Maria Bottazzi: the scientist creating a vaccine for the world

The co-director of the team behind the new Corbevax vaccine set out to make a COVID-19 vaccine that would be low-cost, patent-free and perfectly suited to lower-income countries.

- 8 March 2022

- 8 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Follow along: #InternationalWomensDay

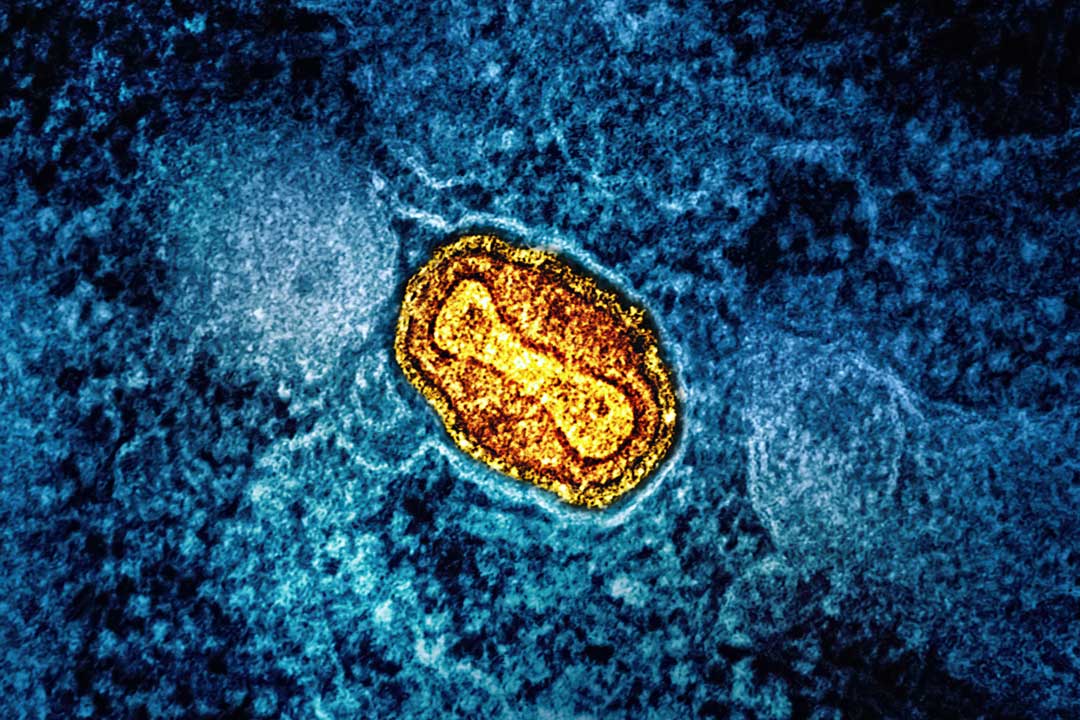

For most people, the COVID-19 pandemic came out of the blue, but not for Maria Elena Bottazzi. She had been predicting an event like this for years; her team had even spent the past decade developing vaccines against the coronaviruses that cause SARS and MERS.

Approximately a year before news of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan broke, Bottazzi’s team had applied for a grant to develop a pan-coronavirus vaccine – one that would not only protect against existing human coronaviruses, but also others that might emerge in the future.

Their proposal was roundly rejected: “The feedback was basically ‘there’s no innovation here; it is boring; this is not a priority that we need to focus on at this point’,” Bottazzi said.

“At the beginning, everybody wanted speed, everyone thought they might be able to contain this disease by putting a little Band Aid on it. We lost sight of the fact that, if we didn’t protect globally and equitably, we would eventually be impacted ourselves.”

Once the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and it became clear that a SARS-like coronavirus was to blame, they proposed re-engineering their existing SARS vaccine prototype to target SARS-CoV-2. This too, fell largely on deaf ears.

In late December, this re-engineered vaccine, co-developed with Biological E, Ltd. and named Corbevax, received emergency authorisation for use in India. Combined with the fact that it only requires refrigeration and is based on an existing highly scalable vaccine technology that manufacturers are already familiar with, it is being hailed as a vaccine for the world that could help close the COVID-19 vaccination gap between rich and poor countries.

Bottazzi has even been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize, alongside her long-term collaborator Dr Peter Hotez. Yet Corbevax and vaccines like it might have been available sooner, had wealthy donors paid more attention to the technologies underpinning them from the outset.

Corbevax is a protein-based vaccine, similar to those already used to immunise people against influenza, Hepatitis B, pertussis (whooping cough), and meningococcal disease. This makes it particularly attractive to low- and middle-income countries. Such vaccines don’t require ultra-cold storage, meaning they can be kept and transported in standard vaccine refrigerators and cool boxes, they remain stable for long periods of time, meaning less wastage due to short expiry dates, and because they’re based on a tried-and-tested technology, vaccine manufacturers don’t have to learn how to produce them from scratch.

“We also knew that they would be low cost, and that the reagents, including the formulations, would be accessible and could be made in bucket loads,” Bottazzi said.

“More importantly, I think we had a mindset of who would be the consumer, and what they would be willing to accept – so having that precedent of safety, including paediatric safety, and that precedent that these vaccines had worked in other instances, was important.”

The daughter of a Honduran diplomat, Bottazzi was born in Italy and moved back to Honduras at age eight. She went on to train as a microbiologist at the National Autonomous University of Honduras in Tegucigalpa. She relocated to the US to complete her doctoral training in 1995, and currently co-manages the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development alongside Hotez, and is a professor of paediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College in Houston.

Her commitment to empowering partners in poorer countries to protect their populations’ health is partly driven by the mantra that no one is protected until everyone is protected, but it is also powered by a desire to give back a little of what her home country has given her.

This includes a can-do mindset, bent on trying to achieve more with less. “In countries such as Honduras, we are quite resilient to being hit by adversity at all levels, but we always look to find solutions that don’t require a lot of investment, and are sustainable – so we often come up with some really creative ways of how to advance research,” she said.

“I remember during my training in the microbiology laboratory, we always had very little money, with very audacious goals, and so we had to reuse or repurpose things to achieve them.”

This mindset wasn’t necessarily shared by most of those allocating funding to COVID-19 vaccine development at the start of the pandemic. Rather than prioritising older vaccine technologies, such as protein-subunit and whole virus vaccines, mRNA and viral vector vaccines attracted the lion’s share of the funding at a global level.

Bottazzi believes this was a mistake. Although these technologies have proved highly effective at preventing severe disease in Western countries, limitations in their manufacturing and supply could have been predicted from the outset.

That’s not to say there should have been no investment in mRNA or viral vector vaccines. “The problem is that protein-based vaccine approaches received zero interest,” Bottazzi said. “This focus on the newer technologies has left a lot of people and countries behind, and that has provided the brewing ground of how this virus was able to mutate and evolve.

“At the beginning, everybody wanted speed, everyone thought they might be able to contain this disease by putting a little Band Aid on it. We lost sight of the fact that, if we didn’t protect globally and equitably, we would eventually be impacted ourselves – as we’re now seeing the effect with all these surges in infection.”

This is not simply a case of sour grapes. The Center for Vaccine Development has its own mRNA vaccine development programme. "We love innovation. But we knew that whatever technology, whatever solutions we needed to advance, their appropriateness for global health should be taken into consideration,” Bottazzi said.

“We were very worried that, because of the cost, because of the ramping-up of know-how and the challenges of bringing new technologies into the mix whilst trying to address an emergency, that we needed to find something that could be very easily transferable, meaning countries wouldn’t be reliant on others to produce vaccine.”

Her team continued to look for funding for their repurposed vaccine. First to commit were the non-profit health organisations PATH and the Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI) – now known as the Access to Advanced Health Institute (AAHI). Tito’s Homemade Vodka also contributed $ 1 million, through its philanthropic arm, alongside a cadre of other philanthropic institutions and individuals.

Meanwhile their proposal attracted the attention of one of India’s largest vaccine makers, Biological E. Limited (BioE), which had the aspiration of developing an indigenous COVID-19 vaccine and transitioning from a follow-on company to become a first-rate innovator. But they also struggled to obtain the funding to develop a protein-based COVID-19 vaccine.

Bottazzi’s wasn’t the only group working on such a vaccine, but they were unusual in their commitment to developing one patent-free, meaning any manufacturer with experience of this technology could potentially recreate it. If successful, this would reduce countries’ reliance on the Global North to manufacture and supply it.

“It is always these high-income countries dictating what is needed for the low-income countries, from clinical design, through to product development and regulation,” said Bottazzi. “Our aspiration is that we really need to break this paradigm and have them take ownership of these things.

“That’s why when we gave that technology to BioE, Corbevax is BioE’s vaccine – it is not Baylor’s or Texas Children’s vaccine. Of course, they were powered by our technology, but they co-developed it with us, and it is India's vaccine – for the world, hopefully.”

Eventually, the vaccine entered two large phase three clinical trials in India, which found it to be safe, well-tolerated, and more than 90% effective at preventing symptomatic infections associated with the original COVID-19 variant, and more than 80% effective against the Delta variant.

So far, the Indian government has ordered 300 million doses. On 28 December 2021, it approved the vaccine for emergency use in adults. On 21 February, it extended this to 12- to 18-year-olds. Further authorisations in other developing countries are expected to follow, and BioE has announced plans to produce more than one billion doses during 2022.

Bottazzi is already collaborating with manufacturers in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Africa, about recreating the vaccine for themselves. “Right now, we're just brewing and boiling with excitement,” she said.

She hopes their decision to share the technology underpinning Corbevax will inspire a new approach to vaccine development – one which may also benefit neglected tropical diseases. Besides COVID-19, a major focus of the Texas Children’s centre is the development and testing of vaccines against human hookworm, intestinal schistosomiasis and Chagas disease – candidates for hookworm and schistosomiasis are currently in human trials, and their Chagas vaccine is in the process of being manufactured.

“I think it is already starting to open up the eyes of other academic institutions that would like to expand their research and involvement in this type of work,” said Bottazzi.

She is also hopeful that it will inspire vaccine manufacturers and governments in low- and middle-income countries to invest in the workforce education and infrastructure to develop vaccines for themselves. Doing so would have long-term benefits beyond COVID-19. “Health should be at the centre of a country’s security. It is measured by more work, and therefore less conflict, and more economic returns.”

More from Linda Geddes

Recommended for you