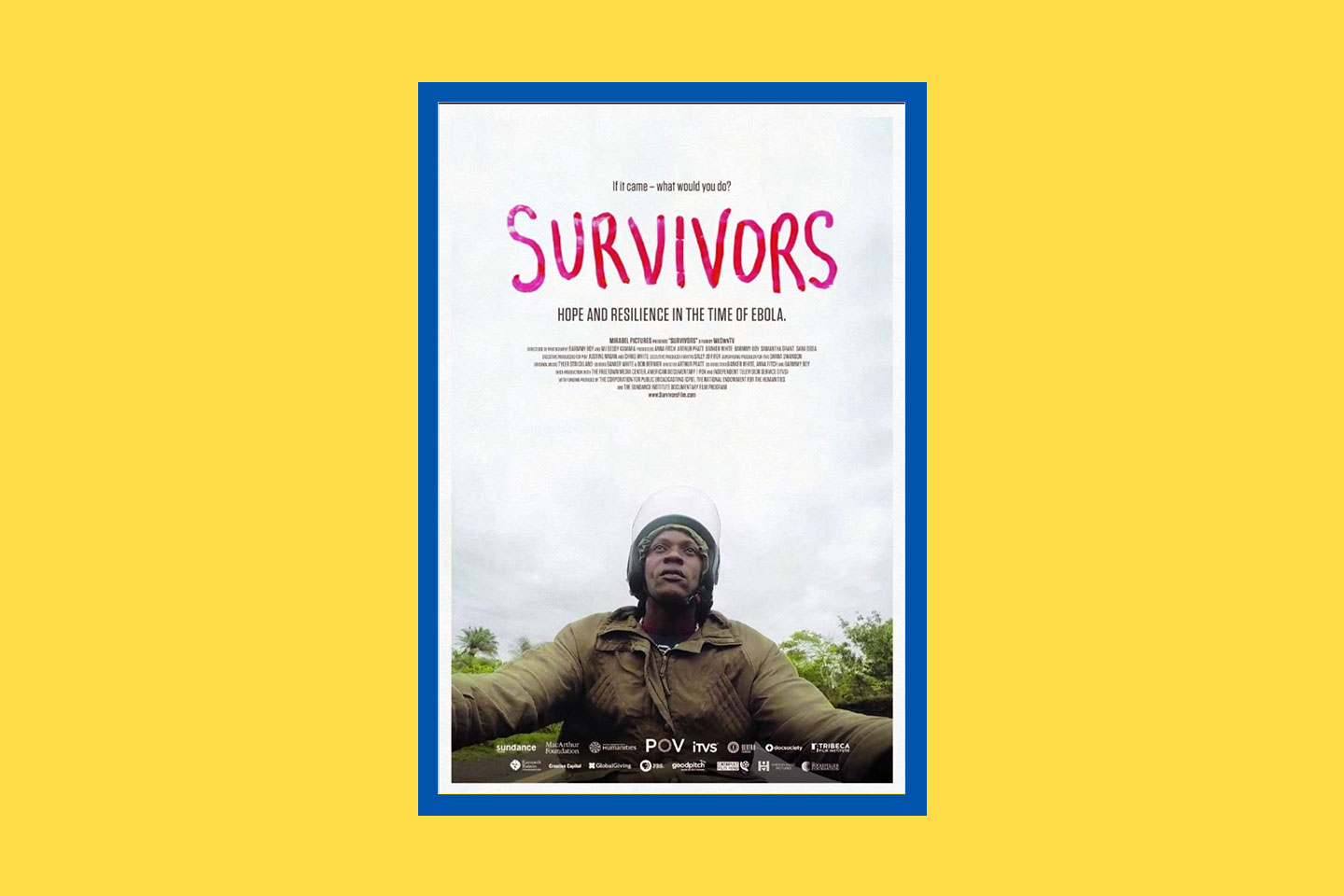

Review: Survivors – Hope and Resilience in the Time of Ebola

The Sierra Leonean documentary is a complex portrait of courageous solidarity amid contagion.

- 10 September 2021

- 3 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

In Sierra Leonean filmmaker and pastor Arthur Pratt’s telling, when Ebola came to West Africa, it carried a doubled threat. The first was infection with the virus which, during the 2014-16 outbreak, carried a 50% chance of death. The second was harder to test for, but equally existential.

“We need to do it. Because if we don’t do it, nobody will.”

Pratt explains in voice-over: “When it came, I saw Ebola as an enemy to West Africans, because it attacks the very fabric, the very foundation, of our beliefs. The foundation of what makes us Africans, and that is our ability to associate with each other – our ability to come into contact with one another.”

How does a cultural identity predicated, in Pratt’s view, on the warmth of human connection weather an epidemic that demands social isolation? Scenes of soldiers in fatigues dispersing crowds at Freetown marketplaces, or Red Cross workers with megaphones informing wharf-side slum communities of the penalties for washing dead loved ones – in other words, of the prohibition against a dignified goodbye – read as ominously as shots of zippered body bags being loaded onto trucks.

But Survivors, a remarkable 2018 documentary made by a collective of Sierra Leonean filmmakers helmed by Pratt, is not a tragedy. It exists as a refutation of the narratives of helpless victimhood that Pratt saw in western coverage of the Ebola epidemic. Following four main characters, two nurses, an ambulance driver, and a Freetown street-kid, its tells a complicated, intimate story of radical fellowship in hard times.

Have you read?

The film’s most brutal, most luminous moments show its characters figuring out how to act – rather, who to be – beyond the guide-rails of protocol. In one instance, ambulance driver Mohamed Bangura and his co-worker, nurse Kadija Kanu, are sent to pick up an eighteen-month old patient. Bucking guidance on physical distancing, Kadija suits up in a protective yellow suit and climbs into the back of the ambulance, cradling the baby on her lap. As the door slams on the child’s mother, her grief is audible: ragged and exhausted.

The ambulance speeds away towards a horizon blurred out by dust, and we hear Mohamed speaking. “Kadija, I don’t want you to do that again,” he says. “Holding sick kids in the back.” “But I am a nurse,” she answers. He argues: “Volunteering to do certain things can lead to serious problems,” – the threat of infection doesn’t need naming. “If we don’t do our jobs, this thing will never end,” Khadija says, firmly. “We need to do it. Because if we don’t do it, nobody will.”

Soon it’s Mohamed, clearly scared, reluctant, nevertheless agreeing to carry a patient down a steep hill on his back when a stretcher won’t do. Then Mohamed and Kadija bring a critically ill patient – we catch a glimpse of her face, simultaneously slick and crusted with blood – to the hospital, though she comes to them without the necessary paperwork. Kadija’s disappointment and rage when the hospital staff refuse to admit her is heart-breaking. “Nobody wants to take responsibility,” she curses. And there’s the deeply Christian nurse Margaret Kaba Sesay, who prays with her patients on the Ebola ward. “Are you a Muslim?” she asks one ill woman. “That’s good. Religion isn’t here to separate us.”

Contagion, of course, is. But it can also be resisted. “I need to tell the world how my people survived Ebola,” Pratt says. “We’ve seen people making sacrifices, sacrifices worthy enough of mention.” It’s good to be reminded of what courageous solidarity can achieve.