What do we know about the outbreak of Ebola in Uganda so far?

The outbreak is the first to be caused by the Sudan virus in more than a decade, and efforts are already underway to test whether new candidate vaccines against Ebola Sudan will be protective.

- 3 October 2022

- 7 min read

- by Linda Geddes

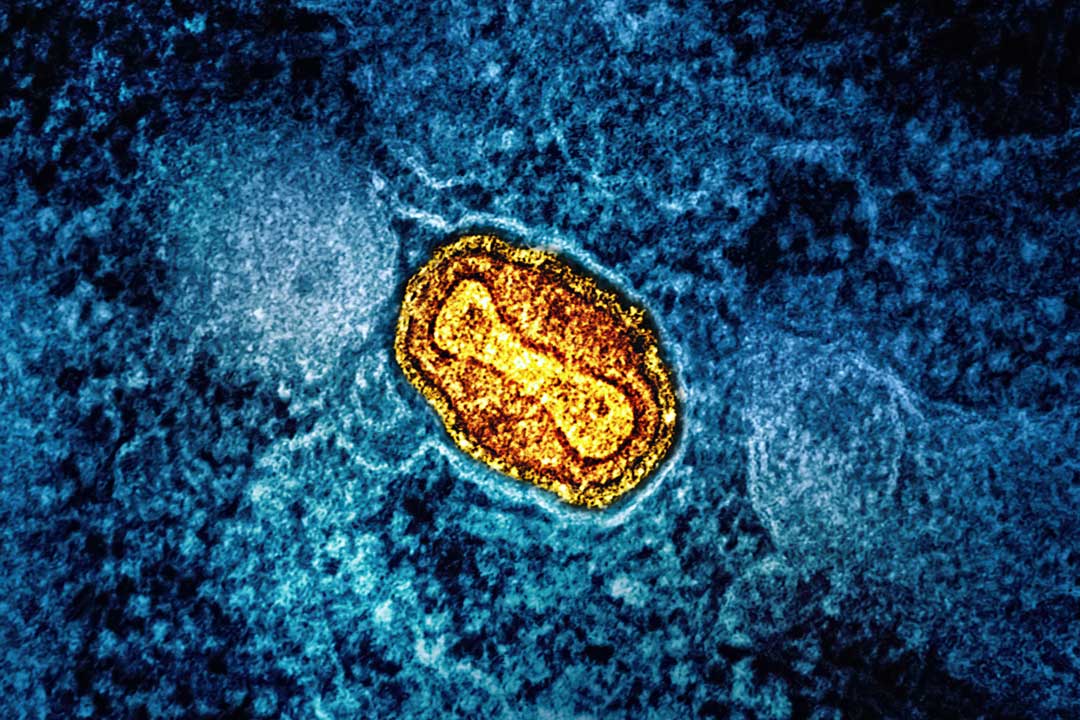

On 11 September 2022, a 24-year-old man from Madudu in central Uganda began feeling feverish and bleeding from his eyes, as well as starting to cough, vomit, and discharge blood-stained diarrhoea. After visiting two private clinics during the next four days, he was referred to hospital and quarantined while blood tests were carried out. On 19 September, PCR tests revealed that he was infected with Sudan virus, one of four viruses known to cause Ebola virus disease in humans. That same day, the man died.

As of 1 October, a total of 41 confirmed and 19 probable cases have been reported, including 24 deaths. Nine of these deaths have been from confirmed cases) and all of them in central Uganda. Here’s what we know about the outbreak so far.

What is Sudan virus?

Ebola was first discovered in 1976, when two independent outbreaks of haemorrhagic fever occurred in central Africa – one near the Ebola River in what was then Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC), the second in what is now South Sudan. Scientists later discovered that these outbreaks were caused by two genetically distinct viruses: Zaire ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus. They have since discovered four further ebolaviruses, two of which can cause human disease (four in total).

The good news is that there are several candidate vaccines against Sudan virus in development.

Since 1976, outbreaks of Sudan virus have emerged periodically, with seven reported until now – four in Uganda (the most recent being in 2012) and three in Sudan. Estimated case fatality rates have ranged from 41% to 100% during these outbreaks.

How does it differ from Zaire ebolavirus?

The Zaire ebolavirus has been responsible for more outbreaks and human cases of Ebola than any other strain, including the 2014–2016 West Africa outbreak and the 2018–2020 outbreak in DRC. Although it is genetically distinct from the Sudan virus, the symptoms they trigger are very similar: fever, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and sore throat, followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, and/or symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function. Some patients may experience both internal and external bleeding (e.g. bleeding from the eyes or gums, or blood in the stools). Both viruses are highly lethal, although current evidence suggests that the case fatality risk is higher following Ebola Zaire infection.

Both viruses are transmitted through direct contact with the blood or body fluids of someone who is infected with or has died from Ebola, objects contaminated with these body fluids, or close contact with infected animals. Incubation periods – the time from infection to the onset of symptoms – range from two to 21 days. Infected people start to spread when they develop symptoms, however diagnosis of Ebola can be difficult because the early symptoms often resemble those of other infectious diseases, such as malaria.

Will existing Ebola vaccines be effective?

So far, two Ebola vaccines have been licensed – both to protect against Zaire ebolavirus – and are prequalified by the WHO. Gavi-funded global stockpiles of one of these vaccines – Merck’s rVSV-ZEBOV (ERVEBO) vaccine – are available to deploy at the earliest sign of an outbreak, but because Zaire ebolavirus is genetically distinct from Sudan virus, available evidence suggests that Merck’s vaccine will not help to curb the current outbreak, should it continue to spread.

“Based on available evidence the ERVEBO vaccine – used in the recent responses against the Ebola virus disease outbreaks – will not provide cross-protection against the Sudan virus disease,” the WHO said.

The other vaccine – Johnson and Johnson’s Zabdeno/Mvabea vaccine – is a two-dose vaccine, with the first dose priming the immune response against the Zaire ebolavirus and the second dose boosting the immune response to Ebola Zaire. The second dose contains additional antigens from other Ebola species, including Sudan species, and might provide protection based on available evidence from a non-human primate model. However, it has not been tested against Sudan virus disease in humans. Also, because the second dose isn’t administered until 56 days after the first, it is not appropriate for outbreak response, the WHO said.

What about other vaccines?

The good news is that there are several candidate vaccines against Sudan virus in development. In addition to the Janssen vaccine, two other vaccines using chimpanzee adenoviruses as vectors have already undergone Phase 1 human trials to determine how much vaccine should be given in a dose, and to confirm that they trigger an immune response and are safe enough to be tested in larger numbers of volunteers.

Have you read?

A clinical trial of one, or possibly two, of these vaccines could start within weeks, provided Uganda agrees, said Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo, head of the WHO’s R&D Blueprint. “We are doing everything that you are supposed to do when you want to get a trial started in a week or two maximum,” she told Stat News.

Furthest along is a vaccine developed by the Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington DC, which uses a chimpanzee adenovirus to deliver the Ebola Sudan glycoprotein to the immune system. Another potential candidate is a human adenovirus-based vaccine being developed by the University of Oxford, UK, designed to present both the Ebola Sudan and Ebola Zaire glycoproteins to the immune system.

If the trial does proceed, it is likely that contacts of known cases would be offered the vaccine and then monitored to see if they developed Ebola virus disease – a strategy known as a ring vaccination. Seth Berkley, Gavi’s CEO, has confirmed that Gavi is ready to assure a market and potentially a global stockpile of any new vaccine should one prove successful in trials.

How worried should people be?

Investigations into the outbreak and the possibility of it spreading widely are ongoing, but at a national level the WHO has assessed the risk of it having a potentially serious public health impact. One issue is that the 24-year-old who died on 19 September may not have been the first human case. The WHO is investigating the possibility that the outbreak started three weeks before he was identified, and not all potential transmission lines have been tracked.

The WHO has said the risk of international spread cannot be ruled out at this stage. However, at a regional level it has assessed the risk to be “moderate” and at global level to be “low”.

Another is that some of the infected individuals visited facilities where inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) was used, while others died and were traditionally buried with large funeral ceremonies. Also, cases were detected among individuals living around an active gold mine, where traders and miners come and go. The declaration of an Ebola outbreak may cause some miners already incubating the virus to flee.

The WHO has said the risk of international spread cannot be ruled out at this stage. However, at a regional level it has assessed the risk to be “moderate” and at global level to be “low”.

What else is being done to stop the outbreak?

The WHO is working closely with Ugandan health officials to roll out control measures, including isolating, testing and treating those who are potentially infected, and tracing their recent contacts. The Ministry of Health is coordinating the response and, with support from partners, engaging with the affected communities to promote behaviours that can reduce the risk of the disease’s spread. The country has experienced outbreaks of Ebola, and other viral haemorrhagic fevers in the past, including a large outbreak of Ebola in 2000.

“Uganda is no stranger to effective Ebola control,” said Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa. “Thanks to its expertise, action has been taken to quickly detect the virus, and we can bank on this knowledge to halt the spread of infections."