A third of babies born to Zika-infected mothers developed abnormalities

An analysis of 13 studies has provided the clearest assessment yet of the risks associated with Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

- 2 December 2022

- 4 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Approximately one third of children who were exposed to Zika virus before birth developed neurological impairments or microcephaly – where a baby's head is much smaller than average – during their first years of life. The research, based on an analysis of 13 studies conducted during the 2015 to 2017 Zika epidemic in Brazil, provides the clearest evidence yet of the scale of the impact associated with Zika infection during pregnancy.

“The findings underscore the continued need to develop a safe and effective vaccine for preventing Zika virus infections during pregnancy,”

"The findings underscore the continued need to develop a safe and effective vaccine for preventing Zika virus infections during pregnancy," said Dr Elizabeth Brickley, Associate Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), and a co-author on the study. "While gaps in population level immunity to the virus persist, the threat of a Zika virus re-emergence remains a concern for public health."

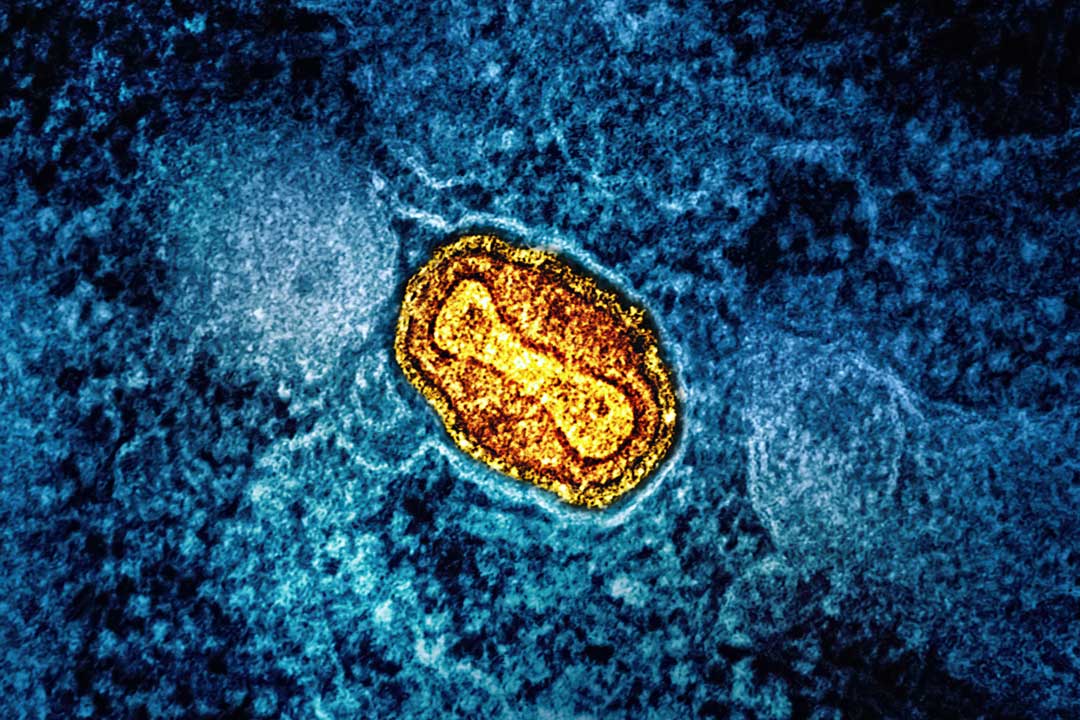

Zika virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes and can trigger symptoms such as a rash, fever, conjunctivitis, muscle and joint pain, headache or a general feeling of being unwell (malaise). Most people develop no symptoms, however.

Since 2007, there have been several large outbreaks, including the 2015-17 Zika epidemic in Brazil, during which around 1.5 million people are estimated to have been infected. Cases were also detected in other parts of South and North America, as well as several islands in the Pacific.

In October 2015, Brazil reported a link between Zika virus infection during pregnancy and infant microcephaly. Since then, researchers have identified other potential impairments associated with Zika exposure, but these studies have generally been small, making it difficult to assess the true nature of the risk, including the prognosis of affected children.

The new study analysed data on children born to 1,548 pregnant women from 13 studies in the Zika Brazilian Cohorts Consortium, where prenatal infection was confirmed through laboratory testing. The consortium was set up to establish the absolute risk of birth defects or abnormalities associated with Zika virus by bringing together data from studies that tracked pregnant women who developed rashes, or children born with microcephaly and/or other potential manifestations of exposure to the virus.

The research, published in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas,found thatapproximately one third of children born to Zika-infected mothers presented with at least one abnormality compatible with exposure to Zika virus before birth. The most common manifestations included neurological impairments, such as seizures or problems with moving or swallowing, brain imaging abnormalities, altered hearing and vision, and microcephaly. Such abnormalities were more likely to occur in isolation, rather than children presenting with multiple abnormalities.

Have you read?

Approximately 2.6% of children born to Zika-infected mothers had microcephaly at birth or when first assessed, rising to 4% across the early preschool years. Babies with microcephaly often have smaller brains that may not have developed properly. This risk appeared to be relatively consistent across different areas of Brazil and socioeconomic conditions.

"These results highlight the importance of having multi-disciplinary health teams available near the time of birth to evaluate children with prenatal exposure to Zika virus exposure and to refer them, as needed, to specialised follow-up care that can provide support for known disabilities and diagnosis of late manifestations," said the study's lead author, Professor Ricardo Arraes de Alencar Ximenes from the Federal University of Pernambuco in Brazil.

Further studies are needed to better understand the risks that such children may face as they grow other older, including their risk of hospitalisation or death at different ages, or alterations in their ability to move, learn new things, or interact with others socially and emotionally.

"Looking forward, the potential re-emergence of Zika virus remains a concern, owing to the lack of an approved vaccine, the growing proportion of the population that is susceptible to Zika virus infection and the potential for new Zika virus strains to evolve with enhanced transmissibility and/or virulence, particularly during pregnancy," the researchers wrote.

"Efforts toward developing affordable and accurate Zika virus diagnostic and screening tests remain critically important. Their use for early detection of circulating Zika virus in communities would enable rapid deployment of public health measures for averting new epidemics and would thus minimise the risks of infections during pregnancy and of preventable developmental disabilities in infants."

More from Linda Geddes

Recommended for you