Vaccine cold chain Q&A

Pfizer and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine candidates have turned the vaccine cold chain into hot news. But what is a cold chain? How does it work? And what does it have to do with equity?

- 29 January 2021

- 6 min read

- by PATH

We spoke with Pat Lennon, cold chain lead with PATH’s Medical Devices and Health Technologies program. He told us what a cold chain is, how it works, and what it has to do with equity.

What is the vaccine cold chain?

A vaccine is, of course, a biological product. If it gets too hot or too cold (some vaccine formulations must be protected from freezing), the active ingredients can degrade and become less effective. Once a dose of vaccine is manufactured, it needs to be transported to immunization programs and clinics and health centers all over the world, and then remain viable until it’s needed.

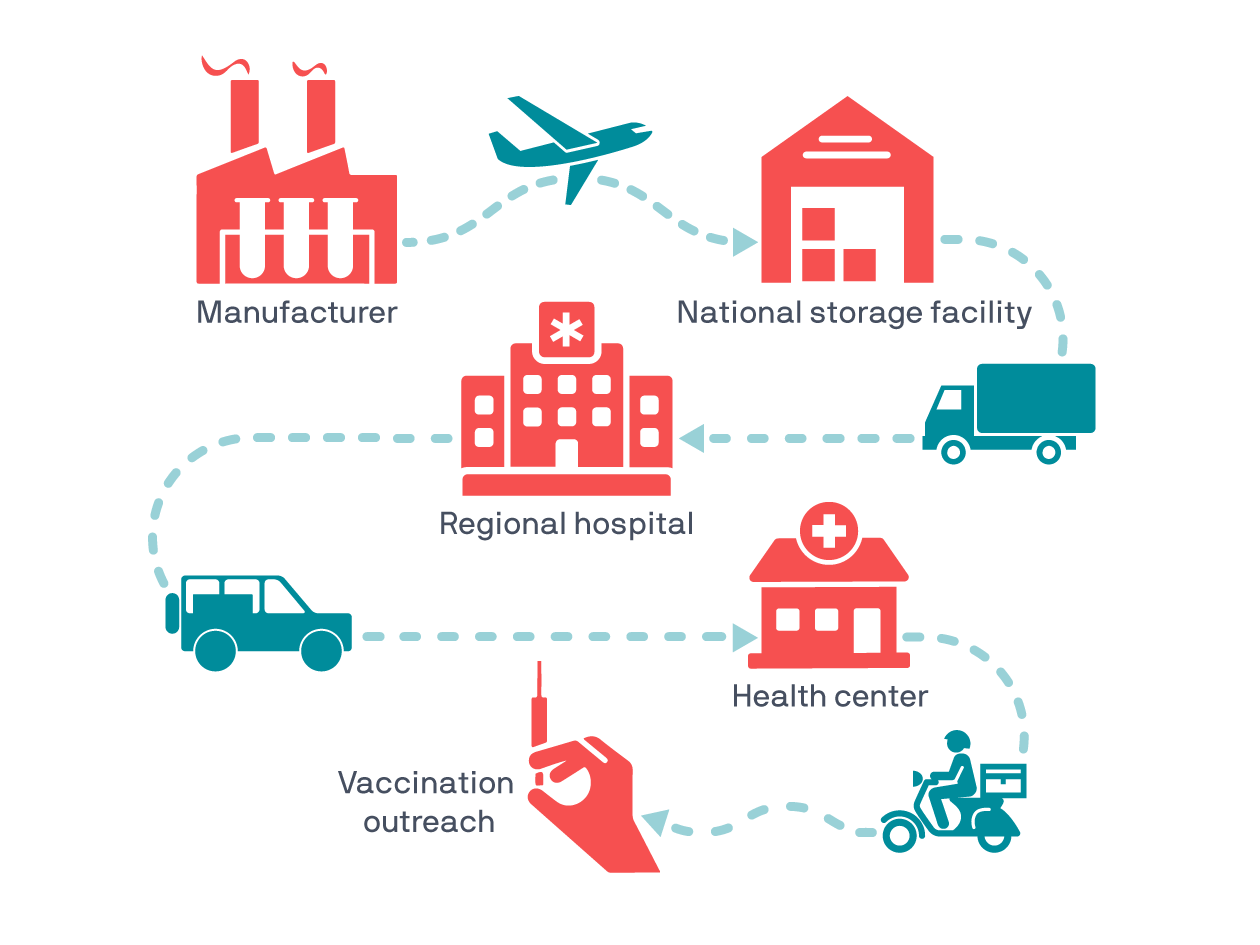

So, the vaccine cold chain is a global network of cold rooms, freezers, refrigerators, cold boxes, and carriers (like the one shown above) that keep vaccines at just the right temperature during each link on the long journey from the manufacturing line to the syringe.

Most vaccines need to be kept cold but not frozen. It sounds simple enough in description but imagine carrying a cool glass of water across a desert—without freezing it, and without it heating up. Needless to say, in practice, the cold chain presents all kinds of challenges, especially when you’re trying to reach remote or rural communities or places where electricity is unreliable.

At PATH, we work to address these challenges by supporting country-led technology integration into health systems and by developing new tools and devices that help extend the cold chain to every community that needs it.

For example, to increase long-term vaccine storage and improve outreach to rural clinics and health centers, PATH evaluates and designs technologies and systems that can extend the cold chain beyond the power grid—like solar-powered refrigerators and new carriers (like the one shown below) that help protect vaccines from excess heat or cold via phase change material.

What does the cold chain have to do with COVID-19?

When vaccines are developed, the first ones to market are almost always less thermostable (meaning they need to be kept much colder to remain effective).

To make a vaccine more thermostable, manufacturers must introduce new elements to the formulation, and that process takes time. They can’t add new elements without testing for safety and efficacy, but once they do, the new formulations can be stored at milder temperatures.

For example, most cold chain vaccines in broad use are stored between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius—about the temperature of a common refrigerator. Some, like Moderna’s COVID-19 candidate or the varicella vaccine for chickenpox must be kept frozen around minus 20 degrees Celsius.

A handful, including Pfizer’s COVID-19 candidate, need to be kept at extremely cold temperatures and require what is called the ultra-cold chain—consistent storage at about minus 75 degrees Celsius (or minus 103 degrees Fahrenheit). Though this significantly increases the challenges associated with distribution, the need for extreme cold in a cutting-edge vaccine isn’t all that surprising.

Have you read?

In the case of COVID-19, where the world needs a new vaccine as fast as possible, thermostability was always going to be an issue for early distribution.

What are some of the challenges associated with cold chain and ultra-cold chain vaccines?

Electricity is a big challenge with either. Refrigerators require a lot of power. Freezers require even more. Ultra-cold freezers in hot places require still more power. Add an unreliable power grid to the mix and generators must be brought in, and the problems continue to compound.

Like electricity, storage capacity is a challenge for all cold chain vaccines but is made harder with ultra-cold formulations—and made completely unprecedented by the demands of COVID-19.

First, the cold-chain storage challenges. Much of the world’s current cold chain capacity is already in use. For COVID-19, we’re talking about adding at least one, if not multiple doses of vaccine for every person on the planet. So far, each of the leading candidates requires two doses—for one, the doses are three weeks apart, for the other, four weeks.

So that’s a time-sensitive doubling of everything—materials, cold chain capacity, logistics coordination, and on and on. And, we need to make sure there is enough capacity to hold all these new COVID-19 vaccine doses without taking space away from the vital vaccines already using the existing cold chain.

“Imagine carrying a cool glass of water across a desert—without freezing it, and without it heating up.”

— Pat Lennon, Medical Devices and Health Technologies, PATH

In the case of the ultra-cold chain, fewer of these vaccines are being used today, but there is also far less capacity and reach. There just aren’t enough freezers that can reach minus 75 degrees Celsius anywhere in the world, let alone in the low-resource settings where PATH works.

That doesn’t mean ultra-cold chain distribution is impossible. The Ebola vaccine also requires ultra-cold chain storage and has been used successfully in several African countries—but there’s an almost unimaginable difference in the scale of those outbreaks and that of COVID-19.

Time is also a big challenge with vaccine distribution. The journey from the factory to the point of care takes months—specifically, an average of four to six. Because of the immediate need for a COVID-19 vaccine, distribution is going to be on a compressed timeline—hopefully down to a month or less. While on the one hand that could mean earlier delivery, it also means far less time for governments to outfit health centers and distribution channels with ultra-cold chain equipment.

Last but not least, is the unprecedented level of collaboration this will all require. The coolers and carriers and cold boxes are the material components of the cold chain. But the cold chain is also a connected chain of people relying on one another—human beings passing buckets in a global fire brigade. In addition to all the technical challenges like storage specifications, we’re going to have to work together like we never have before.

What does all this have to do with health equity?

It’s extremely important that when a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, everyone on Earth is able to access it. Like any health innovation, it does no good unless it can reach the people who need it. And in the case of a pandemic, everyone needs it—the challenges of COVID-19 won’t go away unless they go away everywhere.

Part of PATH’s work pursuing health equity is trying to ensure that advances in health benefit everyone. To accomplish that, we’re always thinking about what’s next—how can we make a device more affordable or work with unreliable power? Or in the case of a COVID-19 vaccine, how can we help distribute it?

As we’ve outlined in this article, there are lots of challenges in getting a vaccine from point A to point B, and these challenges aren’t new. There are dozens of lifesaving vaccines in the world that don’t consistently reach the people who need them—especially people living in remote or rural places all over the world.

Solving that problem is the crux of our work in vaccine innovation at PATH. Sometimes our solutions take the form of thermostable vaccine formulations, new health policies, or innovative devices. And sometimes they take form of multilateral efforts like COVAX—which PATH is proud to support.