Blue skies thinking

- 18 September 2018

- 10 min read

Rich countries abound with innovative technocrats and advanced equipment, while poorer nations struggle to create, afford and implement new technologies.

That’s the cliché. But the reality can be very different. When it comes to aerial drone technology, lower income countries are flying high. Not only are they embracing the use of flying drones, but they are also helping to drive the evolution of drone designs, and creating new markets for drone services, in partnership with private companies and the development community, including Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

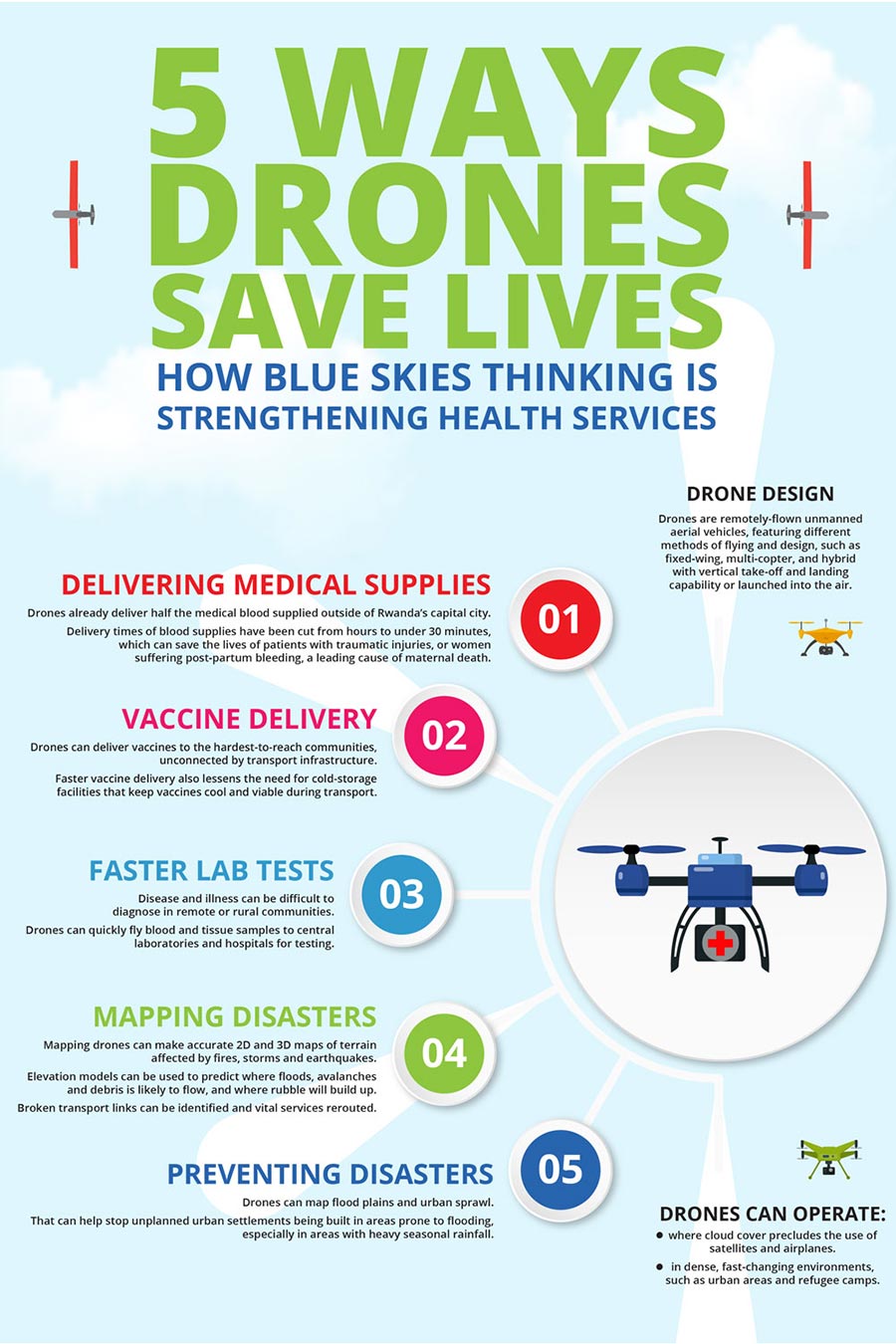

This sudden and stunning lift-off is often in response to the severe challenges many poor countries face in delivering health services to hard-to-reach communities. Medical products are usually stockpiled within the largest cities. Distributing them to distant communities unconnected by reliable road and rail services is expensive and time-consuming. That uses precious financial resources, and can jeopardise the vitality of biological products, such as blood and vaccines, which may perish if they do not quickly arrive.

But drones are capable of flying these life-saving interventions quickly, directly and cheaply to their destinations. That’s why across Africa and beyond, partnerships are being forged that are accelerating the development and use of aerial drones, potentially transforming the market for drone technology and the provision of healthcare to millions of people.

Rwanda’s life-blood

In 2016, Rwanda became a prominent, early adopter of drones, using them to transfer blood supplies between medical facilities. The drone fleet and launch sites are designed and run by the California-based robotics company Zipline, supported by a partnership with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and UPS, the international package delivery and supply chain management company.

Much of rural Rwanda is mountainous, which can make it difficult for aerial vehicles such as drones to land. So Zipline innovated, creating a new fixed-wing drone that is launched by a sophisticated, powered catapult. When the drone arrives at its delivery site, instead of landing it flies low, releasing its payload in a package that falls softly to the ground, its descent slowed by a disposable parachute.

One minute before it arrives medical staff receive a text message to alert them, and so are already waiting, ready to collect the blood as soon as it is delivered. The drone then returns to the launch site, where it is caught mid-flight by a cable system that returns it safely to earth, to be readied to fly again.

This new type of drone gets round the need to building runways and can supply rural hospitals and medical centres with routine or emergency supplies of blood within minutes, rather than hours it would take to transport by road. For someone haemorrhaging during childbirth, or after a traumatic injury, this fast service can be the difference between life or death.

This service currently delivers half of the country’s blood supply outside of the capital. It now has plans to scale up its operations to serve the rest of Rwanda.1

Gavi has helped play an important role in this expansion, through its financial and political support. Though the drone delivery service initially focused on blood supplies, the goal is to expand it to deliver medicines and vaccines.

Since then, Gavi has convened meetings between leaders in business, philanthropy, investment funds and academia, to discuss new approaches to vaccine delivery that benefit countries, communities and technology companies.2

These new approaches may overcome many of the physical barriers to immunisation, including the absence of roads. It will also reduce the requirement to keep vaccines cool for days on end – which currently relies on expensive “cold chain equipment”.

The more quickly vaccines can be transported from central depots to clinics in the field, the fewer fridges and cool-boxes are needed to store them along the journey.

The drone challenge

Rwanda is not the only country embracing the new use of new drone technology.

Tanzania is home to the Drone X project. With funding from the German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), the Tanzanian government is collaborating with Wingcopter, a commercial manufacturer of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV).

These partners are testing how to use drones to transport emergency medical supplies, blood and health products from the city of Mwanza’s Medical Stores Department to Ukerewe District Hospital on Ukerewe Island, and the return transport of biological samples to be tested in Mwanza’s laboratories. Ukerewe Island is the largest inland island in Africa, isolated within the waters of Lake Victoria, which is itself the second largest freshwater lake in the world. It usually takes a day to supply the island, involving journeys by truck and ferry, which run to a fixed schedule.

The Drone X project is now examining which UAVs may best transport different medical projects. Development partners include the John Snow, Inc. inSupply project, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is advising on which health products are best suited for delivery by drone, and can be linked to wider supply chains.

As part of the challenge, drones will fly along a corridor nestled between military airspace and communities that are both large and hard-to-reach, making the Lake Victoria Challenge ideal for drone operators to rehearse operations and optimise their risk assessments.

They compete to complete a series of real-world tasks, including transporting medical parcels, and using vertical take-off and landing platforms. Drones will have to pick up and deliver as many packages as possible within two hours, distribute emergency packages, and survey and map a remote location in the shortest amount of time. They must perform these challenges without violating protected airspace, using commercially available technologies, flying at a range of altitudes and temperatures.

The Lake Victoria Challenge is the first event of its kind in Africa.4 Across the continent, only 34% of people live within two kilometres of a road that can be used in all weather conditions.5 That means the majority live in places that are inaccessible or vulnerable to being cut-off.

Drones can reach these places, however. They also have the potential to become a significantly cheaper mode of transport, lowering the price per kilogramme per kilometre of moving cargo to communities unconnected by road or rail. Around the world, vaccination rates have stalled in recent years, as it becomes more difficult to reach children living in more remote or inaccessible areas. Stimulating innovation in drone technology may better enable vaccines to be delivered to the hardest-to-reach children, helping to achieve Gavi’s goal of vaccinating 300 million more children by 2020.6

Humanitarian aid

According to the Lake Victoria Challenge organisers, the global market for drone technologies could exceed US $ 125 billion.7 That market is already being shaped by the development community, which is helping to fund innovative drone companies.

The United Nations is also encouraging similar innovations that may help people in humanitarian crises.8 Here, the ability of drones to reach, examine and monitor places suffering natural disasters is as important as transporting cargo.

To date, drones have most commonly been used to take aerial images and map terrain.

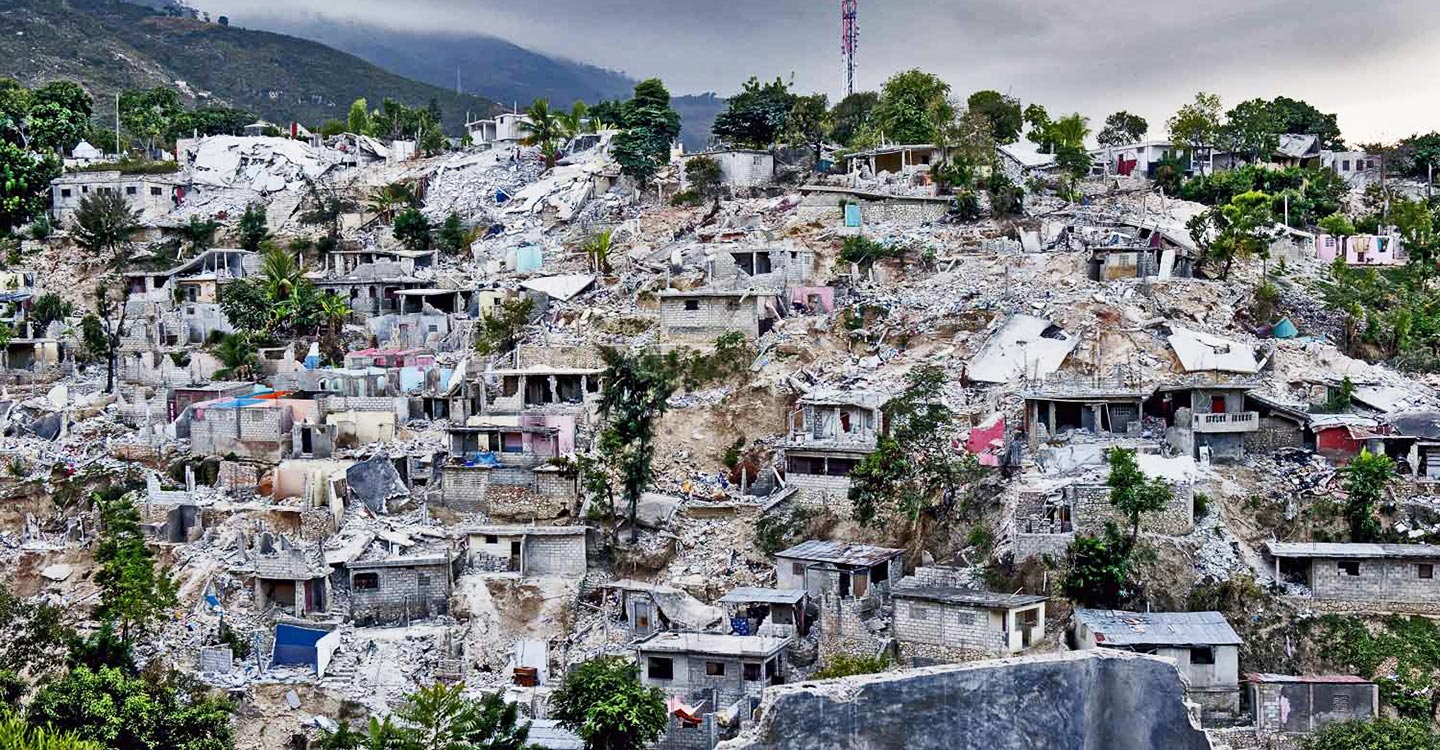

In 2010, a catastrophic 7.0 magnitude earthquake devastated the island of Haiti. In 2012, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) worked with the National Statistics Office of Haiti to conduct a census of areas most affected. Satellite images weren’t detailed enough, so IOM flew drones to create precise maps of buildings damaged within Haiti’s slums. Development agencies, including the Vaccine Alliance, have since provided support to help restore health services in the country.9

In 2015, the World Bank partnered with the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, local universities and the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team to map flood risks around the city of Dar es Salaam, one of Africa’s fastest growing cities. More than 70% of the population live in unplanned settlements at risk from flooding caused by twice-yearly heavy rains. The information provided by the drones is helping to mitigate the risk that floods will cause a natural disaster in the city.10

Consumer drones have been used to map communities hit hard by the magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Nepal in 2015,11 and to assess the damage caused by Cyclone Pam, which destroyed thousands of homes, schools and other buildings on the island of Vanuatu in the same year.12

Around the world, drones are increasingly being put to use to support and protect people in developing countries. To date they have also been used by Médicins Sans Frontières to transport biological samples across Papua New Guinea, from remote health centres to laboratories where they can be tested. In Malawi, UNICEF has conducted feasibility studies using UAVs to transport samples that would allow early infant diagnosis of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus.13

Fourth industrial revolution

In many circumstances, the drone technology being utilised is still nascent. But it forms part of what the World Economic Forum (WEF) has dubbed the Fourth Industrial Revolution.14

The First Industrial Revolution used water and steam power to mechanise production. The Second used electric power to create mass production. The Third used electronics and information technology to automate production. Now, according to WEF, a Fourth Industrial Revolution is building on the Third, characterised by the sort of advances seen in artificial intelligence and robotics used by UAVs.15

Like the revolutions that preceded it, the Fourth Industrial Revolution has the potential to raise global income levels and improve the quality of life for populations around the world, especially if it enables life-saving medical products, such as vaccines, to be distributed to those children and adults currently not protected.16

Zipline, the Drone X project and others are also showing the benefits of launching new technologies within a developing country.

That is contrary to a commonly-held view that products are best launched in richer countries before being expanded into poorer nations. Developing countries are often more attractive places to innovate, having a greater market need for new products and fewer regulations that may stymie their development.

That means companies can often launch new technologies more quickly in poorer regions of Africa or Asia, than in the United States or Europe. And the backing of organisations such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, means that such technologies can be tested, and scaled, more quickly.

The drone revolution is taking off. But it’s doing so in some of the least expected places. And for some of the most life-affirming reasons.