Pandemic Culture: Protesting the travel bug in Hamburg

Hamburg street artist and former immunologist Lapiz set out to critique his fellow citizens’ rush to jump on planes after getting vaccinated. So why did the travel agency he’d chosen as his canvas thank him for it?

- 15 July 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

In the drab, cold, early months of 2021, when Germany’s pandemic was arriving at its first anniversary, the Hamburg street artist known as Lapiz went to see an osteopath about his tennis elbow. Like pretty much everybody else in the world, the osteopath was fed up. Unlike most other people, she was also already vaccinated against COVID-19. “She said, ’I’m going to Sri Lanka’,” Lapiz recalls. “I’ll do some yoga; I’ll go in the ocean.” Lapiz was perplexed: “I thought, this is so ridiculous.”

The osteopath’s vacation plans weren’t the first signs of what Lapiz describes as a kind of breakdown of empathy, but the encounter hardened his misgivings. The arrival of the vaccine had seemed to atomise global fortunes, he thought: immunisation was being treated as an individual exit ramp from what he knew for sure was a collective predicament.

“What this picture is about is unfair vaccine distribution and a virus happy to travel.”

“In Germany people now think if you’re vaccinated, you’re safe. But if everyone doesn’t get vaccinated, then everyone is at risk – forever,” he told me in May, a while before the spread of the Delta variant had begun to nudge European infection rates upwards again. He imagined the osteopath arriving in Sri Lanka, and meeting someone with a new mutation - “then you’re done,” he warned. “Then it’s just one mutation after another.”

If Lapiz sounds pessimistic – and he admits to being the “naysayer” of his friendship circle – there’s a decent chance that it’s because he knows more than you do. Before he was a street artist, Lapiz was an immunologist. He did graduate work on HIV in new-borns in South Africa, wrote a PhD thesis on animal tuberculosis in New Zealand, and had made it as far as a post-doctoral research position in Argentina when the economy collapsed, his work stalled, and he began to realise that a career in science wasn’t for him. He had been drawn to immunology in part by the vast egalitarian promise of vaccines, he says – but amid the grind of it, he had stopped being able to find that meaning.

Have you read?

Street art offered a direct, democratic outlet for his impatient conscience. “I can’t just do a beautiful face or a colourful bird. It’s beautiful that people do that,” he says, “but I don’t want to do that at all.”

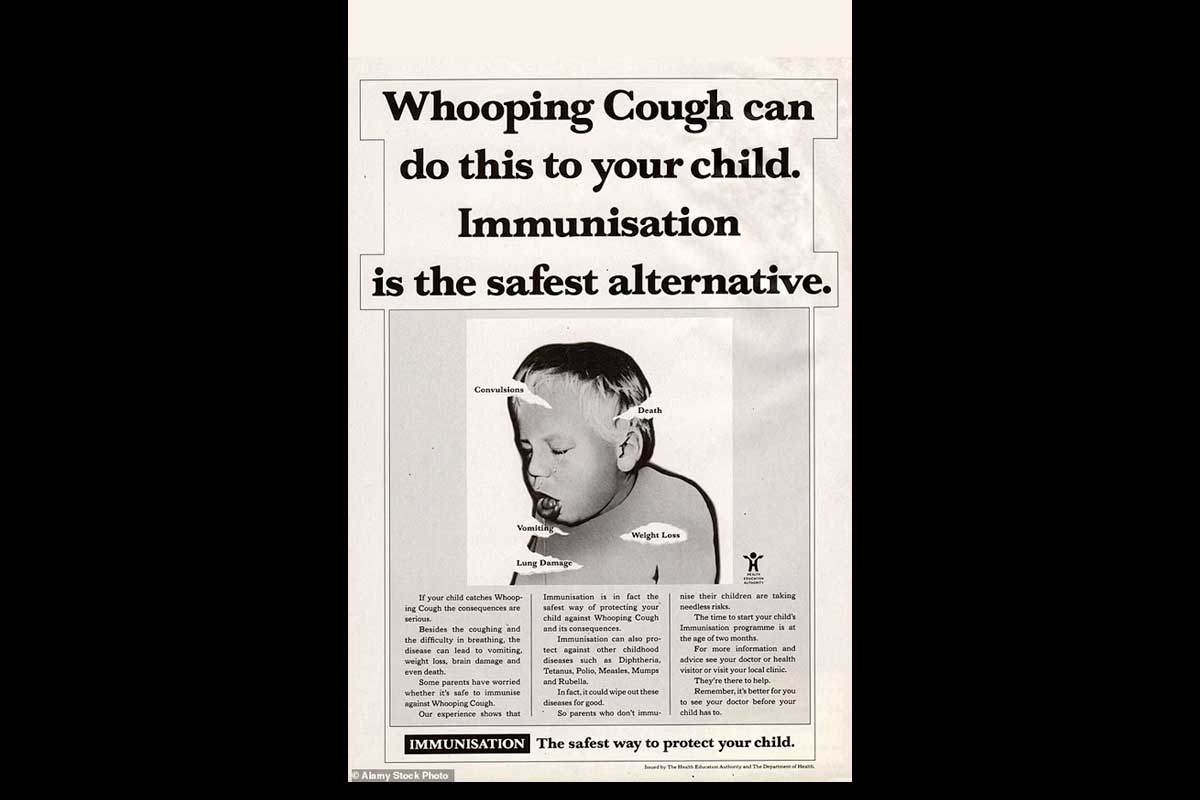

Not long after Lapiz’s visit to the osteopath, a new mural appeared on the street-facing wall of a travel agent in Hamburg’s Sankt Pauli district. The piece, which stands about 1 metre 30 centimetres high, depicts a tourist, post-jab band-aid marking his upper arm, awkwardly contrapposto alongside his purple roll-along suitcase, paunchy in a loud yellow t-shirt and yellow hat. The man’s hat-band is stamped “Reisefieber”, a word which literally translates to “travel-fever,” and means something similar to another German import, “wanderlust”, but more fervid, more pathological.

There is something aggressive about the forward set of the traveller’s jaw. The flag-stickers on his luggage read, at first, like destinations. Look again, Lapiz would tell you, because they should prick like an accusation: Thailand, Vietnam, Brazil, South Africa, Cuba, Nigeria. Left-behind countries, Lapiz says. Countries with low rates of vaccination and persistently vulnerable populations.

The yellow of the figure’s clothes is the yellow of the Impfpass: the international certificate of childhood immunisation. Lately, we agree, amid widespread discussion of ‘vaccine passports’, it’s been easier to see such records not just as evidence of protection but multipliers of privilege. To that point, Lapiz adds, the colour also recalls yellow fever – a disease which, to him, exemplifies the cruelty of global health inequity. A deadly viral infection that was once epidemic in the United States, yellow fever became vaccine-preventable as long ago as the 1930s. But today, Lapiz points out, it remains endemic in poorer countries – countries to which citizens of wealthy countries typically travel safely, vaccine-protected. “Yellow fever for me is a neglected disease like I think corona will become,” he says.

When Lapiz pasted up Reisefieber in his wealthy European hometown, he was levying a charge of complicity. Imagine the artist’s surprise when, the very next day, he received a heartfelt email of thanks from the travel agent whose store-front he had postered. On the one hand, Lapiz was relieved – he’s not in the habit of furtive night-time art-making, more typically being invited to paint public murals in broad daylight, and it he had been feeling mildly paranoid about a possible backlash. On the other, he was a little frustrated. “People saw Reisefieber and just saw what they’d like to do,” he says. Instagram street-art hunters posted images of the work: “they all interpreted it as: ‘now we can finally go travelling’,” he explains. He found it staggering that nobody could see that his “Frankenstein” – the tourist was collaged together out of unflattering found imagery – was satirical. He made an online “exhibition catalogue”, a sort of walking tour of his public works, and spelled it out:

“What this picture is about is unfair vaccine distribution and a virus happy to travel.”