Could we get a pandemic vaccine in 100 days?

The first COVID-19 vaccines took a year – lightspeed by usual development standards – but global health experts believe we can go much faster.

- 17 March 2022

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

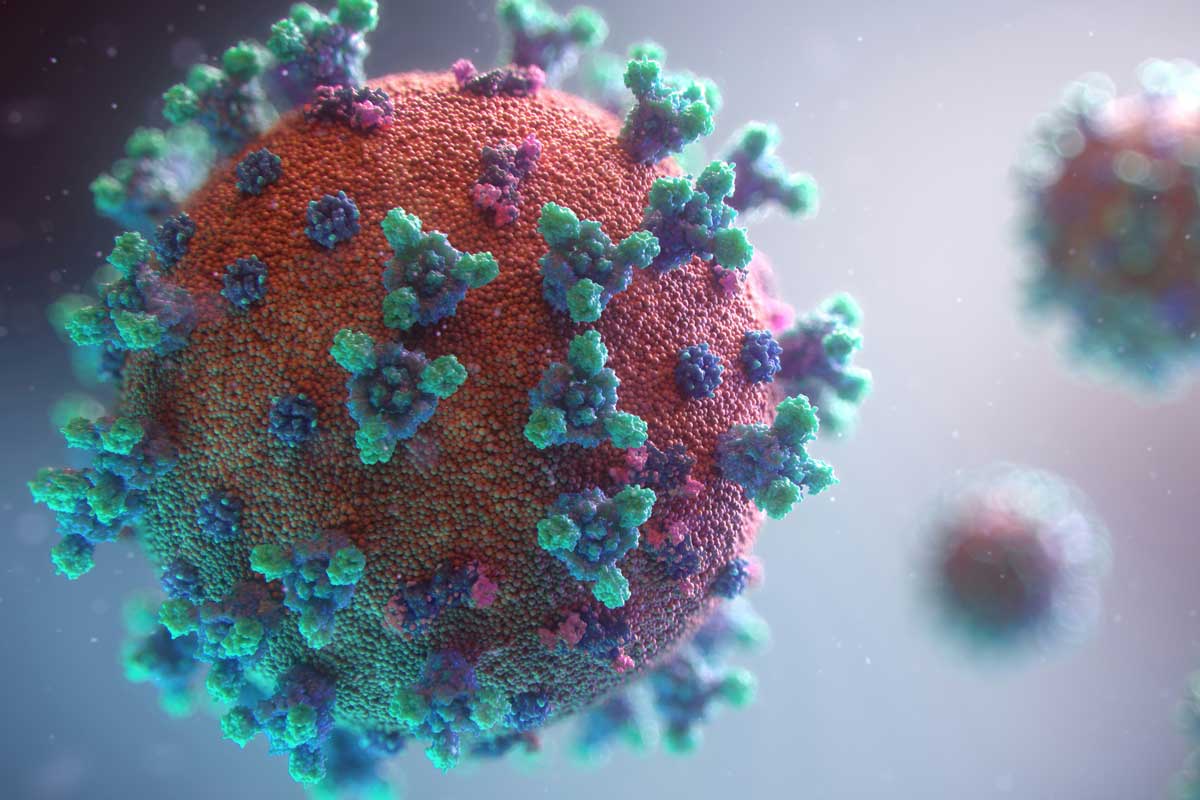

Just days after SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered the virus was sequenced. Exactly 326 days after the sequence was available, the first COVID-19 vaccines were given emergency authorisation.

By any measure, this was an extraordinary win for science. But it’s worth noting that in those 326 days there were 70 million cases and 1.6 million deaths – and these are likely underestimates.

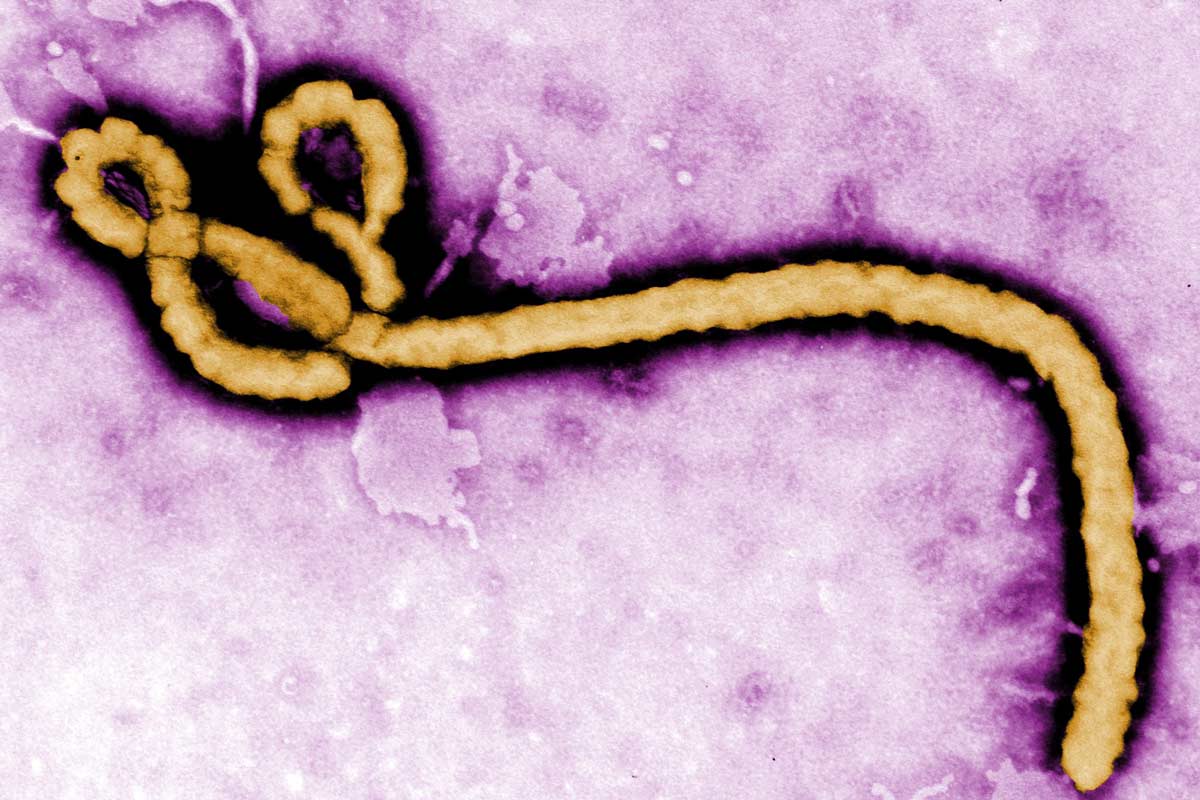

Getting to 100 days will require another step-change. The phasing of preclinical work, clinical trials and regulatory review will need to maximise efficiency in their planning. Scientists will also need to work on “prototype vaccines” for known pathogens in different viral families.

To prepare for the next pandemic – an evolutionary certainty – the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has stated a ‘moonshot’ goal: to get vaccines ready within 100 days after the next pandemic pathogen is identified.

This might seem extraordinarily ambitious, but many believe it’s not impossible. Researchers, including those from CEPI, writing in The New England Journal of Medicine, explore what it would take to make that goal a reality.

They spoke to 46 representatives from vaccine-development firms, international organisations, regulatory agencies, academia, and the media to identify innovations that could speed up development and challenges that would need to be solved in order to meet the 100-day goal,

The strategies the group identified fell into five categories: leveraging existing insights on emerging pathogens and development technologies; innovation in the vaccine-development process; using advanced analytics, better data and information sharing; and continuously reviewing evidence for swift approval. These alone could shorten the time to 250 days, they estimate.

Have you read?

Getting to 100 days will require another step-change. The phasing of preclinical work, clinical trials and regulatory review will need to maximise efficiency in their planning. Scientists will also need to work on “prototype vaccines” for known pathogens in different viral families. This could allow us to rapidly adapt a prototype to fit a pandemic pathogen. Work on vaccines against MERS-CoV and SARS contributed greatly to the speed at which vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were created.

Developing robust biomarkers of a sufficient immune response to vaccination will be critical they say, to shorten the time a clinical trial will need to run for.

Improving manufacturing capacity to facilitate rapid production and scaling, ensuring a sustainable supply of raw materials, and developing clear procedures will be needed as well. Finally, they say, investing in global capabilities into the assessment of risk and severity will be key to identifying who is at highest risk and informing risk-benefit estimates.