What impact does malnutrition have on the effectiveness of vaccination?

Malnutrition can affect the immune system and the quality of immune response to vaccinations, with potential implications for low-income countries where COVID-19 is already fuelling a "hunger pandemic" in the most vulnerable people.

- 2 November 2020

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

Malnutrition contributes to nearly one in two deaths in children younger than five years in low- and middle-income countries, often because they are more prone to infection. In many places without consistent access to nutritious food, malnutrition and infection co-exist in a vicious cycle. Children who are malnourished have poor immune systems and are more vulnerable to disease, which means immunisation is extra important for them.

A 2013 study in Asia, Africa and South America in children under five, showed that the hallmarks of malnourishment - stunting, wasting and underweight - were all linked to a higher risk of death from infections such as meningitis, measles and tuberculosis and sepsis. But because malnutrition can cause immunodeficiency, some scientists have suggested that vaccines may not be as effective as normal at priming their immune systems.

Malnutrition is not only caused by a lack of nutritious food; infectious diseases such as diarrhoea and malaria can cause undernutrition by reducing the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. This is why preventing infectious disease remains important for child health and development.

What happens to the immune system of a malnourished child?

A 2015 study reviewed data on how malnourished children respond to different types of vaccines. Although malnourished children have the same number of white blood cells, they have fewer cells that can present antigens (a molecule on the pathogen that triggers an immune response) to the immune system.

In malnourished children, the mucosal barrier – the layer of mucus in our noses and mouths that stop germs entering our body – is compromised, which is why they are more prone to infection.

Much of the evidence for our understanding of immunity in malnourished children is not as strong as it could be, and uses outdated laboratory techniques or definitions of malnourishment. Which is why looking at studies conducted in mice can offer insights. When mice were fed a low protein diet and infected with influenza, they had a reduced antibody response, which then recovered when they were given a high protein diet. Studies in mice have also shown that malnourishment may cause a shorter-lived immune memory, which could have implications for the effectiveness of vaccines.

How immunisation still gives children a fighting chance

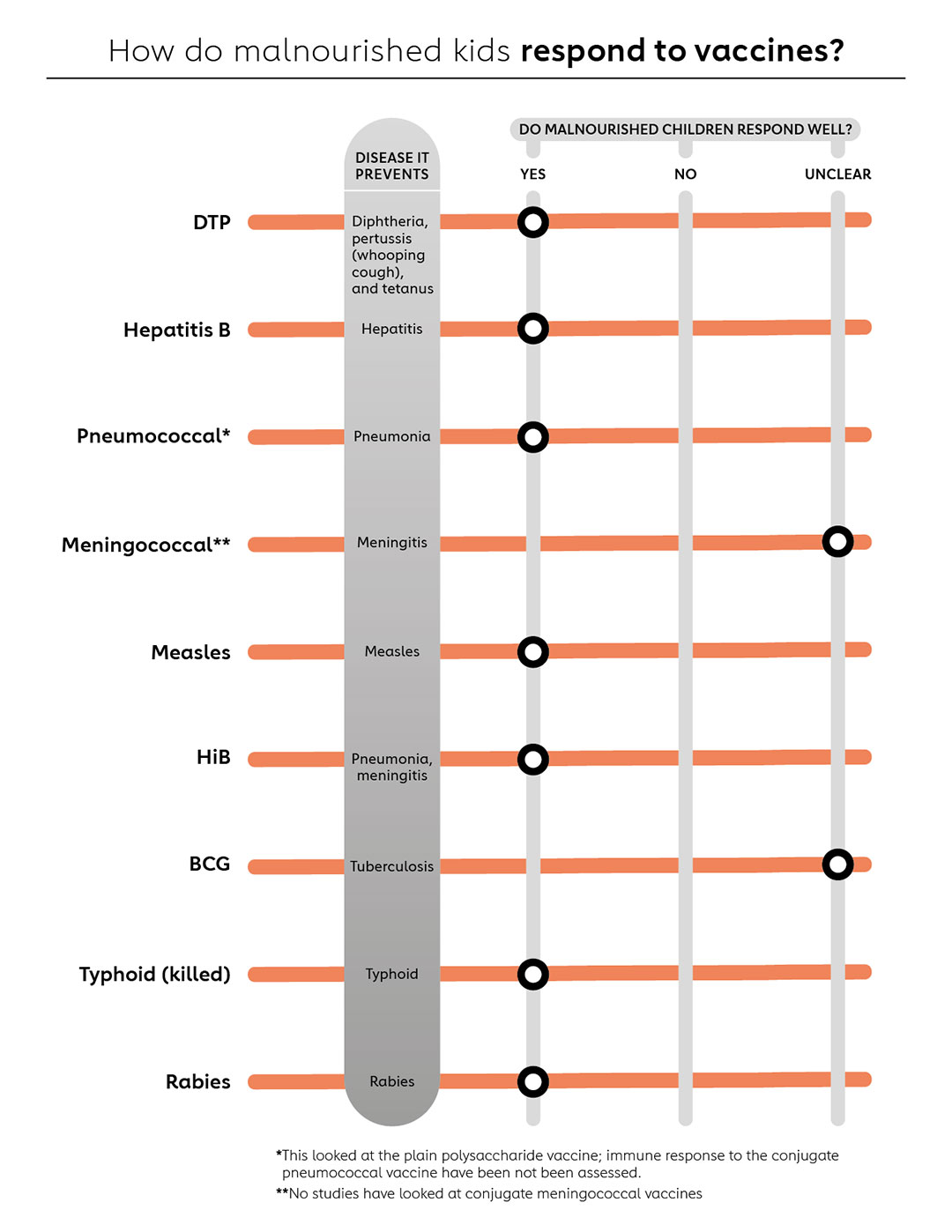

Despite the limitations with the data, the researchers found evidence that malnourished children can generally produce a protective response from a variety of vaccines, although their immune response is sometimes lower than that of well-nourished children (see graphic).

As well as preventing infectious disease, for malnourished children or those at risk, vaccination could also prevent recurrent infections that might exacerbate undernutrition. This has been borne out from research that shows nutrition-specific approaches alone rarely reduce malnourishment – they need to be combined with a package of health support, including immunisation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already disrupted routine immunisation in places where people need it most; given that many of these people are also at risk of hunger and malnutrition, investing in and strengthening immunisation programmes will be vital.