Vaccine profiles: Tetanus

The disease can kill one in five people infected, yet an effective vaccine exists. Routine tetanus immunisation saves the lives of thousands of newborns every year.

- 27 October 2021

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

First your heart might start racing, and your temperature soars as you start to sweat. Then your muscles start to spasm; by the time your jaw muscles tighten up to create ‘lockjaw’, you know without doubt you are infected with tetanus.

The disease kills around 10-20% of everyone it infects. The work of the EPI and organisations like Gavi has helped to widen vaccine coverage around the world, bringing the annual death toll down from more than 300,000 in 1990 to around 15,000 in 2018.

If you were unfortunate enough to become infected with tetanus in ancient Greece, you might have been treated as Hippocrates is supposed to have advised, with a prescription to drink wine and be wrapped in oil-soaked clothes. Unluckier still were those who were suspected of being infected during the Renaissance,` when the cure was to be covered in manure. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that a bacterium was found to be the cause of tetanus and another half century before a vaccine was developed.

Tetanus is rarely a problem in Western countries – in 2019 there were only four cases in England, for example – because the tetanus vaccine is given as part of routine childhood immunisation. Although cases of tetanus have steadily fallen over the past few decades, with a 96% reduction in the number of newborns who die of the disease, it remains a problem in countries where immunisation coverage is low and unsanitary birth practices remain, such as nonsterile instruments being used to cut the umbilical cord.

A bacterium found everywhere

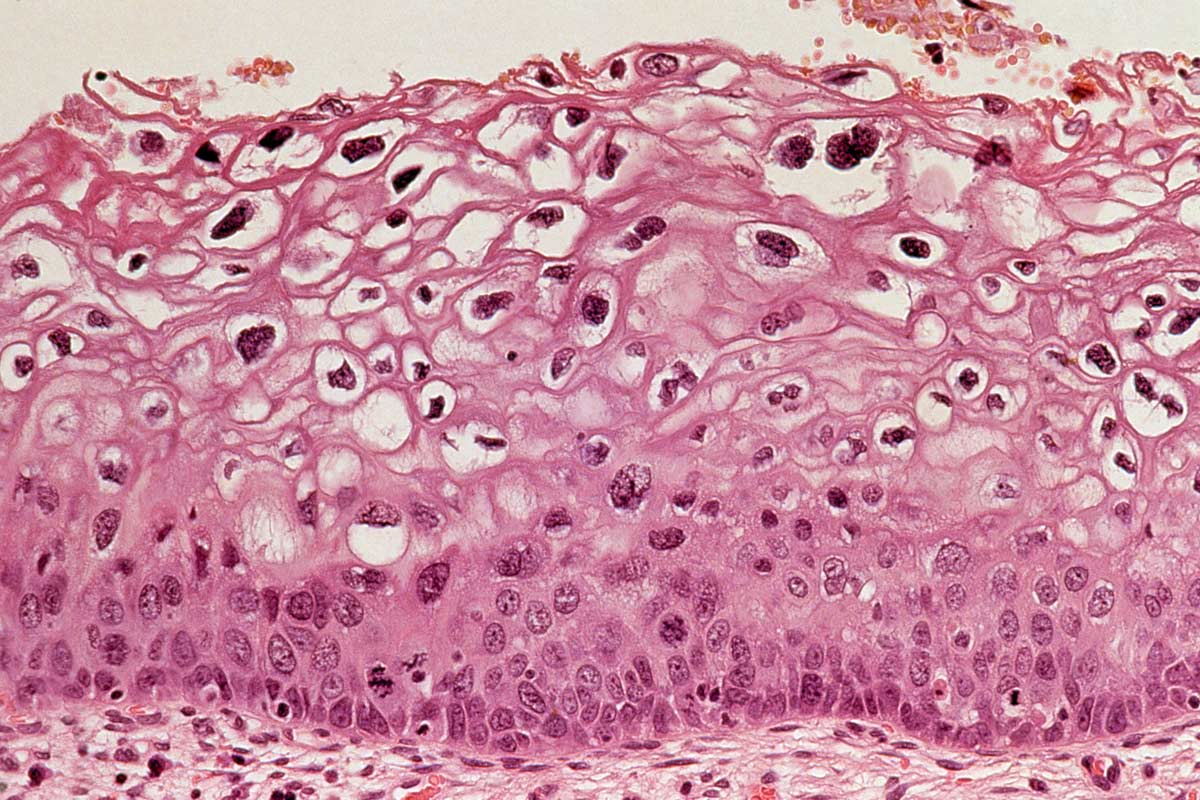

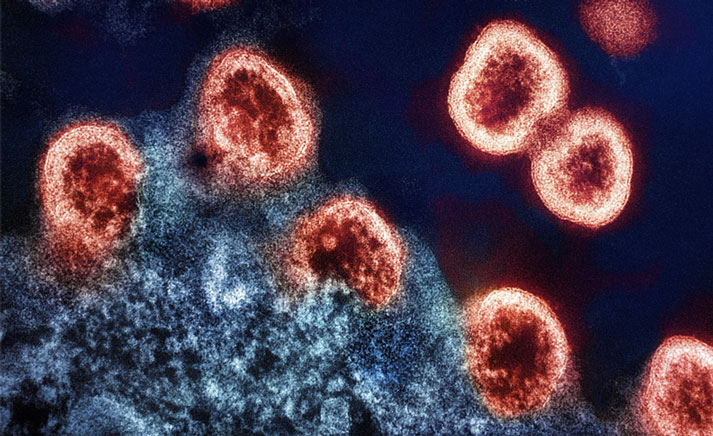

Tetanus is caused by a bacterium called Clostridium tetani, though it is the toxins produced by C. tetani rather than the bacterium itself that causes the disease. Spores of the bacterium are found in almost every environment, especially in organic soil, animal and human faeces, and on rusty tools like nails, needles, and barbed wire. When the bacterium is in spore form it can be fairly indestructible and is resistant to both heat and most antiseptics. People can become infected through cuts, burns or wounds.

Have you read?

Once the bacterium is in the body, it releases toxins that travel to the central nervous system, blocking the nerve signals from the spinal cord to the muscles. This triggers symptoms that include muscle spasms strong enough to break bone.

This can cause the jaw to become frozen in place, which led to tetanus being colloquially called ‘lockjaw’. Other symptoms include difficulty in swallowing, seizures, headaches and fever. Symptoms normally appear around 14 days after infection, though this can vary from 3 to 21 days. Because the symptoms are so distinctive, tetanus can be diagnosed without laboratory tests.

Tetanus doesn’t spread from person to person, except in the case of pregnancy, where an infected, unvaccinated mother can pass on the infection to her baby.

Vaccine development

The protective effect of tetanus antitoxin in preventing infection was discovered in the 1890s. By the first world war, wounded soldiers were being treated with antiserum harvested from horses. By the second world war, a vaccine with tetanus toxoid, an inactivated form of the toxin, had been developed and was given as routine immunisation.

Vaccines against diphtheria and pertussis had also been developed by then, and in 1948 tetanus began to be given in combination as DTP (Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis). It’s recommended to be given to babies at 2, 4, 6, and 18 months of age and then again at 4 to 6 years old, followed by a booster dose every 10 years. Pregnant women should be vaccinated between 27 and 36 weeks of pregnancy.

The Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was established in 1974 to widen access to critical vaccines, and tetanus was considered one of the key diseases to protect against. DTP3 coverage measures the percent of one-year-olds who have received three doses of the combined vaccine in a year.

Continued threat

The disease kills around 10-20% of everyone it infects. The work of the EPI and organisations like Gavi has helped to widen vaccine coverage around the world, bringing the annual death toll down from more than 300,000 in 1990 to around 15,000 in 2018. More than a third of these deaths (around 20,000) were in newborn babies, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Global DTP coverage in 2020 was 83%, compared to 75% in 1990.