Here’s how reducing malaria can add $16 billion to Africa’s GDP every year

Meeting global targets to reduce malaria by 90% by 2030 will not only save thousands of lives, but also add $126 billion to Africa’s GDP.

- 1 July 2024

- 3 min read

- by World Economic Forum

- More than 600,000 people die from malaria every year, with 95% of those deaths in Africa.

- Reducing malaria cases by 90% by 2030 could not only save lives, but also increase Africa’s GDP by $126 billion, according to a new report.

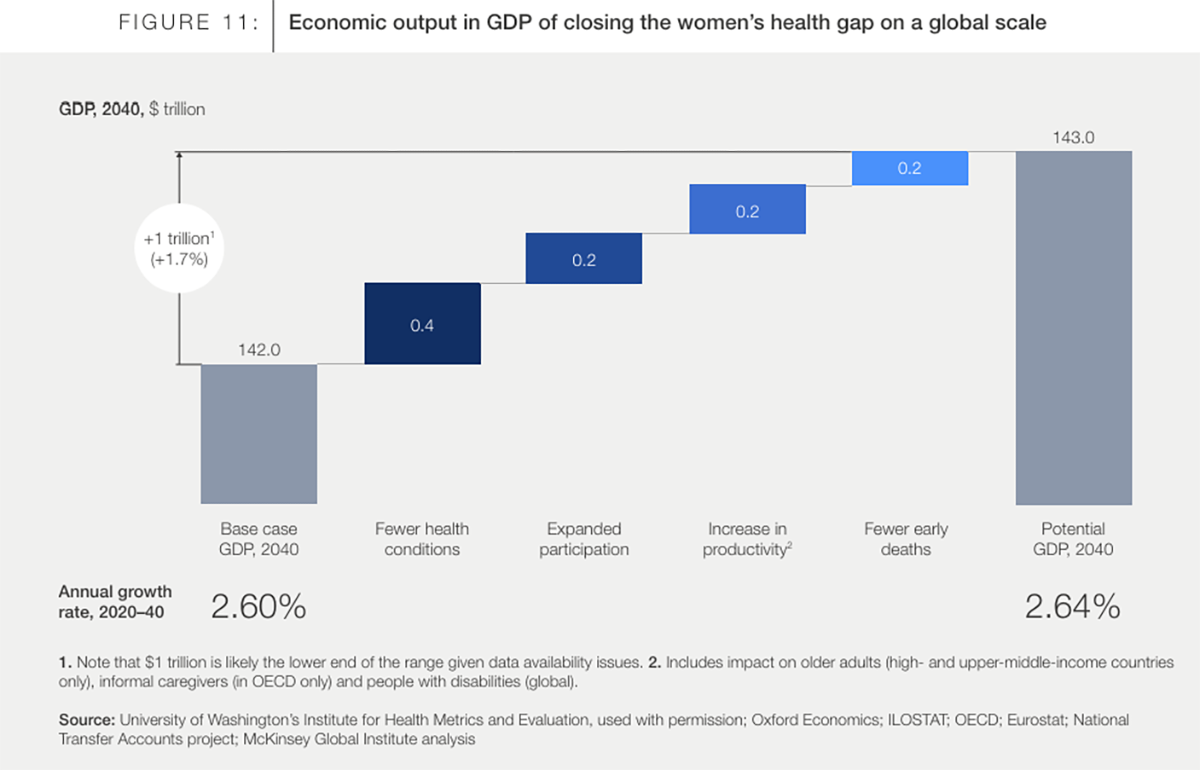

- Similarly, closing the women’s health gap could enhance the global economy by $1 trillion annually by 2040, according to a recent report by the World Economic Forum.

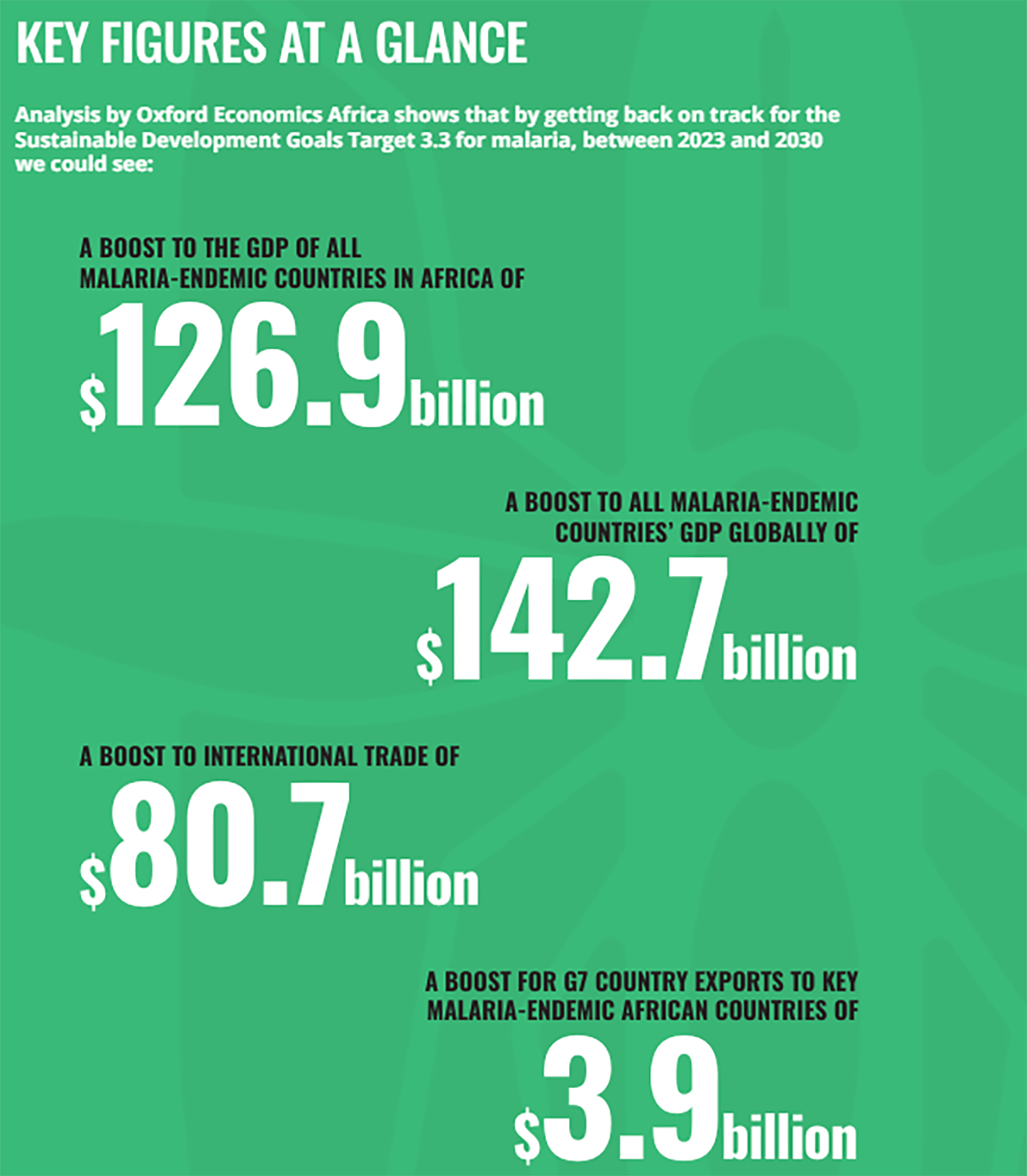

Achieving the World Health Organization (WHO) target of reducing malaria by 90% by 2030 would not only avert 600,000 deaths annually, but could also increase Africa’s GDP by $126.9 billion – or $16 billion per year.

This is a key finding in The Malaria ‘Dividend’ report by Malaria No More UK, which is based on analytics from Oxford Economics Africa.

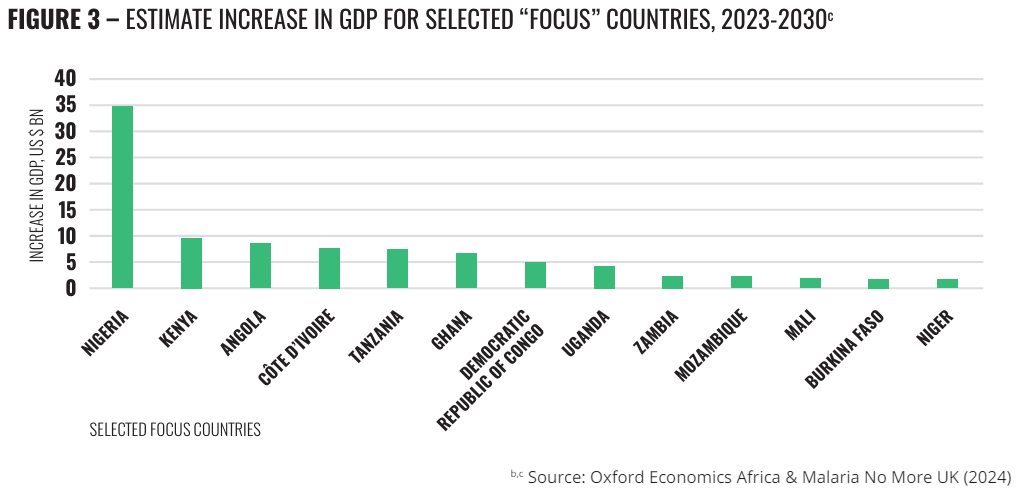

This economic uplift would add $35 billion to Nigeria’s economy – already one of the largest on the continent – and could increase international trade by $80.7 billion by 2030, according to the report.

Have you read?

Image: Malaria No More UK

Malaria reduction targets

Currently, the world will not meet the WHO’s target of at least a 90% reduction in case incidence and mortality rates of malaria by 2030. Of the 600,000 people who die from malaria every year, 95% are in Africa – and most are children under five years of age. Meanwhile, adults of working age are affected as they take sick leave to care for their families or themselves, leading to income loss and rising healthcare costs. This all carries a growing economic burden.

Efforts to curb rates of malaria have slowed in recent years due to disruptions from climate change, conflicts, drug and insecticide resistance as well as the COVID-19 pandemic. Together, these factors have helped create a “perfect storm of conditions holding back progress,” the report says.

Image: Malaria No More UK

Rallying greater support

Prior to this, malaria interventions prevented 2.1 billion cases and 11.7 million deaths between 2000 to 2022, according to the WHO.

“While great progress was made in the first two decades of the century – the global mortality rate for malaria halved between 2000 and 2015, and case incidence fell by 26% – the fight is far from over,” the report explains.

But the target to reduce malaria by 90% by 2030 “could still be met through concerted efforts,” it says. New vaccines, ‘next generation’ bed nets and other “potentially game-changing innovations” will play a key role.

Reducing the economic impact of today’s high malaria rates means countries could improve their broader healthcare prospects, with the report pointing to enhanced diagnostic capacities and healthcare workforces as examples.

Ongoing support to reduce malaria and many other diseases is paramount to strengthening the nexus of health and economic security worldwide, such as the work done by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and The Global Fund.

“In the near term of the next 18 months, the necessity of adequately funding both the Global Fund and Gavi at their upcoming replenishments cannot be overstated,” the report says.

Image: World Economic Forum

The economics of health

The connection between health and economic security is far-reaching. For example, investments addressing the women’s health gap could enhance the global economy by $1 trillion annually by 2040, according to a recent report by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with the McKinsey Health Institute.

Improving women’s health could help them avoid 24 million life years lost due to disability and provide a $400 billion uplift to the economy, the Forum’s report highlights.

In the US, diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition at $413 billion per year and Australia’s GDP could be approximately $4 billion per year higher if the health of people in fair or poor health was improved.

The link between health and global wealth is clear, as illustrated by the potential to add $16 billion per year to the GDP of Africa by tackling just one of many preventable diseases.

More from World Economic Forum

Recommended for you