How geospatial technology is helping Nigeria’s COVID-19 vaccine roll-out

In a huge country like Nigeria, ensuring the right people receive COVAX vaccines is not just a question of how, but where. Could geospatial technology, trialled during previous polio campaigns, make a difference?

- 8 April 2021

- 3 min read

- by Adejoke Oguntade-Adeboyejo

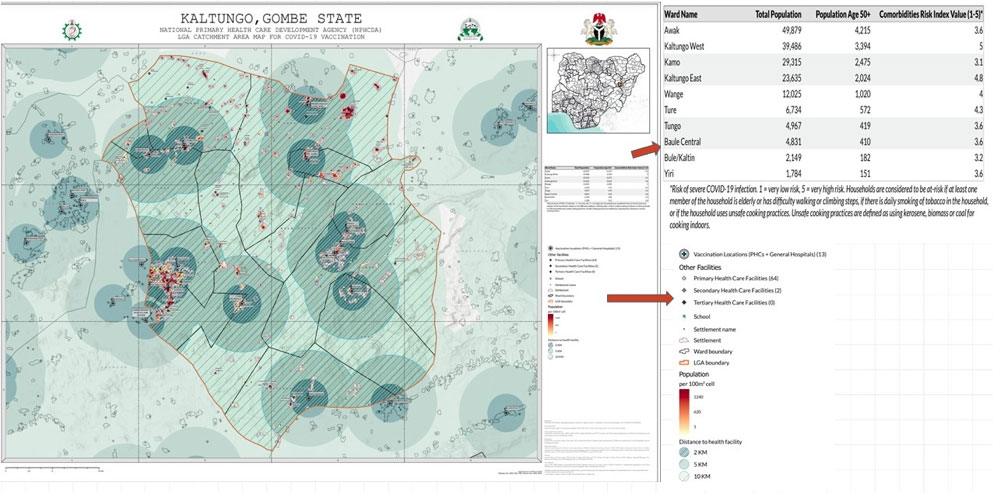

In the lead up to Nigeria receiving the first batch of 16 million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine under the COVAX initiative, one area of concern was how to distribute the vaccines across the country’s vast 923 square kilometres land mass. This is where geospatial technology solutions provided by GRID3 (Geo-Referenced Infrastructure and Demographic Data for Development), managed by the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) at Columbia University, comes to the fore.

Registration for vaccination is done on the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) website and the process prioritises frontline healthcare workers, those who work in contact tracing teams and vaccination teams.

Nazir Halliru, Nigeria Project Consultant for GRID3, explains: “The maps are used by the health care workers at the local government level for micro planning. This will ensure all geographic areas, settlements and target groups that should be covered by the vaccination teams are reached.”

Fortunately, Nigeria has experience with the technology following their use in previous vaccination and immunisation programmes. It was especially instrumental in aiding efforts to eradicate wild polio. For many years, Nigeria faced huge challenges when it came to polio eradication, experiencing regular spikes in cases even when the battle seemed to be close to being won. At some stage, it was even thought that local conflict and negative perceptions of Western medicine were key causes of the spike. And then, one day, a team of health workers visiting settlements in Northern Nigeria discovered that the hand-drawn maps they had did not match what was on ground. Integration of geospatial data into vaccination planning processes proved to be the game changer.

“One of the ways the maps assist health workers is that they accurately show potential vaccination sites, such as hospitals and health centres,” Halliru says. “The maps also indicate population estimates, settlements and other infrastructure.”

With the aid of the maps, the vaccination rollout has been scheduled in phases that make the exercise more effective.

Have you read?

“For the current vaccination phase, the maps are developed to help in estimating the vaccine requirements by ward, based on the granularity of the population estimates,” explains Halliru, who has worked in the space of Data Application in Public Health for more than eight years.

“For subsequent phases, the GIS [geographic information systems] maps will determine additional vaccination sites based on the population density, areas for a temporary fixed posts where vaccine demand will be low, and areas or wards with highest comorbidity risks”.

Halliru also says that, to handle the maps effectively, the health workers have undergone the necessary training.

“At the national, state and local government levels, training was provided for health workers as part of the COVID-19 vaccination introduction training by NPHCDA" he says, referring to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency. "An additional specialised session will be needed specifically on the use of the maps."

The Nigerian Government has plans to vaccinate 40% of the population by the end of 2021. Registration for vaccination is done on the NPHCDA website and the process prioritises frontline health care workers, those who work in contact tracing teams and vaccination teams. Others include security personnel, teachers and the older people, especially those with co-morbidities such as diabetes, HIV, cancer and other immuno-compromised patients.

More from Adejoke Oguntade-Adeboyejo

Recommended for you