The long haulers: what we now know about Long COVID

Long after the initial infection, millions continue to suffer the crushing fatigue, muscle, joint pain and breathlessness that Long COVID can bring – here’s what we know two years after the pandemic started.

- 3 March 2022

- 6 min read

- by Priya Joi

When Paul Garner first got COVID-19 in March 2020 he thought he was dying. He described feeling “absolutely dreadful, sweaty, dizzy… It was very intense fatigue.” But the intensity of the illness would oscillate wildly. “I would feel better and the illness would come out of nowhere and floor me. It was like being hit over the head with a cricket bat.”

Persistent fatigue and cognitive impairment could be explained by damage to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, cerebral microvascular injury or damage to the prefrontal cortex that has now been documented in COVID-19 patients.

Garner, an infectious-disease researcher at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK, became one of millions who developed Long COVID, a postviral condition in which people report symptoms that persist long after the initial infection seems to have cleared.

Estimating the numbers of people with Long COVID is tricky, and has been put at 10-30% of those that contract the disease. A meta-analysis published this month suggests that about a third of people experience persistent fatigue. A US study from October 2021 estimates an even higher number, suggesting that half of those infected with SARS-CoV-2 will experience Long COVID symptoms up to six months after recovering from the initial infection. At this point in time, there could be as many as 220 million people suffering with the condition.

Defining the condition

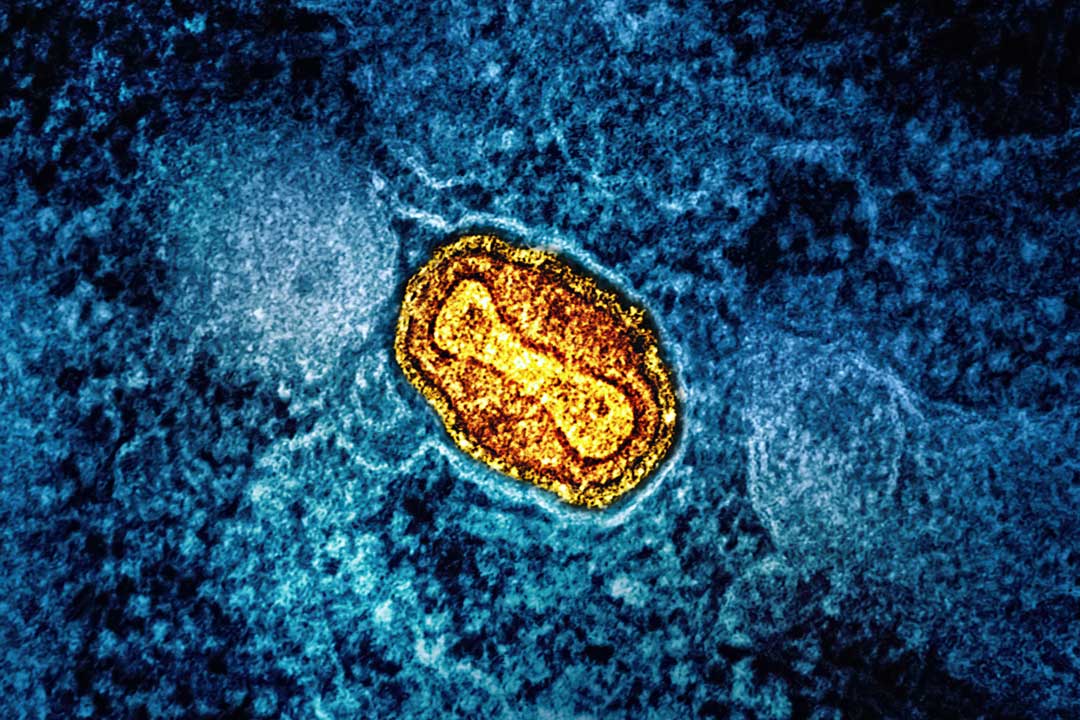

Chronic post-viral conditions have already been seen with another coronavirus that caused a pandemic, SARS or severe acute respiratory syndrome. This emerged in 2003, although a lack of understanding of the biological mechanisms behind it means they have not been studied as much as they should have been. A study in Hong Kong showed that around one in five people who had SARS were still not able to return to normal life, including work, a year after their first infection.

For 18 months, there was no clear definition of a condition that had such a broad array of symptoms. These included severe fatigue, brain fog, shortness of breath, memory loss, fibromyalgia, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, depression and nausea. The broad range of symptoms reflects the variety of COVID-19 symptoms too, as the virus can attack multiple organs, which makes it even harder to define it as a single condition.

In October 2021, the World Health Organization defined Long COVID as a “post COVID-19 condition” that occurs if symptoms persist three months after infection and for which there is no alternative diagnosis, although this still varies from the way other health agencies have defined it. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines the condition as starting four weeks or more after first infection, for instance, and this dissonance makes it hard for researchers to produce comparable studies.

Difficulty in diagnosing the condition has meant that some patients have been dismissed as having a psychomatic condition, especially given the overlap with ME/chronic fatigue syndrome-type symptoms of debilitating exhaustion. However, evidence is starting to emerge of some explanations for exercise-related fatigue with Long COVID, for example.

In a study published this January, patients with Long COVID who exercised on a stationary bicycle and quickly became out of breath seemed to have issues with their blood circulation, preventing oxygen from being delivered efficiently to their muscles. Another study suggested that Long Covid patients experience damage to specific nerve fibreinvolved in the functioning of organs and blood vessels.

Persistent fatigue and cognitive impairment could be explained by damage to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, cerebral microvascular injury or damage to the prefrontal cortex that has now been documented in COVID-19 patients.

Have you read?

Another theory is that Long COVID symptoms can result from damage to the vagus nerve, which runs the length of the spine and connects the brain to the torso, heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles, and has a role in heart rate, swallowing, and moving food through our intestines. In research to be presented this April at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Lisbon, Portugal, a team led by researchers in Spain found that two-thirds of Long COVID patients they studied had at least one symptom of vagus nerve damage.

Understanding risk factors

Women aged between 40 and 60 have appeared to be at a higher risk of developing Long COVID, sometimes outnumbering men four to one. Although this reflects a gender skew in other post-infectious syndromes such as chronic fatigue syndrome, there is little data to explain this. Women are more likely to seek healthcare, and therefore report symptoms, than men, which could explain the skew. It could also be a bias in the immune response to the virus.

In addition to gender, earlier this year researchers publishing in the journal Cell described four factors that could increase the risk of Long COVID, discovered by following 200 patients for around three months after diagnosis.

The risk factors are: a high quantity of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the blood early in infection which indicates a high viral load; reactivation of infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV); autoantibodies, or immune molecules that target the body's own proteins; and a pre-existing diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the most common form of diabetes, which also is a risk factor for developing COVID-19.

As these factors can be identified at the time of infection, screening for them might prevent COVID-19 rolling over into Long COVID. Given that we are still in the early stages of research into this condition, having better clinical algorithms for identification, diagnostic tests is crucial, as is more research in general.

Lowering the chance of getting it

So far it seems that even when vaccinated people develop breakthrough infections, the vaccines protect against developing Long COVID. A UK study in The Lancet, analysing data from the COVID Symptom Study app, showed that the risk of developing long COVID (defined in this study as symptoms lasting 28 days or more) was 50% lower in those who were double vaccinated.

Research from Israel (though as yet not peer-reviewed) found that symptoms of Long COVID such as fatigue, weakness and muscle pain were reduced by between 54 – 68% in people who had been infected after being vaccinated.

A concern is that children and teenagers have not been adequately studied in Long COVID research, but with cases of COVID-19 rising in children in some parts of the world, this research is becoming ever more necessary.

There is good evidence from the Children & Young People with Long Covid (CLoCk) study by researchers at the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health. The study, published this week, studied nearly 7,000 children in the UK aged 11 to 17 years and indicated that around 14% of children and young people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 may have symptoms linked to the virus 15 weeks later. This suggests that in the UK alone, tens of thousands of children might have undiagnosed Long COVID.

Given the sheer number of adults and children who are affected in varied ways through Long COVID, more research is clearly needed, although the nature of Long COVID means that more time is likely to be needed to unravel the condition fully.