What happens when you don’t recover from Japanese Encephalitis?

As many as 30% of Japanese encephalitis patients are expected to die. Of the survivors, only a third are likely ever to return to full health. The rest live with consequences that range from personality shifts to intellectual disability to seizure disorders; blindness to motor deficits.

- 13 January 2023

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Days into the new year, Australia confirmed its first Japanese Encephalitis (JE) case of the southern summer. This patient is the country's 45th since March of 2022; seven of the 45 have died. As recently as 2021, the viral brain fever was considered foreign to the island country.

Only a third of severe JE disease patients are expected ever to recover completely.

The Australian outbreak offers evidence, scientists say, that with climate change, the range of the mosquito-borne sickness is growing. JE is currently considered an endemic threat to some three billion people living across 24 countries in Asia and the Western Pacific, and estimated to sicken about 68,000 people globally a year, but those figures risk growing as swelling populations and changing weather and land-use patterns make a broader swathe of the world hospitable to the causative Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV).

That's cause for particular concern because only a minority of people who survive severe JE survive it unscathed.

Grim odds

Just one in 250 infections results in serious symptomatic illness, but infection with JE is a gauntlet that nobody wants to run. Between 5-30% of patients – most of whom, globally-speaking, are children – are expected to die. For a large proportion of the survivors, life after JE will be much harder. Broadly, 30-50% will live on with permanent neuropsychiatric 'sequelae,' or conditions resultant from the disease, but in specific outbreaks, the rate of damage can be higher.

A 2017 study from eastern Uttar Pradesh, India, for instance, reported that 74.6% of the sample – children hospitalised with JE at a regional referral hospital – developed 'neurological sequelae at different levels of severity.' An estimated 15.4% of the children died after discharge; 63% lived on with disabilities.

In places with better hospital facilities, the mortality rate does tend to be lower – but cruelly, the number of patients surviving with sequelae is then higher.

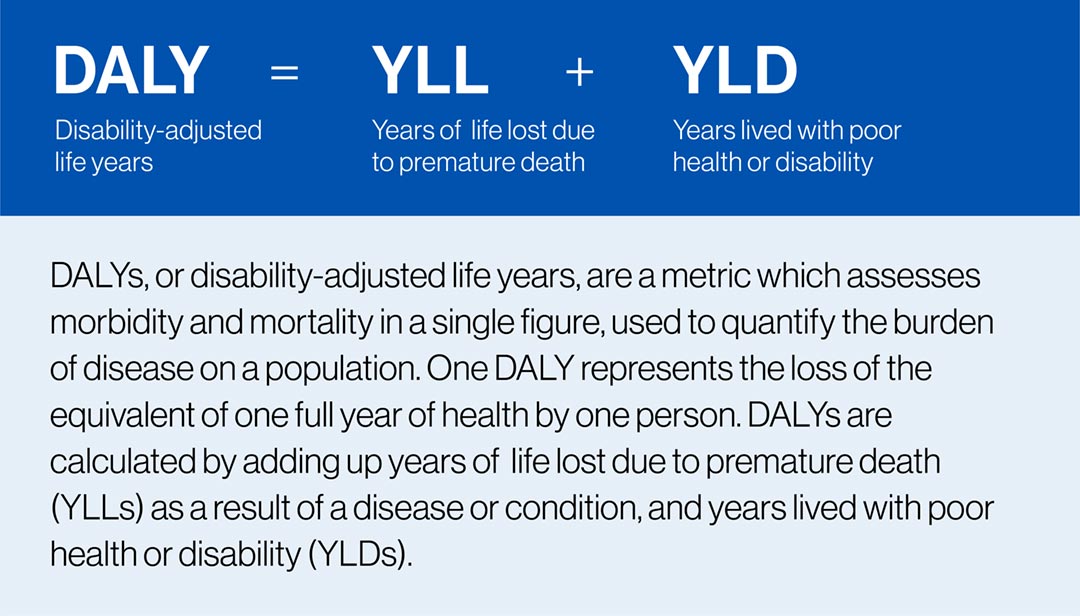

Only a third of severe JE disease patients are expected ever to recover completely. Japanese encephalitis is thought to cost the world 709,000 DALYs (disability-adjusted life years) annually – making it the most damaging, though not the most deadly, human arboviral disease.

What do JE sequelae look like?

JEV attacks the central nervous system and invades the brain, causing swelling, inflammation, and often damage to that most critical, most complex of organs. That means that the nature of the disabilities that result can range from major physical disability all the way to psychiatric changes (in fact, sometimes the clearest symptom of JE is changed behaviour, prompting incorrect diagnoses of mental illness.)

According to a review article published in the British Medical Journal, 30% of people with JE sequelae live with motor deficits, commonly including fixed flexion deformities of the arms and hyperextended legs. Twenty percent have 'severe cognitive and language impairment' – often together with motor issues – and another 20% suffer convulsions. A study from Gansu, China, found neurological deficits in 44.7% of JE patients, including 'subnormal intelligence' – based on IQ – in 21.2% of subjects.

Have you read?

Beyond statistical categories, cases of disability after JE can be strikingly diverse. An NDTV report on disability following JE offers insight, introducing viewers to five-year-old Sabia from Uttar Pradesh who lost his eyesight, and 15-year-old Alok, who has suffered physical and mental deficits that have left him completely dependent on his family for care.

A patient from Wales described in a 2019 study, and who had contracted JE while in China, was still dependent on ventilation two years after illness onset, and was unable to stand up, speaking only in a whisper. Another case study presented in the same paper, a young British woman who fell ill in Thailand in 2014, struggled with severe persistent fatigue two and a half years later.

Often, even people classed as having made a 'good recovery' from JE have actually undergone subtler changes, meaning they live with learning difficulties, behavioural changes, or harder-to-spot neurological shifts. For Australian Garry Taylor, aged 71, "recovery" after a six-week hospitalisation in 2022 means a return to an almost normal life – one in which he struggles with tasks that were easy before JE, like using a computer, or remembering login codes. "You lose a lot," he told 9news.

But we have a vaccine

Sustained and widespread vaccination against the Japanese Encephalitis Virus has been shown to significantly drive down incidence in endemic countries, with first-generation jabs 'effectively eliminating' the disease in Japan, Korea and Taiwan in the 1960s.

A live attenuated vaccine SA 14-14-2 is prequalified by the WHO for use in children and has been shown to have a protective efficacy between 80%-99% with one dose. With Gavi support, millions of kids in lower-income countries are protected against JE each year.

In Australia, limited JE vaccination campaigns rolled out last year in a bid to curb the spreading outbreak, with health authorities prioritising at-risk groups, like people who work at piggeries or pork abattoirs – pigs are a major reservoir for the virus. But, as Krisztian Magori of BMJ's BugBitten blog warned in October, last year's antipodean flooding and associated disease patterns "might be a sign of things to come." He goes on: "Tis will necessitate an even more robust response from public health and veterinary authorities, with a combination of mosquito and viral surveillance, biosecurity and vaccination campaigns, and public outreach and education on mosquito control and personal protection measures."

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you