How Kosovo led the way in protecting girls against cervical cancer

In less than a year, Kosovo has vaccinated three-quarters of all sixth-grade girls against HPV, the virus that causes cervical and other cancers. Here’s how it did it – and what other public health authorities can learn.

- 6 November 2024

- 6 min read

- by UNICEF

Amara, a vivacious twelve-year-old from Prishtina, Kosovo, bubbles over with enthusiasm when you ask her about math, ballet, volleyball – and about the HPV vaccine.

This spring, Amara was the first in her class to get the vaccine. She had "no worries" about accepting it, she says. It helped that her parents, both doctors, understood both the vaccine's safety and why it is so important. The nurses who came to her school to administer it also allayed any concerns.

"They told us that it protects us from disease, and keeps us healthy," she says. "So I wasn't stressed."

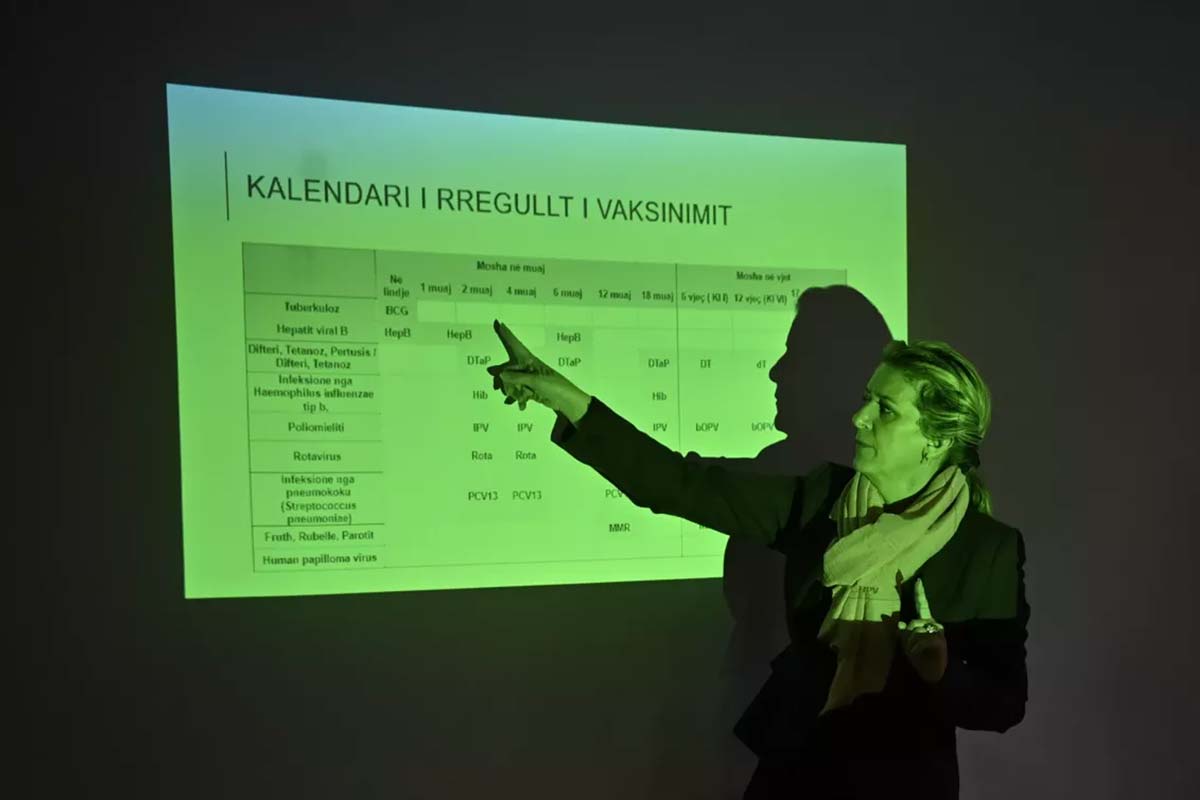

Before 2023, the HPV vaccine wasn't on Kosovo's universal vaccination schedule. As a result, only a "very small" number of children were vaccinated against HPV, says Dr. Fetije Fetaj, epidemiologist specialist and chief of immunization at the National Institute of Public Health in Kosovo.

But since a full-scale vaccination campaign began in February 2024, more than 9,000 girls have received the HPV vaccine. That is a full three-quarters – 75 per cent – of all sixth-grade girls in Kosovo. The number far outstrips many of Kosovo's neighbours; across the European region, only 40 per cent of girls have received one dose of the HPV vaccination by the time they turn 15.

This is also a number that could be life-saving. Available since 2006, the HPV vaccine is extremely safe, effective – and one of the few vaccinations that prevents cancer. This is because HPV causes around 5 per cent of all cancers worldwide. These include cervical cancer, but also anal, vulvar, penile, oropharyngeal, and vaginal cancers.

For example, around 95 per cent of all cervical cancers are caused by HPV infection. The fourth most common cancer for women worldwide, cervical cancer kills 350,000 women every year. Given the vaccine's more than 90 per cent efficacy, if each of these women had received an HPV vaccine, some 300,000 lives every year would be saved.

In Kosovo, the prevalence of women having cancer of the reproductive organs has been on the rise – from 73 cases in 2012, quintupled to 361 in 2021, says Dr. Fetaj.

"For Kosovo, the HPV vaccine is expected to greatly reduce cervical cancer cases," she says. "Research conducted in other countries that have already introduced this vaccine has shown a decrease [...of cases]."

Kosovo's efforts to protect its citizens from cancer – as well as the other less-lethal, but also unpleasant, symptoms of different HPV strains, such as genital warts – have sprawled across local, national and international organizations. The National Institute of Public Health in Kosovo, with support from UNICEF and the World Health Organization in partnership with GAVI, provided training on the vaccination and communication for HPV vaccination to medical workers, including outreach to vulnerable communities. Health workers coordinated with the Ministry of Education to distribute brochures in schools and speak with teachers, who often field questions from parents, about the importance of the HPV vaccine.

On 20 February 2024, the vaccination campaign began. Doctors and nurses then went into schools to offer the vaccinations on the spot. The first priority has been vaccinating sixth-grade girls, like Amara and her friends.

Of course, there were challenges. Dr. Rejhane Zhushi Musliu, chief of immunization in the municipality of Obiliq, recalls that at one school, a mother didn't want her daughter to receive the vaccine. When health professionals came to administer it, not only did her daughter refuse – but so did the other sixth-graders. "None of the girls in that class took the vaccine," Dr. Musliu says.

Rather than give up, Dr. Musliu and her team persisted. They arranged discussions with the director of health, and with the mayor – who both spoke to the mother themselves. They listened to her concerns, and then shared the evidence about the vaccine's safety and its lifesaving potential.

"They informed the mother about the consequences of HPV, and about how lucky the girls are, at their age, to get the vaccine," Dr. Musliu says. "In two days, we managed to change the mind of all of these parents."

When health workers returned to the class, every single girl agreed to get the vaccine.

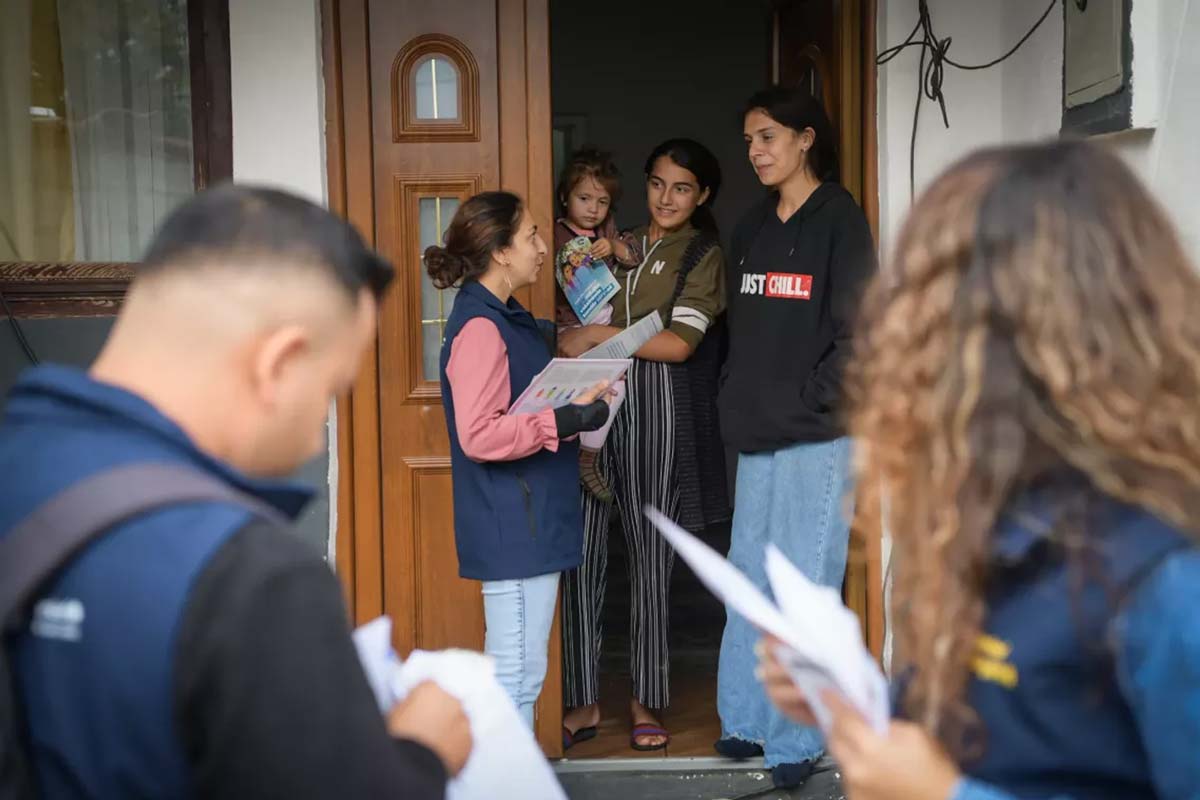

Other obstacles have been in reaching adolescent girls who may not be attending school regularly, such as those from non-majority communities. Nuhi Morina is a supervisor at the social advocacy group Balkan Sunflowers Kosova, which enlists volunteers to provide a variety of services to families from Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities, including awareness raising activities for immunization.

The volunteers are used to going door-to-door to raise awareness about vaccinations. The HPV vaccine, however, required its own approach. One misperception the volunteers had to dispel, for example, was that the vaccine was new.

"People thought that this is a new vaccine. It's not new – it's new to us," he says.

To reach parents, Morina and the other volunteers held information sessions with the parents. Then they went from household to household, speaking to families and determining how many children there are, how old they are, which vaccines they've received from the routine vaccine schedule. They often worked on weekends, when children were more likely to be home.

Discussing HPV, a sexually transmitted disease, can be especially taboo. "Girls often hesitate to talk even with their mothers about these issues," he says. "Even when they get their first menstrual cycle, they don't feel comfortable sharing. But they feel more free to talk with their friends and peers." As a result, the volunteers also hold HPV information sessions where they divide participants out – not just by gender, but age. Mothers will be in one group; adolescent girls in another.

For the same reason, he says, he splits responsibilities with the female volunteer he works with. If they go to a home and the father is there, he might speak with the father. But it is the female volunteers that will speak with the mother and girls.

As they went door-to-door, the volunteers also identified the case of a girl who was having cervical cancer-like symptoms. They connected her family with the hospital. But it worried them.

"This made us a bit afraid, so we are intensifying our efforts to promote the vaccine even more in the community," he says. "Considering that now it's being given for free, we don't want to let a [Roma, Ashkali or Egyptian] girl not have this vaccine – we want them to have this protection."

Next steps, says Dr. Fetaj, include expanding the age group of eligible girls, as well as including boys – who also carry, transmit and suffer from the consequences of HPV, such as with anal and penile cancers.

Dr. Fetaj also wants to see more attention paid to making sure that cervical cancer screenings, also referred to as 'Pap tests', are both routine and accessible to all women. "Routine visits for women in Kosovo are not as well-developed or systematic, and it can take a long time before a Pap test is done," she says. "Vaccination alone cannot make miracles, but when combined with regular check-ups, it could have a major impact on public health, particularly women’s health."