Pandemic Culture: The “Bangalore Banksy”: Art Against the Darkness

The Bengaluru street artist Baadal Nanjundaswamy is well-loved for his public-spirited art interventions. Lockdown managed to quieten him for a moment – but only for a moment.

- 23 August 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

When lockdown began, Baadal Nanjundaswamy started drawing on paper: yet another sign of a world out of joint. “I love walls – I love the street. I want to express myself through the streets,” Nanjundaswamy says. The works on paper, which he photographed and uploaded to social media, represented a meagre alternative for an artist whose landmark interventions had always been so essentially public: public-facing, public-spirited. In 2019, just before India’s space programme was set to launch its ill-fated second moon mission, Nanjundaswamy had staged a “moonwalk” on Bengaluru’s convincingly lunar, pitted roads, to call out their dangerous state of neglect. The project went viral. Within days, the city council had resurfaced the street in question.

“But still when I was painting I was shivering, because I had that fear: it is everywhere.”

There had been other similarly pointed, wry, but always distinctly affectionate civic protests: a massive pothole had become a magical frog-pond, complete with a frog-kissing princess (the pothole was soon fixed); an open manhole metamorphosed into the maw of Yamaraj, God of Death (it was soon covered); a broken storm drain was made over into a frustrated slice of luxury swimming pool. “I always feel like this – like, every artist should contribute something to society,” he told me. By the time he was 40, Nanjundaswamy was something of a Bengaluru institution. On his most recent birthday (his 42nd) a city newspaper congratulated him as “namma [our] own Banksy”.

But India’s lockdown, beginning in late March 2020, was uncompromising. Overnight, the streets became inhospitable, apparently forsaken: blanketed in dry leaves, patrolled by lathi-armed police. For weeks, Bengaluru’s Banksy made watercolours on paper, feeling wretched and impotent about the crisis hitting the country’s migrant labourers, whom the curfew had left suddenly homeless, jobless and hungry. “It was terrible, actually. We were never used to this kind of living,” Nanjundaswamy recalls. “There were many people doing good things. Helping society. Like giving food and groceries [to migrant workers]. As an artist, even I wanted to help.”

The severity of the lockdown lifted by degrees, but the city thrummed with anxious uncertainty. Cases were rising. One heard, now, of COVID-19 deaths in in one’s own neighbourhood, and not just in China, or Italy, or Delhi. Nanjundaswamy emerged from his bunker slowly. He wondered whether he, a tuberculosis survivor, was especially vulnerable to this new virus. He thought his lungs might crumple at a second challenge.

Have you read?

His first step outside, paintbrush in hand, was a small one: “in front of my house – I never painted like that, in front of my house,“ he says. It was a single, shiny, fleshy coronavirus, bright on the dark surface of the road. It looked startlingly 3D: tangible, kickable. It’s here, he was telling the head-shakers and the chin-maskers, it’s everywhere.

He began to edge further into public space. “Actually it was very difficult for me to paint. I’ll tell you how: because it was scary. It was too scary. I was going alone – I had to find walls, I had to carry that ladder, I had to paint alone. I was not eating anything, because I was scared,” he tells me. In the past, friends, assistants and bystanders had always been on hand to help – street-level, large-scale work like his is sociable by nature. Instead, morning to night, curfew’s end to curfew’s onset, he was solo, and working double-masked under an extra shawl: “But still when I was painting I was shivering, because I had that fear: it is everywhere.”

Clicking through Baadal’s back-catalogue of pandemic work on his Instagram, or on the pages of national newspapers where his murals of the last year and a half have frequently landed, I’ve been struck by the absence of darkness. Instead, my favourite Baadal pieces are often hearteningly, pop-culture-silly. Take his COVID-era Jack and Rose. Windswept at the prow of the Titanic (now sailing the breezeblock wall of a Bengaluru roadway), they are rapturous, in love, perhaps transgressive in their way - but masked and separated by a responsible “social distance”. Then there’s The Mask in a mask. Or Thanos, shilling for soap and water at a sweetly conventional brass tap: even the most terrible among us (Marvel supervillains) are apparently no match for the very least (viruses).

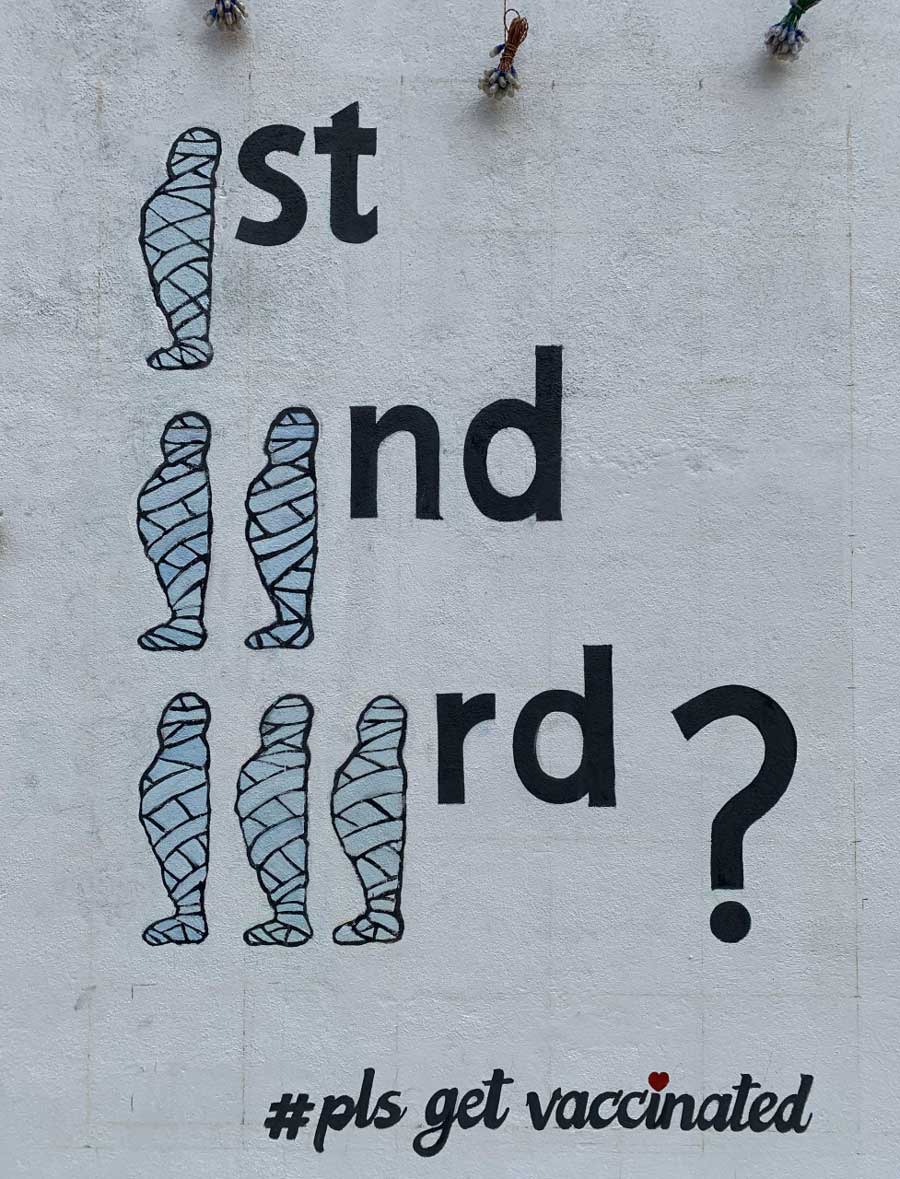

Nanjundaswamy says he means always to “bring a little smile,” spiced with “that sarcasm”. But after India’s terrible second wave, when crematoria were obliged to light funeral pyres at factory-line rates, and when the Ganges and its banks were suddenly crowded with the bodies of the uncounted dead, and when Indian online space became a desperate marketplace for medical oxygen, his tone changed. A mural he made in July visualised the scale of harm as a shrouded corpse: one for the first wave, two for the larger second wave, and a question-marked three for the possible third. “Pls get vaccinated,” the mural urged.

“It was very dark,” he says. “After the second wave, people started roaming freely. I just wanted to convey that – be careful. We don’t know when the third wave will attack us.” There was no push-back from the public for this sterner message, he says: “the truth was in there. It was like that. We all agree. So.”

Last week a new Baadal mural appeared on a long wall outside a petrol station in the Yelahanka neighbourhood. It was another sequence of three – this time a beautiful triptych of pandemic angels: a golden-winged medical worker, a haloed oxygen tank, and a nimbus-crowned vaccine syringe. “#getvaccinated”, Nanjundaswamy reiterated when he uploaded the new work to Instagram. Surely, Bengaluru knows by now that Baadal is always looking out for her best interests.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you