The HPV vaccine

A VaccinesWork guide: news, science explainers and reported dispatches giving you everything you need to know about the human papillomavirus vaccine and its roll-out.

Why do we need the HPV vaccine?

In 2022, nearly 350,000 women worldwide died of cervical cancer: that’s a life lost every other minute. The overwhelming majority of those women could have been not only saved, but spared from illness, by a single dose of vaccine earlier in their lives.

The vaccine in question directly protects against the human papillomavirus (HPV), an infection so staggeringly common that an estimated 80% of adults will have been exposed to it by age 45. In a majority of cases, that exposure is no big deal, but when infection persists – that is, when the body fails to clear the invading virus – it can spell mortal danger.

Cervical cancer is not the only cancer caused by chronic HPV infection, but it’s the most common. More than 650,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, and an estimated 91% of those cases are traceable to an infection with one of a few vaccine-preventable strains of HPV.

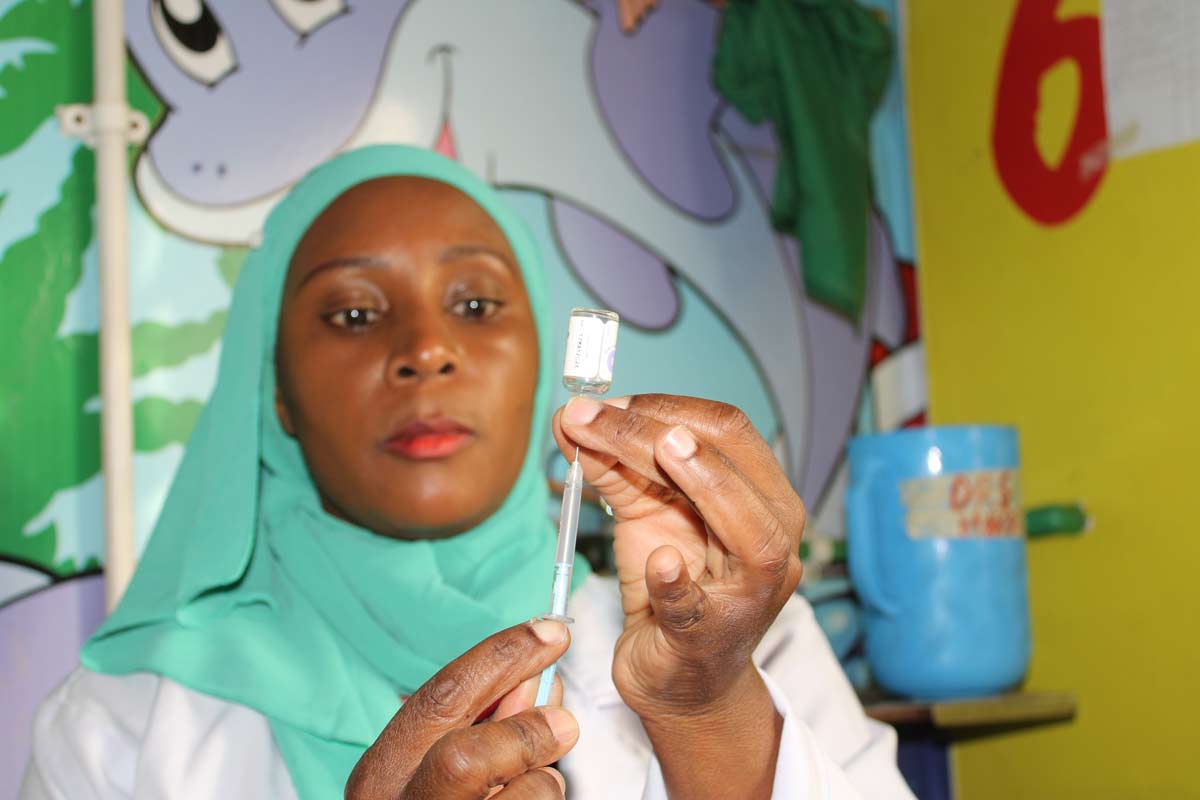

Getting a dose of HPV vaccine to every girl – along with screening and treatment for adult women – would prevent the suffering caused by cervical cancer for millions of women worldwide within a generation.

Immunising just 1,000 girls will save on average 17.4 of them from death by cervical cancer in adulthood. That said, like most diseases, this one is no equitable killer: a woman is far more likely to die of the disease if she is poor. Of the 350,000 women who died of cervical cancer in 2022, more than 90% of them were in low- and middle-income countries, where access to both screening and treatment is harder to come by.

By the end of 2025, with Gavi’s support, 53 of those countries will have national, public HPV vaccination programmes, meaning that girls of all backgrounds can get protected, forever, for free.

Everything you need to know about HPV

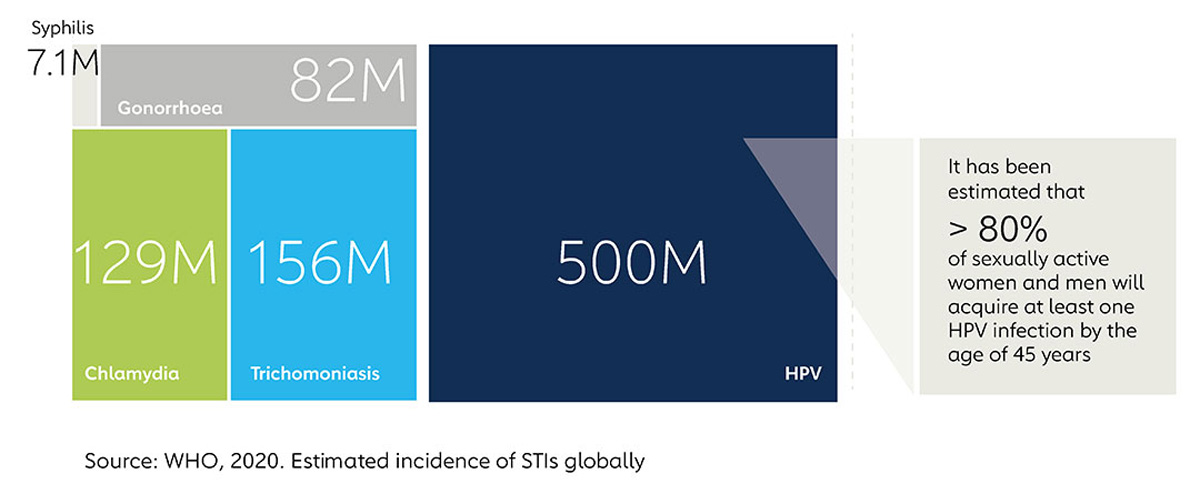

The scale of the problem

80% of sexually active women and men will acquire at least one HPV infection by age 45 – though the virus can be transmitted by non-sexual means too, meaning that even celibate people are at risk of exposure. In nine out of ten of those hundreds of millions of cases, the body clears the infection. But that still leaves tens of millions of chronic HPV infections – tens of millions of people at risk of complications that could include cancer.

Where does cervical cancer hit hardest?

More than 90% of cervical cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, for two principal reasons: firstly, screening (think pap smears and HPV tests) and treatment are far more readily available in rich countries. Secondly, the HPV vaccine has been offered for longer in high-income countries – but Gavi's working on balancing that out.