Where delivering health care means facing down armed bandits

In northwest Nigeria, some health workers are facing down danger to care for embattled communities.

- 21 June 2023

- 8 min read

- by Jesusegun Alagbe

Abubakar Ahmad has every reason to flee Goronyo town, in northwest Nigeria's Sokoto State. Indeed, many of his peers have left the area in recent years due to frequent attacks by violent gangs known locally as "bandits". But despite the insecurity in the area, Ahmad, a health worker, says he has chosen to stay to continue caring for the community.

"There is a fear that clouds over me each morning I step out of my home to do my job. You cannot tell if there is going to be an attack and if you are going to be the next victim," says Ahmad, who works at a health centre in the town.

“There is a fear that clouds over me each morning I step out of my home to do my job. You cannot tell if there is going to be an attack and if you are going to be the next victim.”

– Abubakar Ahmad, health worker, Goronyo town

Located on the Sokoto River, a tributary of the River Niger, Goronyo is one of the areas in Sokoto State that has come under attack on multiple occasions by bandits. Over 40,000 Goronyo residents have reportedly been displaced, while some youths have joined vigilante groups to protect their communities from the rampaging bandits, according to a report by national news outlet Premium Times.

Ahmad will not soon forget one of the bandit attacks on his village, after which he says he considered fleeing to a safer area. It was on 17 October 2021, when a horde of bandits, reportedly riding a fleet of more than 100 motorcycles, surrounded the Goronyo market and opened fire on the people. Local media outlet Daily Trust reported that 49 peoplersons were killed in the attack. Eyewitnesses recounted that the bandits disguised themselves as local vigilantes to infiltrate the market before carrying out the shooting.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

There have been similar attacks, both before and since, and Ahmad says these aggressions have prompted some of his friends to leave. In the end, Ahmad has always chosen to stay. "I thought of fleeing too, but I am so passionate about my people, especially those who have been displaced because of the attacks," he says, adding that the displaced are from Goronyo town and nearby villages like Kamitau and Malanfaru.

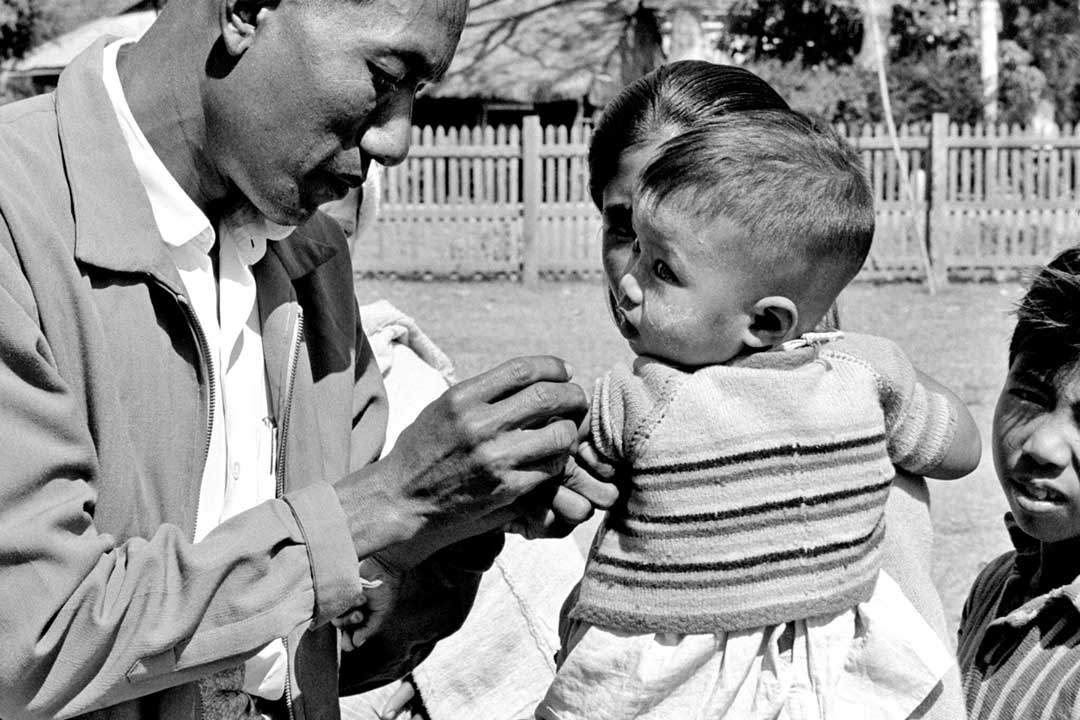

"If every health worker leaves, who will those who are sick turn to?" Ahmad asks. "I take care of those who visit the health centre and I also visit the Kumaji IDP camp here in the community to do my work. Particularly, I feel for children who are among the victims of these attacks. Some of them are brought to the health centre for routine immunisation and I encourage them and their guardians to stay strong."

Ahmad says some of the biggest challenges health workers like him face in a hostile environment is a heavy workload due to staffing shortages and poor working conditions in terms of poor pay, inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and irregular supply of medicines. Despite the challenges, the health worker says he derives his motivation from his service to humanity.

"A better way to motivate health workers like me working in volatile areas is for [the government] to provide adequate security and improved working conditions. If I go out every day knowing that my safety is assured, I think I am okay," he says.

"Bandits" is a catch-all term for armed gangs that kidnap people for ransom, rustle cattle, loot and extort villages in Nigeria. Over 100 gangs are believed to be operating in northwest Nigeria, a zone that is home to approximately 35.8 million people, according to a 2006 census by the National Population Commission (NPC).

Since banditry started escalating around 2011 in Nigeria – according to research by the think tank American Security Project – it has severely affected northwestern states including Sokoto, Zamfara, Kaduna and Katsina. North-central states like Benue, Niger and Plateau have likewise not been spared.

In the northwest alone, more than 453,000 people were displaced by persistent insecurity, encompassing the mounting threats of banditry, armed conflict, farmers' and herders' conflicts, and the pressures of climate change, as of early 2022. In early 2023, UNICEF reported that six million children aged under five and living in Sokoto, Borno, Adamawa, Yobe, Katsina and Zamfara states were food insecure; 2.9 million people in Sokoto, Katsina and Zamfara were considered "critically food insecure"

Have you read?

And even as the persistent peril threatens community health at multiple scales, health workers have been subjected to direct attacks. On several occasions, they have either been kidnapped or killed by the insurgents, a situation that has seen many leaving crisis-prone communities for safer towns and cities while some are emigrating from Nigeria due to the rising insecurity, according to the Human Resources for Health journal.

In 2021 alone, 49 incidents of violence against or obstruction of health care took place in Nigeria, according to the nonprofit Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition. Nearly half of those incidents involved the kidnapping of a least one health worker, with at least 30 health workers reported kidnapped during 20 incidents.

Professor Tanimola Akande, a public health expert and former member of the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Measles and Rubella, says much work needs to be done to tame banditry and calm other threats of violence to protect health workers' lives and improve health care in Nigeria.

"Although there is some level of progress in health care through funds provided by organisations like Gavi, there could have been a better level of progress if there was no insecurity," says Akande.

"The level of insecurity is bad, and, unfortunately, a number of health workers have lost their lives. It looks to me that we do not have enough military manpower to fight the war against insurgency and protect health workers. I think the military is trying its best, but certainly, it is not enough to protect health workers. And now, many health workers do not want to be posted to conflict-ridden zones for fear of their lives."

“Children are at risk of falling sick if they are not vaccinated and I feel a sense of duty protecting them from disease outbreaks. If my health was not protected when I was a child, I would probably not become a nurse today.”

– Buhari Ibni Saidu, nurse, Goronyo town

Despite the grim situation, Buhari Ibni Saidu, a nurse at the general hospital in Goronyo, Sokoto State, says his motivation to keep working, including giving children their routine jabs, is a sense of responsibility to promote public health.

"Children are at risk of falling sick if they are not vaccinated and I feel a sense of duty protecting them from disease outbreaks. If my health was not protected when I was a child, I would probably not become a nurse today," Saidu says.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

"However, I would like to implore the government to pay attention to health workers' welfare and their safety. If we continuously feel unsafe, it may dampen our morale ultimately. But I hope it never comes to this."

Some bandit attacks have also taken place on IDP camps across northern Nigeria, putting the lives of health workers caring for displaced persons at risk.

Levi Otim, an official at Logo IDP camp in Benue State, north-central Nigeria, says since Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) left the camp early in 2022, no group or agency has been providing healthcare services to the displaced persons, who number over 4,000.

"We do not currently have any health workers catering to the displaced persons here," says Otim, adding that he does know whether insecurity was also a factor for MSF leaving the camp.

However, at the Central Primary School IDP Camp in Gwada, Shiroro Local Government Area of Niger State, which houses more than 1,400 displaced persons, camp official Habibu Musa says the police and vigilantes have been working together to provide security for the camp.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

"Hence, we have health workers from the primary health care centre in the community coming to give routine immunisation to the children. Through the health workers' services, the displaced persons have been faring well. More needs to be done, though, especially with the supply of food and medicines," Musa says.

At the IDP camp in Kumaji, Sokoto State, camp manager Nasiru Muhammed, says the displaced persons feel unsafe anytime they learn about an attack on an IDP camp in the state or any other part of the country. This, he says, may make it difficult for health workers to do their job well.

"Though normalcy seems to be returning unlike what we used to have, there is still a sense of fear when we hear about attacks in other parts of the country. In fact, there are some mothers who refuse to take their children to the health centre for routine immunisation because of fear of the unknown. But, over time, I am hopeful they will change their minds," Muhammed says.

Credit: Jesusegun Alagbe

On March 3, then-president Muhammadu Buhari, promised to end the war against terrorism and other forms of insecurity before leaving office. As of May 29, when he left office after a two-term tenure of eight years, this had not been achieved. His successor, President Bola Tinubu, during his inauguration, highlighted security as one of his top priorities.

Akande, the public health expert, says he hopes the Tinubu administration will not allow insecurity to fester.

"I want to believe that the level of security will improve under the Tinubu administration. Hopefully, he [Tinubu] will not allow this level of insecurity to persist, because as for me, the outgone president did not do enough to tame insecurity," he says.