Faster with wings: Ghana’s immunisation rates soar in Zipline-served districts

Drone delivery of vaccines has helped immunisation programmes in remote parts of Ghana’s Western North region bounce back faster than average from the pandemic’s impact, new research says. VaccinesWork visited the Zipline regional hub to find out more.

- 15 June 2023

- 9 min read

- by Nanama Boatemaa Acheampong

Asawinso Health Centre, in Ghana's forested, agrarian Western North region, is modest: four squeezed rooms and a veranda, the entire structure yearning for a fresh coat of paint.

On the veranda, which accommodates a table and two chairs, a vaccination clinic is proceeding at a practised, comfortable rhythm. A nurse in a smart green-and-white uniform draws up an injection and deftly administers it to a baby cradled in its mother's arms. Nearby, about a dozen more women and their infants wait for their turn, on rows of weathered benches sheltered beneath a tin roof.

“Gavi's partnership with Zipline, which launched in Ghana in 2019, has proven to be a stellar example of how technology-powered innovation finds its purpose in fortifying the very foundation of primary healthcare systems.”

– Bertrand Pedersen, senior manager for Private Sector Partnerships and Innovation at Gavi

The health centre serves a community of 26,531 individuals, most of them from cocoa-farming families, says Richard Junior Mensah, Senior Community Health Nurse. The vaccine clinic is open daily, and most Sundays, the health workers bring cold boxes stocked with vaccine doses out to churches.

That consistency is striking, given the logistical challenges facing this region. The road from Sefwi Wiawso, just 43km away, is uninviting even in good weather: janky, meandering, untarred, soil-red. It typically takes locals five hours to travel from Asawinso to Kumasi, the region's closest and biggest city.

"We live in a very difficult area when it comes to travel. Especially when it rains, how vaccines will get to facilities is a major challenge," remarked Osei Sekyi, the regional director for Ghana's Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI). "Each district has its own unique tale, as they all have remote and difficult-to-reach communities."

Access hurdles like these can choke supply chains, halting preventive health care in its tracks. But Asawinso and other health clinics in this region have found a solution.

Credit: Nipah Dennis

In the early afternoon, that solution – red-and-white, winged and not much bigger than a child's kite – appears in the sky above Asawinso Senior High School's football field. It's a Zipline medical delivery drone, and without pausing on its flight path, it drops its cargo. A red box equipped with a tiny parachute gusts down onto a grassless portion of the sports pitch. Nurse Richard retrieves his package, inspects its contents, and turns to make his way back towards the health facility.

"It's that simple," he says with a smile. "Mothers feel at ease knowing they won't endure hours of waiting. The vaccines arrive quickly, we care for their children, and they can quickly resume their daily routines."

Flying bounce-back

Enabling access to vaccination has never been more vital. Around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic forced an unprecedented drop-off in immunisation rates. Ghana was no exception: between 2019 and 2020, coverage with the third dose of diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus-containing vaccine (DTP3) plunged from 99% to 97%, leaving some 32,000 additional Ghanaian children vulnerable to vaccine-preventable illnesses.

Since then, Ghana's health services have been making up lost ground across the country.

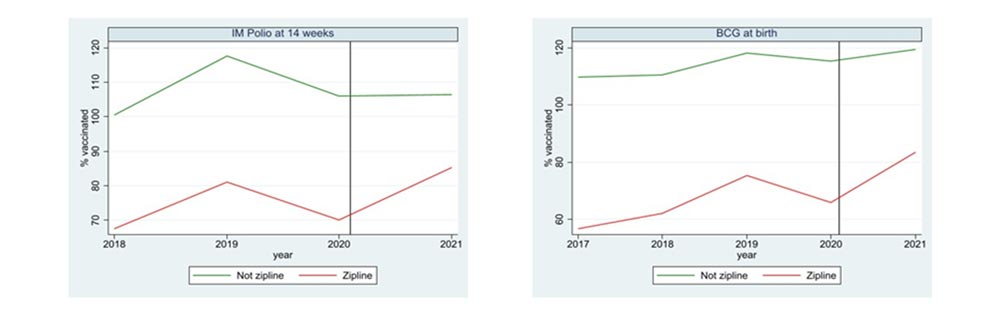

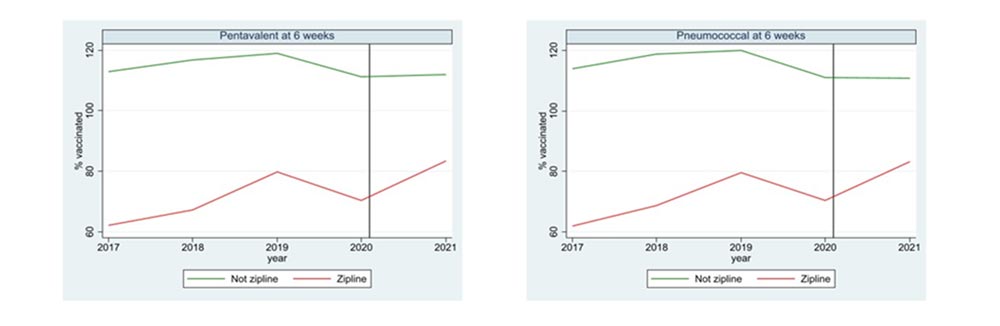

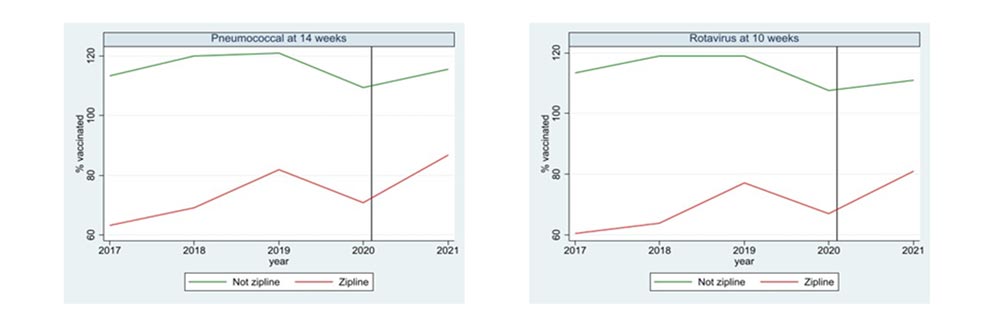

Compellingly, new research looking at clinics in Western North between 2017 and 2021 suggests the post-pandemic bounce-back has been quicker in those portions of the region where Zipline's drones helped to keep vaccine clinics ticking over, as compared to areas reliant on traditional supply chains.

The study, currently in pre-print, finds distinct immunisation coverage drop-offs at both Zipline and non-Zipline clinics in 2020. But though Zipline-served clinics typically show much lower coverage baselines in than non-Zipline counterparts – Zipline drones, after all, were brought in to serve underserved areas – the climb in coverage rates following the 2020 plunge is strikingly steeper in drone-served zones, exceeding 2019 coverage rates, in many clinics' cases, by the measurement end-point in 2021.

"We saw a reduction of over 40% [44%] in missed opportunities to vaccinate children in Zipline-served Western North facilities [relative to facilities in the same region that were not served by the medical drones]. This means that a lot of children had access to the vaccines they needed because Zipline made them available. That, to me, is one of the most important findings," the paper's lead author, Dr Pedro Kremer, Zipline's head of research, told VaccinesWork.

Moreover, the average duration of the last stockout, measured in days, was 30% lower in Zipline-served facilities compared to facilities not served by Zipline. For the paper's authors, the indication is that drone-delivery helped shore up Ghana Health System resilience – even amid the disruptions imposed by the pandemic.

It's that simple

Zipline's Western North hub – one of six such hubs in Ghana – is located at Sefwi Wiawso and serves 415 facilities, across 19 districts. For 217 of these facilities, Zipline is the sole distributor of vaccines.

On a blue-skied afternoon in mid-May, VaccinesWork visited Sefwi Wiawso to meet the team delivering life-saving vaccines by air to isolated communities.

"What we do here at Zipline is very important," said Lovelyn Keteku, the flight operations lead at the Sefwi-Wiawso base. "The big aspect for me is the whole magic with customers getting the product when they need it. With every package we send, we have it in mind that we're saving someone's life."

The drones are fast enough that vaccines can be called for and delivered all within an afternoon's clinic session. The journey from Sefwi-Wiawso to Asawinso Health Centre, for instance, takes about an hour at ground level in good weather. By drone it's a serene 23 minutes. The furthest-away clinics take the drones an average of 55 minutes. By road, the same trip is an ordeal: "You're looking at four hours and beyond," said Keteku. "But that's in an ideal situation where the road network is good. If we have bad weather conditions and stuff, we could be looking at five hours just to get to those facilities."

Have you read?

Historically, it wasn't only transportation logistics that posed a challenge to the local immunisation programme. "When we started as a region, we had no cold rooms, but Zipline came to our rescue," said regional EPI chief Osei Sekyi. "Initially, each district would have to move to Takoradi, our mother region, to pick up their vaccines on a monthly basis. When Zipline came in, we made a plan with them where at the end of each month, they would pick up the stock for all the districts and store them at their end. Then when it is time for vaccination sessions, Zipline would distribute them." The cold chain is strengthened, in other words, even as health centres come under reduced pressure to maintain fridges under tricky conditions.

Credit: Nipah Dennis

Since then, the logistical processes have come ever closer to "customer" – health centres like Asawinso. Kennedy Preprah, who has worked with Zipline for seven months, and works at the Raven's Nest, Zipline's call centre, explains, "We are the interface between Zipline and its customers. Customers place orders through various channels, including WhatsApp, voice calls, and text messages, and the orders come in various forms: resupply requests, emergency requests, or scheduled orders." The aim is to launch the laden drone within ten minutes. "When the package is five minutes away, we tell the customer so they can clear the drop zone and be on standby. Once the package delivers, we send another message to say it has been delivered, and we ask the customer to inspect it and report back to us within 30 minutes whether there are any issues."

With a top speed of 128km per hour and a range of up to 160km, Zipline drones' navigation systems allow them to autonomously avoid obstacles and make pinpoint deliveries. In cases of extreme weather or very bad wind, the drones are intelligent enough to signal that they can't fly.

They are also hardy. "Our drones are made up of four replaceable units," said Keteku. "If a particular unit is down, we're able to replace it quickly with another one so we don't delay the customer," she added.

Futuristic delivery, real-time effects

On the ground, the effect of all that airborne technology is both prosaic and profound. Reliable, rapid delivery of vaccines means health workers can make real-time interventions that would otherwise need to be deferred or ruled out.

"At the healthcare facilities, you'll hear a lot of success stories," Osei Sekyi said. "There was a situation where a two-year-old child was brought to the clinic by his mother, and it was discovered that he hadn't yet received a single vaccine. They had been living on a cocoa farm and had just come to stay in the community. When you meet a child like this, you can't allow them to leave without serving them. At the time, we didn't have any vaccines in stock, but Zipline normally supplies us in emergency situations, so we made a request. Zipline delivered, and that child took the vaccines he was due before he and his mother left. That was a very nice opportunity to reach out to a child who had missed two good years of vaccines. That gave the staff a lot of joy."

Credit: Nipah Dennis

"As a mother myself, it makes me happy to know that we can walk into any health facility and be assured that through Zipline, vaccines can be made readily available so my daughter can be protected," said Mabel Sekyere, who, as Zipline's Community Lead, works on engaging with social institutions, like educational facilities, to raise awareness of routine immunisation.

"Gavi's partnership with Zipline, which launched in Ghana in 2019, has proven to be a stellar example of how technology-powered innovation finds its purpose in fortifying the very foundation of primary healthcare systems," said Bertrand Pedersen, senior manager for Private Sector Partnerships and Innovation at Gavi. "Amid the adverse conditions of the pandemic, the resilience showed by Zipline and Ghana instils a sense of optimism for the future of immunisation in the country."

Next chapters

"I've never felt that my work was as impactful as it is now," said Zipline's Dr Kremer, who has previously worked as a family physician, in policy for the Argentinian Ministry of Health, at WHO and at several NGOs.

His findings in the new paper begin to substantiate his instincts. But they also encourage further investigation.

"I think our next chapter is to put all the data we've gathered together and incorporate our findings into economic evaluations, because it's not just that Zipline's work is impactful and meaningful, it is also extremely cost-effective from an individual and societal perspective," he explained. "When you see our operations, one of the things that comes to mind is that it must be super expensive. Yes, it's not cheap, but if you were to monetise the costs of not having vaccines in place, then Zipline is extremely inexpensive."

And for 25-year-old Theresa Appiah, who arrived at Asawinso Health Centre with her nine-month-old son, due for his MR vaccination, or for 33-year-old Doris Sawuri, queuing on the bench at the facility with her seven-week-old infant, the value of reliable immunisation is bigger than dollars and cents, or, for that matter, of cedi and pesewas.

"Every time I come to the vaccine clinic, my son gets his injections. I have never been told to come back another day," said Appiah. "I am grateful to the health workers who show me how to keep my son healthy."

More from Nanama Boatemaa Acheampong

Recommended for you