COVID-19 infection linked to high risk of blood clots for months afterwards

Scientists have identified a 33-fold increase in the risk of potentially fatal clots in the lungs, and a five-fold increase in the risk of deep vein thrombosis in the 30 days after catching COVID-19.

- 8 April 2022

- 5 min read

- by Linda Geddes

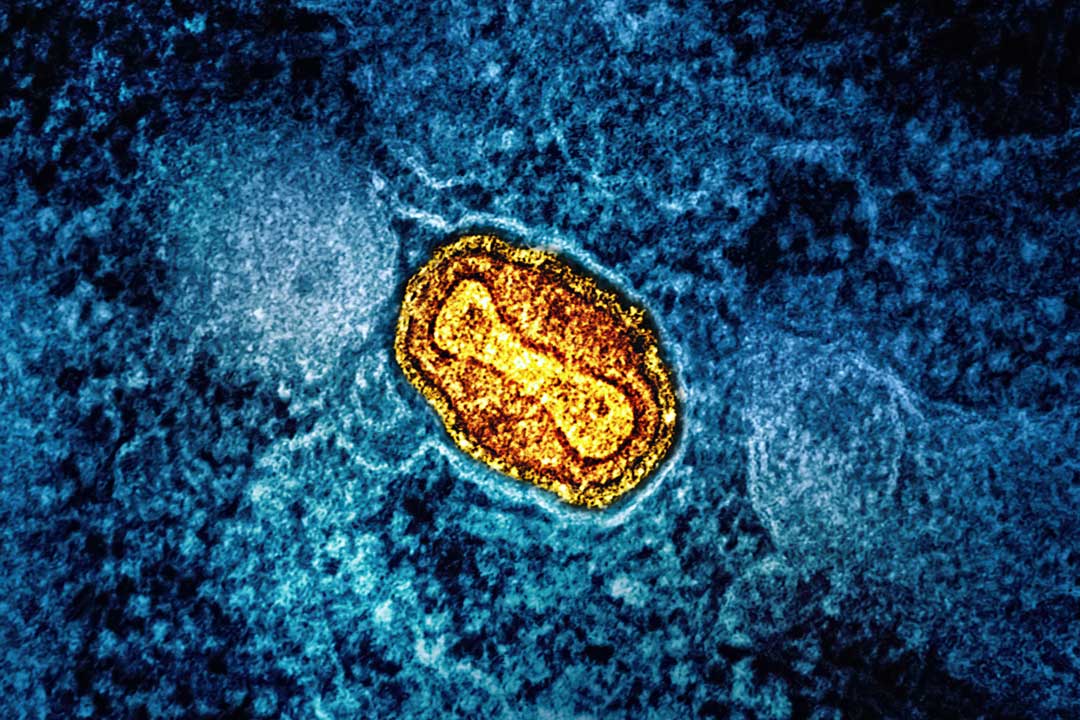

Blood clots have been an ongoing source of discussion during the COVID-19 pandemic: both in terms of the risks associated with catching SARS-CoV-2 and getting vaccinated against it. Now, a study of more than five million people in Sweden has identified an enormously elevated risk of potentially fatal blood clots in the lungs (pulmonary embolism), as well as an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and bleeding in the weeks and months after catching COVID-19.

COVID-19 infection was associated with a 33-fold increase in the risk of pulmonary embolism, a five-fold increase in the risk of DVT and an almost two-fold increase in the risk of bleeding in the following 30 days.

Although the study didn’t investigate clots associated with vaccines, evidence from other studies has suggested that the risk of these is significantly lower, emphasising the importance of getting vaccinated against COVID-19.

Importantly, even people with mild COVID-19 were found to be at increased risk of blood clots for months afterwards.

Swedish health records

Although various studies have found that COVID-19 increases the risk of serious blood clots (known as venous thrombo-embolism), it was less clear how long this risk persisted, and whether mild infections also increased people’s risk. Also unclear was whether the risk changed during different waves of the pandemic, and the impact of infection on the risk of major bleeding.

To investigate, Anne-Marie Fors Connolly and colleagues at Umeå University in Sweden used data from Swedish health registries to assess the risk of DVT, pulmonary embolism and major bleeding (e.g. a burst blood vessel in the brain, or gastro-intestinal bleeding) in more than one million people with confirmed COVID-19 infections and more than four million uninfected individuals.

Elevated risk

Their results, published in the British Medical Journal, suggested that COVID-19 infection was associated with a 33-fold increase in the risk of pulmonary embolism, a five-fold increase in the risk of DVT and an almost two-fold increase in the risk of bleeding in the following 30 days.

Even those with mild COVID-19 had a three-fold increased risk of DVT and a seven-fold increased risk of pulmonary embolism, although they were not at increased risk of bleeding.

In absolute terms, this meant that a first DVT occurred in 401 patients with COVID-19 and 267 control patients. A first pulmonary embolism event occurred in 1,761 patients with COVID-19 and 171 control patients, and a first bleeding event occurred in 1,002 patients with COVID-19 and 1,292 control patients.

These risks remained significantly elevated for three months after infection for DVT, six months for pulmonary embolism, and two months for serious bleeding.

Connolly said: “Pulmonary embolism can be fatal, so it is important to be aware [of this risk]. If you suddenly find yourself short of breath, and it doesn’t pass, [and] you’ve been infected with the coronavirus, then it might be an idea to seek help, because we find this increased risk for up to six months.”

Have you read?

Mild infection

Although those with more severe illness were at greatest risk, even those with mild COVID-19 had a three-fold increased risk of DVT and a seven-fold increased risk of pulmonary embolism, although they were not at increased risk of bleeding.

Risks also appeared to be higher during the first pandemic wave compared with the second and third waves (the study only analysed those infected before 25 May 2021), which Connolly said could be explained by improvements in treatment and vaccine coverage in older patients after the first wave.

Vaccine-related clots

The study also helps to put the very small increased risk of blood clots associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine into context.

“While the risk of thromboembolic events is increased after vaccination, the magnitude of risk remains smaller and persists for a shorter period that that associated with infection,” wrote Dr Frederick Ho, a lecturer in public health at the University of Glasgow, in an accompanying editorial.

For instance, a review by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) last year identified 79 reported clotting events occurring in the UK up to 31 March 2021. All occurred after a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine. During the same time period, 20.2 million doses of the vaccine had been administered, suggesting that the overall risk of blood clots was approximately four people in a million who received the vaccine.

Of these clots, 44 occurred in the veins draining blood from the brain (which, like pulmonary embolism, can be fatal), and 35 were clots in other major veins.

Another recently published study that analysed electronic health records from 46 million adults in England between December 2020 and March 2021 found that an extra one to three people per million experienced one of these rare brain clots after receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine, and that there was no evidence of them being associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Published alongside it was additonal data from England, Scotland and Wales collected up until the end of June 2021. It found a two-fold increase in the risk of these extremely rare clots among people who received the AstraZeneca vaccine, equivalent to an extra 0.25 cases per million people.

These risks are small, compared to the risk of pulmonary embolism associated with infection, which can also be fatal.

Other benefits

Of course, clots aren’t the only thing to consider. COVID-19 can also cause short- and long-term lung damage, while recent research suggested survivors are at increased risk of long-term heart problems. Then there’s Long Covid, which vaccination also helps to protect against.

“I would definitely recommend vaccines rather than getting infected,” Connolly said.