Sri Lanka was winning its battle with leprosy. Then came COVID-19

Slowly, but hidden behind the disruptive pandemic virus, leprosy was spreading. Now Sri Lanka’s health department is working hard to find and cure a cohort of patients before it’s too late.

- 1 March 2023

- 6 min read

- by Aanya Wipulasena

The doctor confirmed it was leprosy, news that seemed hard to compute. “I started crying,” Susanthi Palihawadana recalled. Just months before her diagnosis, Palihawadana, from Slave Island, a Colombo suburb, had given birth to her third daughter.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is one of the world’s oldest and most stigmatised diseases. Left to progress unchecked, it can lead to life-altering deformity and disability.

“It helps for people to hear about leprosy from someone who actually had it. I am always willing to share my knowledge and experience with others. Sadly, this disease is still stigmatised in our society."

– Susanthi Palihawadana

Credit: Aanya Wipulasena

But today, doctors also understand it as a slow-moving, slow-spreading bacterial infection that is curable and controllable with the timely detection and medical care.

“I have heard stories of leprosy patients, how they were treated and how they are kept in enclosures with only a small window to give food and water,” Palihawadana, now 60 years old, remembered.

When the doctor prescribed her a course of medication, cautioned her to take the blister-packaged pills without fail, and told her to go home, she was surprised. She was expecting to be placed in isolation, too.

Her family and close contacts were soon screened. No one else had it. Today, Palihawadana is cured of the infection and disability-free.

Cases undetected

That should be every leprosy patient’s story. The modern treatment – a combination course of three drugs, taken in pill form for either six months or a year, depending on the intensity of infection – is simple and effective. Taken early enough, it heads off the nerve damage that can lead to life-long disability.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted Sri Lanka’s fight to eliminate leprosy , giving rise to concerns that thousands are being left undiagnosed and therefore untreated.

According to statistics by the Anti-Leprosy Campaign under the country’s Ministry of Health (MOH), more than 1,300 new cases were reported in 2022, with 10.6% of the patients being children. The number of cases for the year 2021 was 1,026 and in 2020, 1,213. The number of cases in 2015 was nearly 2,000.

“COVID-19 and the shortage of fuel that followed affected the detection of cases in 2020, 2021, and early 2022. Now there are undiagnosed patients in the field,” Dr Dilini Wijesekara, Consultant Community Physician at the Anti-Leprosy Campaign said.

Credit: Aanya Wipulasena

She said several projects were kicked off last year and will soon be rolled out to encourage patients to seek medical attention as soon as they spot early symptoms like skin patches and growths.

Have you read?

“The message we are giving people is that leprosy is curable. A week after starting medication the patient will not spread it to another person. So, it is vital that they seek treatment as early as possible,” Dr Wijesekara said.

Sri Lanka’s leprosy journey

In 1901, Sri Lanka – then Ceylon, a British colony – enacted a law called the Leper’s Ordinance to try and control the then-incurable, crippling sickness. The law, now in disuse, called for the segregation of leprosy patients. Patients were left in isolated enclosures and some were even sent to an island out of sight of everyone else.

With the introduction of multi-drug therapy (MDT) in the 1980s, leprosy was looked at in a new light. The disease was treated successfully in the island nation. In 1995, Sri Lanka achieved the Leprosy Elimination Target set by the World Health Organization (WHO), which meant that the crippling sickness was formally considered to no longer present a public health problem in the country.

Two teledramas that addressed the stigmatisation of leprosy and patients have helped to encourage patients to seek treatment. Reflecting on past success, the Anti-Leprosy Campaign launched a social marketing campaign named ‘LIFE Sri Lanka’ (Leprosy Initiative For Elimination) last year to spread information regarding the disease on social media.

“In addition, we will soon distribute a pictogram in schools this year. The idea is to create awareness amongst parents and guardians so that they can check if their children have signs of leprosy,” Dr Wijesekara said.

A new strategy

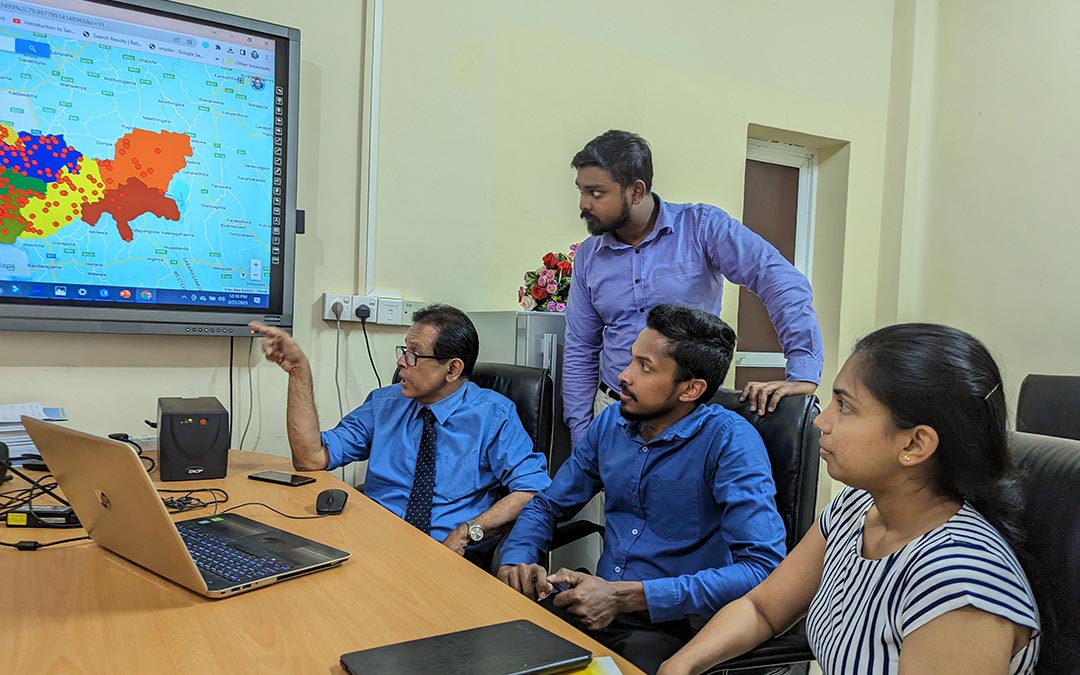

Sri Lanka’s latest strategy in its journey to eliminate leprosy is the adoption of a Geological Information System (GIS) to locate high-risk areas and conduct health screenings in these areas.

The Anti-Leprosy Campaign is using data from the past decade to create the GIS with the aid of a group of undergraduates from the University of Sabaragamuwa.

“From 2020 to 2022 we have missed around 3,272 cases. From January this year, we started using GIS to identify high-risk areas,” director of the Anti-Leprosy Campaign Dr Prasad Ranaweera said.

Credit: Aanya Wipulasena

The map has clear indications of where previous patients live. On the map, dark green areas indicate leprosy-eliminated areas, light green indicates zones where both child and adult leprosy transmission have been interrupted, and orange indicates regions where only child leprosy transmission has been interrupted. Red marks zones with likely active transmission among both children and adults.

“We will concentrate activities in target areas. With the GIS it is easy to focus activities depending on the risk, and use resources in these areas effectively,” Dr Ranaweera further explained.

From school to school and child to child

In his message for World Leprosy Day this year, Yohei Sasakawa, WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, said that if everyone learns facts about the disease and shares knowledge it can help to create a “world free of problems associated with the disease”.

The Colombo Municipal Council area of Sri Lanka is a hotspot for the spread of infectious diseases generally. This is because of its high-density population, and because thousands travel to and from the area for work and school. Therefore, the task in Public Health Officer NP Gamini Wimalaratne’s hands is crucial. He and his team conduct workshops in schools to create awareness of leprosy.

Credit: Aanya Wipulasena

“We make it as interactive as possible so that both children and parents or guardians will learn and even feel comfortable to share information of possible infections with us,” he said.

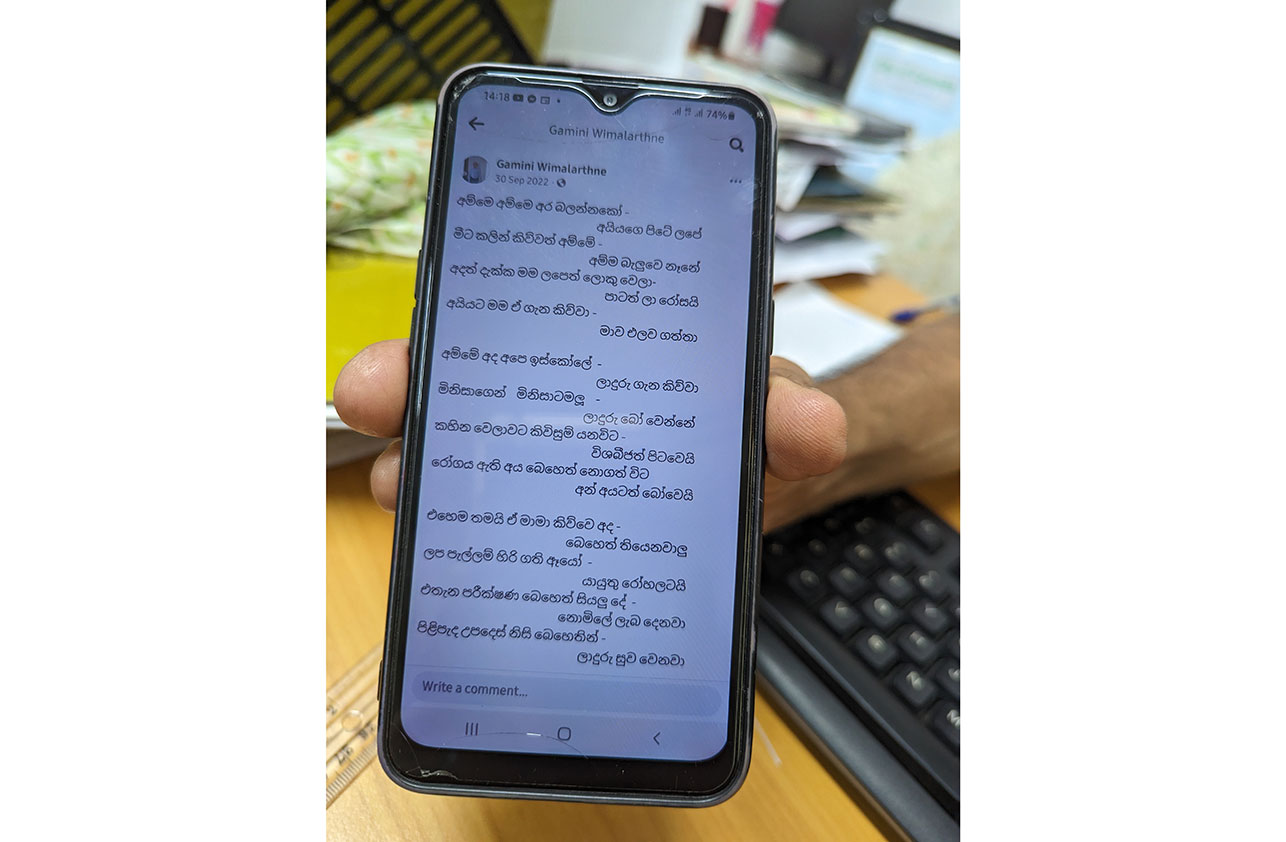

Gamini also incorporates his various talents to make learning more fun. He has written poems, created posters, and even written a song about leprosy. “I am planning to get the song recorded,” he said.

Credit: Aanya Wipulasena

Sometimes, Gamini invites survivor Palihawadana to attend his awareness programmes to talk about her experience.

“It helps for people to hear about leprosy from someone who actually had it. I am always willing to share my knowledge and experience with others. Sadly, this disease is still stigmatised in our society. I do what I can to help people see the truth,” Palihawadana said.

More from Aanya Wipulasena

Recommended for you