How deradicalisation programmes are helping former Boko Haram captives find their way back

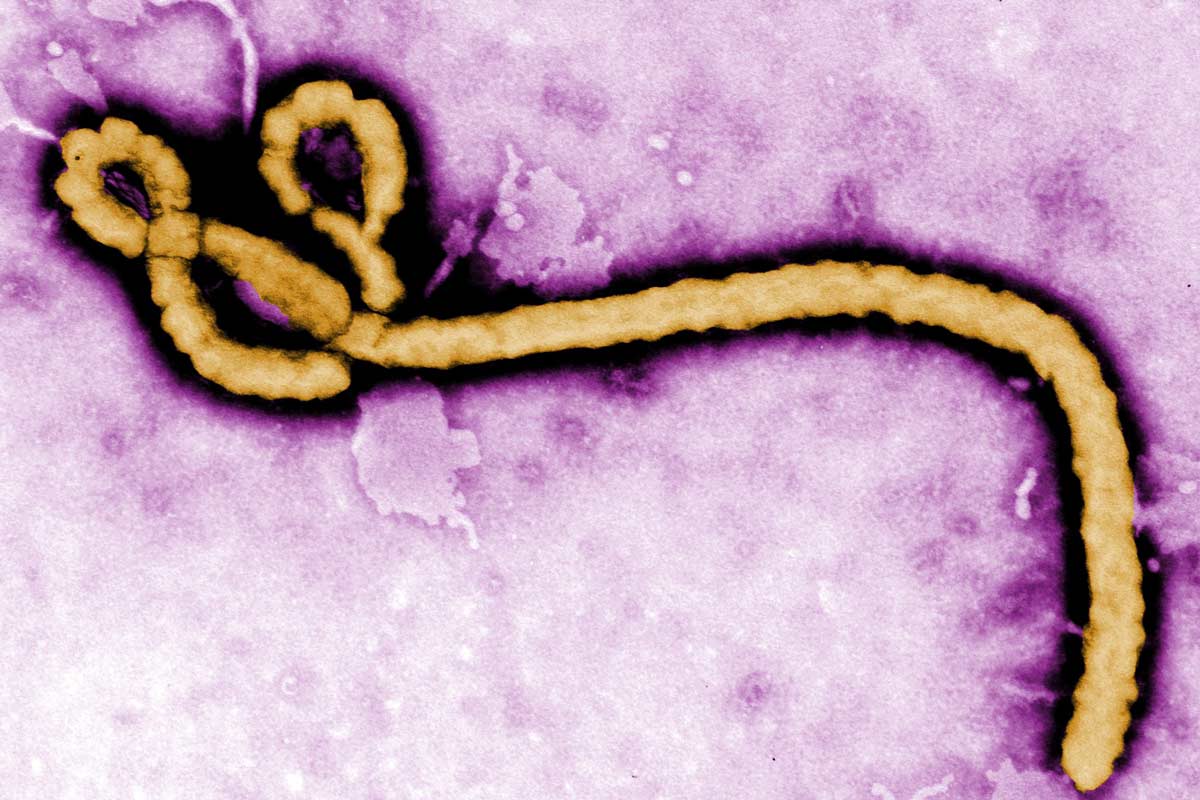

Reintegration is a multifaceted process. For many former captives, it includes unlearning the extremists’ lesson that childhood immunisation is sinful.

- 11 September 2023

- 9 min read

- by Jesusegun Alagbe

For the past five years, John Ochojila has journeyed from one internally displaced persons camp to another, and from one community to another in Borno State, northeast Nigeria, offering counselling sessions to people who regained their freedom from Boko Haram, the jihadi group that has terrorised the region for over a decade.

Ochojila – a clinical psychologist specialising in deradicalisation, who works with the nonprofit Save Sanity Foundation International – said that to date, he has counselled more than 100 formerly captive people. Most of them have been women, and his job has been to help them process their trauma and move away from the extreme views they were subjected to under Boko Haram.

There were people among the kidnappers whose job it was to brainwash the captives into believing that mainstream education and routine immunisation for children were haram (sinful) in Islam.

"We have been carrying out deradicalisation sessions, trying to reintegrate mothers and people previously held captive by Boko Haram into their communities," Ochojila said. "They all had different ways in which they were indoctrinated."

Stolen bodies, stolen minds

Some of the women were kidnapped and forced to become wives of Boko Haram commanders, living as sex slaves for years, Ochojila explains. Those who resisted risked being battered or killed. While in captivity, many of the women, as well as other captives, were reportedly introduced to psychoactive substances.

There were people among the kidnappers whose job it was to brainwash the captives into believing that mainstream education and routine immunisation for children were haram (sinful) in Islam.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

According to the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank, for the past 13 years, the Boko Haram insurgency in northeast Nigeria has displaced 4.5 million people, particularly in Borno State, the epicentre of the insurgency. The organisation notes that the Boko Haram uprising upended the lives of thousands of women and girls, who are the "overwhelming majority" of the North East's 1.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs).

"Apart from the deradicalisation sessions, what has also worked with respect to mothers taking their children for routine immunisation is the provision of incentives, like food."

– John Ochojila, clinical psychologist

But military attacks on the terrorists have led to the arrest of many fighters and the rescue of captives. With the assistance of local and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), United Nations agencies, federal authorities, and donor governments, the Borno State Government has sheltered hundreds of thousands in camps.

Re-entry

Camps like these, as well as in informal settlements, is where Ochojila does his work. Many of his patients have since successfully reintegrated into society, and that has frequently involved getting their unimmunised children up-to-date on their protective jabs.

"Apart from the deradicalisation sessions, what has also worked with respect to mothers taking their children for routine immunisation is the provision of incentives, like food. I am aware the World Health Organization (WHO) is doing great work in this regard in the communities," Ochojila said.

"Boko Haram would order you not to vaccinate your children because it is haram, citing some religious injunctions. But now I know they told us lies. Health workers often tell us about the importance of giving our children routine vaccination. All my four children take these vaccinations whenever the opportunity presents itself and they are all healthy."

– Fanna Garba, mother of four and former Boko Haram captive

Now many of Borno's displaced people are being made to move on again. Between 2021 and December 2022, Borno State authorities shut down many IDP camps across the state, asking displaced persons to return to resettle their reopened communities.

Local media reported that the governor, Babagana Zulum, argued that the camps did not allow for economic and social development, suggesting that they were becoming slums, where all kinds of vices were happening, including prostitution, drug abuse and thuggery. The camps' closure has reportedly resulted in the relocation of about 200,000 people to rural communities.

Through her NGO, the Women in the New Nigeria and Youth Empowerment Initiative (WINN), Lucy Dlama takes deradicalisation tours to these resettled communities.

"We carry out several sensitisation tours, going to the communities and helping to reintegrate freed captives, and even repentant Boko Haram terrorists, to society," said the activist.

"We visit places like Gwoza, Dikwa, Mafa and Konduga. We work with the local authorities. We involve psychologists and nurses to care for these people and provide vocational training like tailoring, hairdressing and cosmetic making so they can have something to do," Dlama stated.

Survivors remember

Thankfully, the work of people like Ochojila and Dlama has paid off.

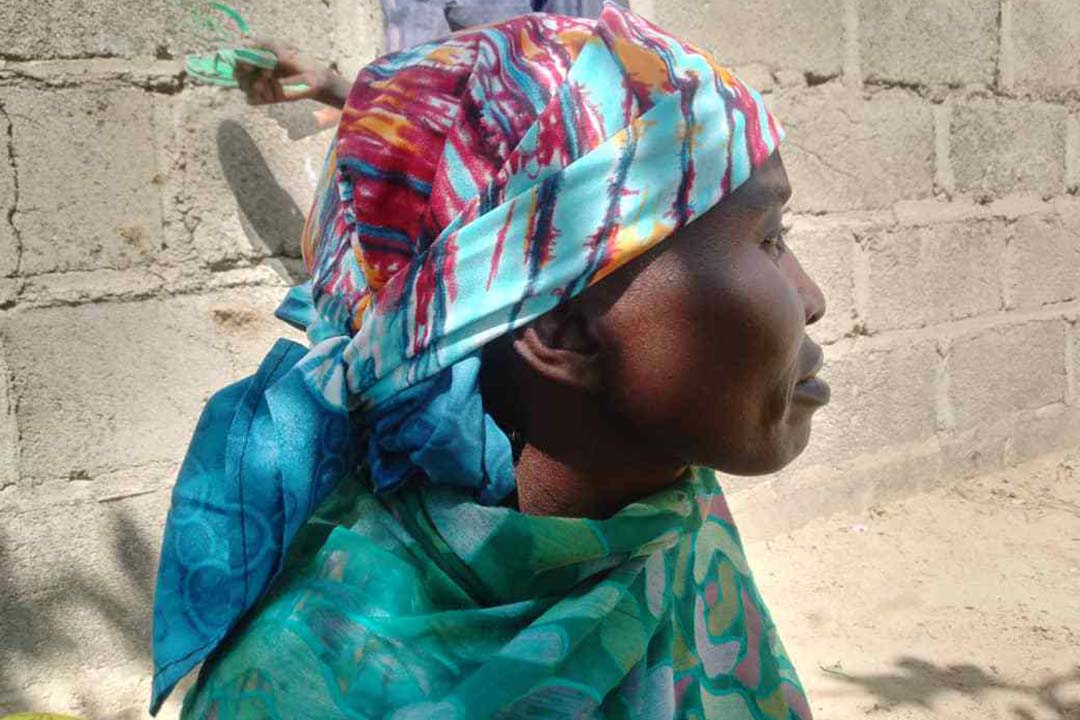

On a balmy day in August, Fanna Garba looked forlorn as she gazed at the clouds, humming some inaudible words before finally settling down in a chair in front of her shelter in Alakaramti, a village on the outskirts of Maiduguri. The 36-year-old mother of four was plainly lost in thought. She adjusted her pink hijab, then finally mustered the courage to speak of her three years in Boko Haram captivity.

Garba could not remember the exact day when she, alongside many other villagers, was taken away from Bama, her hometown. It was sometime in 2013. She was doing some chores in the house; then came the sounds of guns. She immediately knew it was Boko Haram.

Have you read?

"Before I could flee the house with my family, the terrorists had come in and they forcefully took me and my four children away to their camp. My husband was lucky to escape. If he had not and was taken with us, he probably would be turned into a [jihadist] fighter," Garba said.

While in Boko Haram captivity, Garba said she and other women were made to work as cooks for the group's fighters. "They [the terrorists] would ask us to fetch firewood from the bush and vegetables to make soup – of course, with some of them guarding us so we would not attempt to escape," she said. "It was a terrible experience. They put fear in us; they told us they could kill us at any time."

That long, frightening period came to an end sometime in 2015 when the Nigerian military launched attacks on the terrorists and freed some captives. Garba numbered among them

"I suffered throughout my four-year stay in the bush, where Boko Haram built a camp. I am thankful I have been out of captivity for over a year now. But the challenge is that things are hard for me and my nine children. Feeding them is extremely difficult."

– Zara Hamman

The newly freed people were taken to an IDP camp in Maiduguri. In 2021, Garba left the camp and resettled in Alakaramti.

But while in the IDP camp, Garba spoke of how people like Ochojila and Dlama helped her and other women regain their sense of themselves, and place into perspective the extreme beliefs Boko Haram had insisted they adopt.

"Boko Haram would order you not to vaccinate your children because it is haram, citing some religious injunctions. But now I know they told us lies. Health workers often tell us about the importance of giving our children routine vaccination. All my four children take these vaccinations whenever the opportunity presents itself and they are all healthy," Garba said.

Rose Dauda, a 30-year-old from Pulka town in Gwoza Local Government Area, was held captive by Boko Haram for five years until her rescue about three years ago.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

"They [the terrorists] were very violent. They insulted us and told us not to allow our children to go to school or health centre for routine jabs. However, I have been able to discard their doctrines, thanks to deradicalisation sessions with counsellors. My five children will no longer miss routine vaccinations," she said.

Zara Hamman, a widow who hails from Gwoza town, said after spending four years in Boko Haram captivity, she was rescued in 2021. Counselling sessions have helped her jettison the ideology forced on her by the jihadists.

"I suffered throughout my four-year stay in the bush, where Boko Haram built a camp," Hamman, 36, said. "I am thankful I have been out of captivity for over a year now. But the challenge is that things are hard for me and my nine children. Feeding them is extremely difficult."

When Zulum, the Borno State governor, decided to close most IDP camps in the state, humanitarian organisations criticised the move, saying it was hasty and would throw the IDPs into a renewed state of acute vulnerability. As of 2022, Human Rights Watch (HRW) estimated that over 200,000 displaced people had been thrown into deeper suffering and destitution.

"Acceptance is still a work in progress in many communities. Meanwhile, NGOs like ours have contact persons who work with the lawans and bulamas (community leaders) to monitor the progress of women that we have counselled and have been reintegrated into communities."

– John Ochojila, clinical psychologist

"The Borno State government is harming hundreds of thousands of displaced people already living in precarious conditions to advance a dubious government development agenda to wean people off humanitarian aid," Anietie Ewang, Nigeria researcher at HRW, wrote in the report, Those Who Returned Are Suffering': Impact of Camp Shutdowns on People Displaced by the Boko Haram Conflict in Nigeria. "By forcing people from camps without creating viable alternatives for support, the government is worsening their suffering and deepening their vulnerability."

Similarly, Crisis Group, in a January report, said the accelerated closure of IDP camps and the return and resettlement of their inhabitants to communities would not help the Borno State government accomplish its objective of turning the page on a long-running insurgency.

Nevertheless, it does not look like the state government will go back on its decision. At the inception of his second tenure on May 29, Governor Zulum said his plans would be to reopen more communities to accelerate the revival of the state's economy – which has been battered by the Boko Haram conflict.

As more communities reopen and the displaced people resettle in them, Ochojila said the challenge many of his patients trying to reintegrate will face is discrimination by the rest of society. However, he said he is aware the authorities and NGOs are working on carrying out sensitisation drives.

"Sometimes, the freed captives are rejected by their own families. Acceptance is still a work in progress in many communities. Meanwhile, NGOs like ours have contact persons who work with the lawans and bulamas (community leaders) to monitor the progress of women that we have counselled and have been reintegrated into communities," he said.