Stopping cholera before it can start: vaccines reach South Sudan’s flood-hit IDP camps

To pre-empt potential cholera outbreaks due to flooding, Unity State in South Sudan has vaccinated 200,000 people.

- 13 April 2022

- 4 min read

- by Winnie Cirino

In late 2021, more than 200,000 people were displaced by floods in Unity State, South Sudan.

As a result, in early 2022 the State Ministry of Health, in partnership with WHO, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and other partners, undertook an emergency cholera vaccination campaign among Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in the two towns of Rubkona and Bentiu.

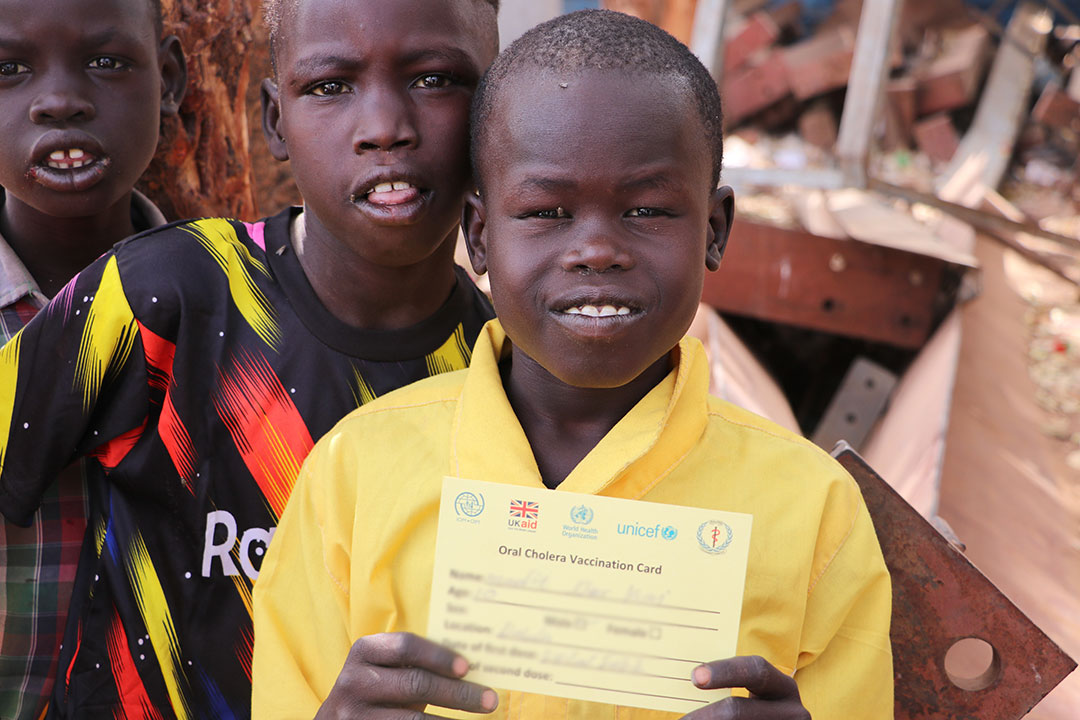

“The health workers told me that the vaccine will protect me and my family from cholera and that is why I took it. I don’t want to get cholera. It is so painful seeing people suffering from it. I am happy that I took it.”

Photo credit: WHO

Dr Duol Biem Kueiguong, Director General of the Ministry of Health in Unity State, says that the campaign, using doses funded by Gavi, was designed to prevent cholera outbreaks in the congested camps.

“Those displaced by the floods are living under harsh conditions. There is very poor sanitation and conditions are unhygienic. Most of the IDP camps around the two towns do not have proper latrines, so there is a very high chance of disease outbreaks. We responded by having the [vaccination] campaign to prevent a cholera outbreak. We targeted over 200,000 people, out of which 177,000 people were vaccinated, which is a high percentage,” says Dr Kueiguong.

The flooding in Unity State is said to be the worst in 60 years. Dr Kuieguong says that the water levels are still high and with more rain expected in the next two to three months, there is the potential for more people to be displaced to the IDP camps.

Photo credit: WHO

“If more displacement happens, the continued poor sanitation increases the likelihood of a cholera. This campaign is, therefore, very important because it will potentially reduce or mitigate the effects of a cholera outbreak if it happens in the near future. A good number of people, having received the first dose of the cholera vaccine, should have sufficient immunity in the lead up to the second round of the OPV campaign,” adds Dr Kueiguong.

Dr Abraham Abednego, the Infectious Hazards Officer in the Emergence Dependence Response Cluster of the World Health Organization says that communication was a central part of the campaign.

Have you read?

“There was some hesitancy from the population. There was also the impression, in some quarters, that the vaccine is for only children and not adults. We addressed the misconceptions via social publications and community engagement,” explains Dr Abednego.

Photo credit: WHO

According to Dr Abednego, cholera vaccines were last administered in Bentiu around 2019, which means the immunity of those who took it has since reduced.

“People are exposed to high risks, and the living standards are poor because the people are in close proximity to each other. There is a lot of poor sanitation and once the rain starts, there is potential for a lot of cases to be reported but, with vaccination, we are protecting the community,” says Abednego.

Cholera cases were reported in parts of Unity State in 2016 and 2017, but no case has been reported in the years since.

Photo credit: WHO

Dr Abednego says that there were reports of severe diarrhoea reported but, so far, samples collected and tested have been found to be negative.

“This vaccination campaign provides very good protection to the vulnerable population and also bridges the gap to long term interventions like proper water systems, proper hygiene and sanitation,” Dr Abednego says.

Ngor Dok took the cholera vaccine in January when it was brought to Bentiu. He says that he is happy the vaccine was brought to the IDP camp.

“The health workers told me that the vaccine will protect me and my family from cholera and that is why I took it. I don’t want to get cholera. It is so painful seeing people suffering from it. I am happy that I took it,” he says.

Dr Abednego advises the public to take the cholera vaccine, emphasising that it is safe and effective for everyone from one year old and above.

A total of 686,000 oral cholera vaccines were provided to Rubkona from the Gavi-funded global vaccine stockpile, with a target population of 343,000 people across the region.

Gavi started funding the global cholera vaccine stockpile in 2013. Since the stockpile was launched, millions of doses every year have helped tackle outbreaks across the globe. In the 15 years between 1997 and 2012, just 1.5 million doses of oral cholera vaccine were used worldwide. In 2021 alone, the stockpile provided 29 million doses for emergency and preventive use across the globe.