A desert 4,000m in the sky: Nepal’s health workers reach some of the world’s most remote communities

In the shadows of the world’s highest peaks, health workers in remote Upper Mustang traverse some of the world’s toughest terrain to connect the country’s most sparsely populated region to essential healthcare.

- 24 March 2025

- 8 min read

- by Kelly Warden

Undulating between three and five thousand metres above sea level and stretching over three thousand square kilometres, rugged Upper Mustang is nestled in the contours of Nepal’s border with occupied Tibet.

Majestic snow-capped peaks contrast against the sunburnt terrain, where rain is as sparse as its people.

Only 3,322 people live here, with a population density of 1.49 persons per square kilometre. This tiny population is declining further, as changing weather patterns damage homes and threaten livelihoods, forcing families to abandon agriculture for opportunities in faraway cities.

Despite its small population, Upper Mustang and its people remain a living, breathing fortress of Tibetan culture. Communities preserve the ancient Tibetan language and ways of life, as well as the Buddhist religion and practices.

Also referred to as ‘Lo,’ meaning ‘North’ in Tibetan, Upper Mustang is home to the Lowa people.

“Sky caves” carved high into the red earthen valleys are believed to be the original dwellings of the first ‘Lowa’ people, who came down from the north of Tibet in the 8th century. Today, monasteries chiselled into the cliffs are still alive with the chanting of Buddhist monks in crimson robes.

“The entire region of Lo is completely homogenous and almost identical to Tibetan culture,” writes Dr Tashi Gurung – born and raised in Upper Mustang – and now a researcher at the Arizona State University, specialising in climate change, sustainability and migration in the Himalayas.

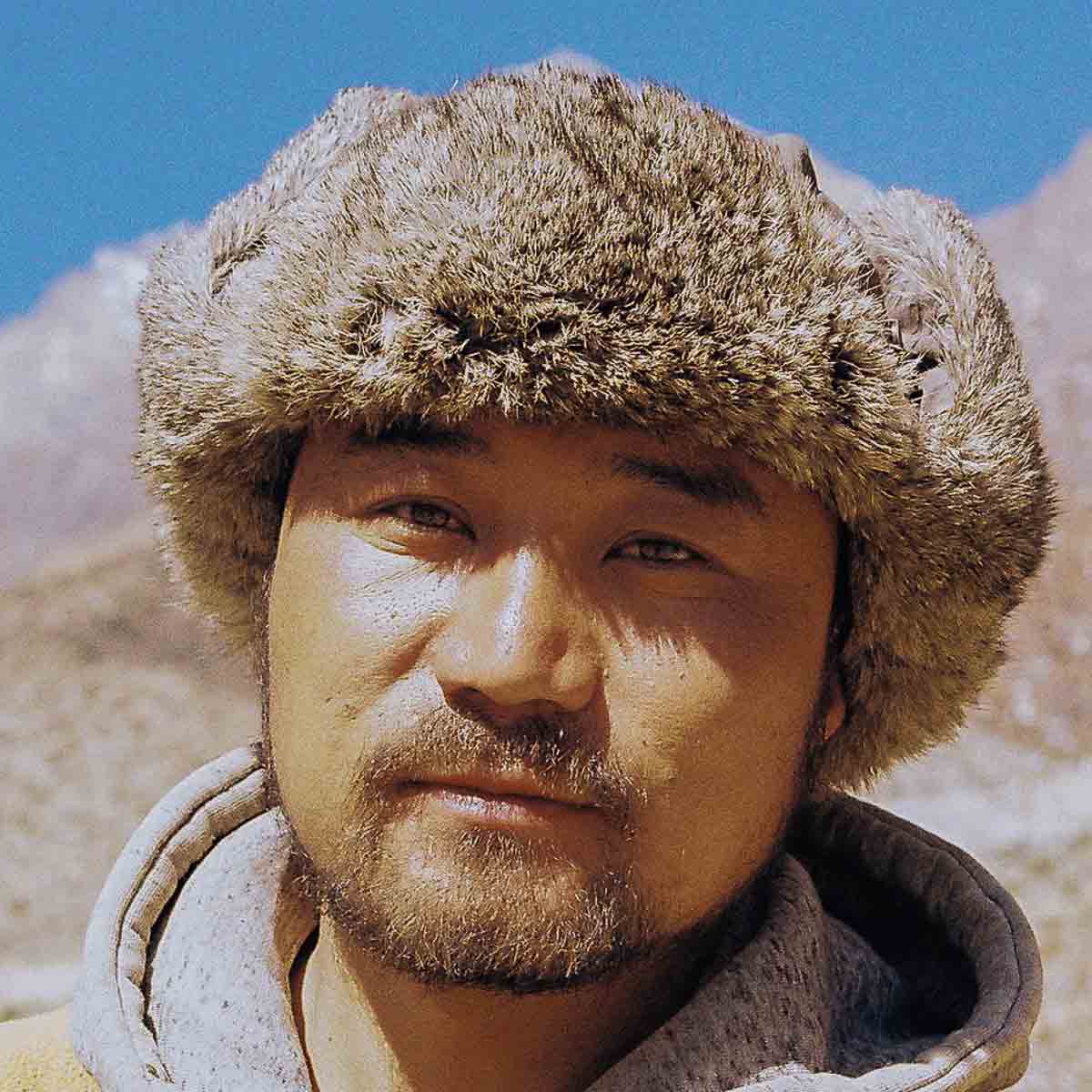

But navigating this nexus of ancient culture in a vast high-altitude desert poses a foreboding challenge for local health workers, who are often young professionals that have moved to the region from other parts of Nepal.

“I consider myself lucky to be able to provide these health facilities in this remote area,” says Suresh Kathayat, paramedic at Chhonhup Health Post.

“When I was little, I remember a lot of people falling ill and not even having basic medicines like paracetamol in my remote village.

“So, right from childhood I always wanted to study paramedics and join the health stream.”

On top of his day job, Kathayat is learning Sanskrit to bridge the language gap between him and his patients, who speak a Tibetan dialect and cannot understand Nepali.

“Other difficulties like power cuts are more frequent during the winter,” says Kathayat. “For almost three months the water freezes and the supply is not there.”

“We boil the ice then wait [for it to be] cold, and then work,” explains Suresh’s colleague and lab technician, Sushma Rai.

Winters in Upper Mustang are harsh and extreme, as temperatures drop as low as -30°C and snow builds up to the hip.

Many locals flock to the nearest city – Pokhara – to wait out the winters, but health workers will stay to care for those locals and families who remain.

Seasonal challenges for health workers

“In every season we face a lot of problems,” says Kaghendra Bohra, who oversees the management of five health posts servicing 2,137 people spread across Upper Mustang’s Varagung Muktichhera rural municipality.

“In winter season we face snow or water, in monsoon season we face flood […] in summer season we also face the wind.”

“But our health workers go… and they will take risks.”

From Kagbeni village, known as the ‘gateway to Upper Mustang’, Bohra and his team travel by foot to some of the hardest-to-reach parts of the region.

One of the toughest treks is to a village 4,200 m above sea level – only 600 m lower than Europe’s highest mountain, Mont Blanc – and a 30 km walk from Kagbeni.

“For the pregnant women and children living there, it is difficult to come to the health post because of the difficult geographic terrain,” says Sanjita Singali Magar, who has been providing antenatal and postnatal care to women in the municipality for almost two years.

Magar and her team do regular rounds to every household in their municipality, identifying women who are pregnant and following up with home visits if they cannot come to the clinic. They also keep track of every woman’s due date, so they can attend homebirths.

After the babies are born, the team continues visiting to “check the condition of the children, whether they have received vaccines, [and] whether their growth monitoring has been done,” Magar says.

Today, Magar and her colleague Sushil are visiting 13-month-old Kunga Gurung and his mother, Lheachi, who runs a guest house in Kagbeni village.

Their short walk through the village is sidetracked by conversations with other mothers they pass in the streets, reminding them when the next round of vaccination sessions will be held in the clinic.

When they reach the guesthouse, Lheachi invites them for tea before the check-up.

“My son has received all the vaccines until nine months old here at Kagbeni health post,” Lheachi says, bouncing Kunga up and down on her lap.

“If we didn’t have this facility, it would be very difficult for us.”

The impact of a changing climate

Historically, Upper Mustang receives very little, yet very predictable annual rainfall. It is formally classified as a desert. With Annapurna looming to the East and Dhaulagiri to the West, giant peaks have protected the valley against heavy monsoon rains as long as the mountains have stood.

In this arid landscape, farmers irrigate crops and feed their animals with water from streams and rivers fed by glaciers, and this has sustained their livelihoods for generations.

“But these days we are not cultivating even a single field,” says 31-year-old Jigmae Gurung, a farmer and hotelier from Samar village, about 14 km upstream from Kagbeni.

Temperature and rainfall patterns are changing in the valley, Gurung explains. The dry months have dried up completely – leading to drought – while the wet seasons bring record-breaking downpours, with a rapid increase in storms and rainfall in recent years.

Gurung was forced to abandon his family’s buckwheat and barley crops ten years ago, as the climate became unfavourable to farm grain.

“It is what we have grown for generations,” he says. “Now we are just cultivating some trees, like apple trees.”

As glaciers melt, some rivers are drying up and some are overflowing. “There has been flooding due to excessive rainfall in the past 5 to 7 years, and streams that hadn’t flooded in 20 years have overflowed, and landslides occur more frequently,” Bohra says.

Last year, Kagbeni suffered devastating flash flooding, damaging dozens of homes, crops and the boarding house for the local monastery

“All due to climate change,” Bohra says.

Dengue risk

In Mustang, temperatures are rising steadily every year. Scientists warn this warming in the high mountain regions is also creating favourable conditions for the spread of diseases carried by mosquitoes, like dengue.

“In the past, our vector-borne diseases were endemic in the lowland terrain, but now all these diseases are shifting to the highlands of Nepal,” says Dr Meghnath Dhimal, Chief Research Officer at the Nepal Health Research Council, specialising in climate change and health.

“We reported vectors of disease like [the] Aedes aegypti [mosquito]… up to 2,000 m in Nepal.”

“That means regions up to 2,000 m are at risk of dengue transmissions... [and] our new studies are going in much higher altitudes.”

In Kagbeni health post, sitting at 2,800 m above sea level, Bohra warns that dengue cases have been reported in their neighbouring municipality, “and the mosquitoes are now found here,” he says.

These cases were imported – as in, the persons were diagnosed in Mustang but had been infected elsewhere. However, Bohra is concerned that mosquito sightings in Kagbeni means the opportunity for local transmission of imported cases.

“We need investment for the prevention and control of climate sensitive disease… and one option could be the vaccine against dengue fever,” says Dr Dhimal.

“And certainly, the free distribution of vaccines to the poor countries who are least responsible for the cause of climate change.”

Have you read?

Climate justice

In 2023, Nepal was responsible for only 0.107% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The average person in high-income countries emits more than 30 times as much as in low-income countries like Nepal, and yet these communities are the first and worst impacted by climate change.

In the 1990s, Nepal’s first self-proclaimed climate refugees came from Dhye, in Upper Mustang – who were driven out of their village when water sources dried up.

The population of Mustang today is half of what it was in 1971. In Gurung’s village, he says he is the only one is his generation who has stayed, while the rest left for opportunities in Nepal’s cities, or abroad.

“In these ten years there is not a single person who has come back here,” he says. “It’s very hard.”

Yet, families continue to live and work in Upper Mustang, and health workers are being challenged from all fronts to provide the healthiest possible future for the next generation of children, keeping this stronghold of Tibetan culture alive.

Which is why strengthening healthcare systems, financing vaccines and investing in training and capacity building for health workers in Upper Mustang is central to Gavi and UNICEF’s joint efforts in the region.

As the immunisation focal point for UNICEF in Nepal, Health Specialist Adhish Dhungana oversees the cold chain management for vaccine delivery and distribution across all of Nepal’s 77 districts.

“We have to work together to ensure moving forward we can build a better health system and improve health outcomes,” he says.