of impact that he’s seen make him grateful for taking the journey into medical illustration.

“Since childhood, I’ve been passionate about art. Now I get to use it to save lives,” he says.